10 Zooming Past Institutional Boundaries to Tutor in a Community

Ryan Madan, Kristina Reardon, and Christina Santana

Worcester Community Writing Center

For many writing centers, the move to remote status during the pandemic was a temporary frustration alleviated by Zoom (and other meeting technologies), and the move back to in-person appointments was a return to the preferred. We—the writing center directors of three colleges in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 2020—witnessed the remarkable success of those technologies (in our own meetings and in the tutoring sessions at our respective campuses) while simultaneously strategizing an already-conceived project: a community writing center serving Worcester residents. From these experiences, we realized that a community writing center designed for our geographically complex city might best be built upon the increased access and flexibility that an online space provides. The pandemic, to our surprise, served as momentum for our pilot in the spring of 2021.

We embraced online, synchronous sessions as the preferred mode of engagement for the Worcester Community Writing Center (WCWC) in large part due to what we perceived as an opportunity to build on existing infrastructure. As the second largest city in New England, Worcester has nine colleges and universities (a half-dozen more in neighboring communities), many with some version of a writing center supporting enrolled students. In the community, a network of well-established organizations already support community members’ diverse goals of personal advancement and social change—many of which depend on writing. The WCWC was conceived of and piloted to offer a virtual bridge across these siloed experiences, connecting existing community support with three university writing centers through online synchronous appointments, creating a hub with the potential to build community by dissolving boundaries between colleges and the neighborhoods in which they are embedded.

In this article, we detail how forgoing the traditional brick and mortar of our own centers allowed us to activate several scholarly conversations to develop our model. We were moved first by Romeo García’s scholarship calling for center directors to think and act responsibly in the spirit of social justice and anti-racist work. The WCWC was designed to meet the needs of adult community members who might otherwise have trouble accessing or attending in-person sessions while also allowing traditional college tutors/students, who otherwise may insulate themselves in the cocoon of campus life, to engage with community members, witness the real rhetorical exigencies of social justice projects, and be part of extending these projects through the feedback they provide.

Our model was also informed by conversations around community-engaged writing centers, which explore how writing centers can use their values to inform community collaborations and use what Mark Latta calls a “fluid and adaptable” position “to hear and respond to the needs of their distinct communities” (2). The WCWC was designed to find itself more fully through its engagement with participants: student tutors, community partners, and our interactions as directors. We envisioned the WCWC as aligned with online writing centers uniquely trained to carry out the work the way Dan Gallagher and Aimee Maxfield describe.

From Plans to Reality

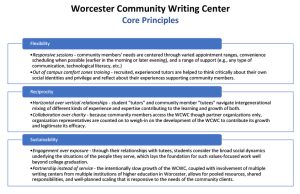

We spent considerable time during the fall of 2020 researching community-engaged writing, developing a shared vision and guiding ethos, determining what training student tutors might need, choosing an inaugural community partner, building a website, and establishing a research plan. The field of community writing/engagement and literacy recommends that the development and maintenance of partnerships with community members and organizations be characterized by flexibility, reciprocity, and when possible, sustainability. Accordingly, the work of Tiffany Rousculp and Allan Brizzee and Jaclyn Wells deeply informed our model.

Tutor Training for Digital Community Engagement

Six writing tutors, two selected from and paid through their respective institutions, were involved with the program. We offered a two-hour training so tutors could learn about logistics, and more importantly, could be oriented to the dynamics of engaging with community members and encountering cultural, racial, and socio-economic difference at levels they do not encounter working with peers; all tutors represented a range of socioeconomic backgrounds, five of the six were white and one was Black. We drew from Rousculp and Tania Mitchell’s work on developing rhetorics of respect in community writing and preparing students for service learning to present a training with written and oral reflection opportunities that pushed tutors to consider their motivations for working with writers outside of the university context, interrogate their privilege, and avoid reinforcing cultural, social, racial, and economic barriers and hierarchical relationships. In particular, we wanted tutors to consider their own social identities—as in what does it mean to be who you are?—in connection to, and in contrast with, the adult learners they would encounter. We wanted them to authentically consider how they might embrace partnership and collaboration wherever possible and avoid intentionally entering into unequal or vertical relationships (see fig. 2 for comparisons of demographics between the three colleges and the city of Worcester).

To facilitate such work, which the directors understand as recursive and relational rather than fixed, tutors reflected on their privilege both during the training and throughout the pilot by responding to two questions at the end of each week: “In what ways did privilege show up where it might not during university tutoring sessions?” and “Can you point to moments when you showed and/or communicated with respect, flexibility, or awareness to writers you worked with?” These reflections provided space for tutors to self-assess and develop their learning over the course of their participation in the WCWC.

Community Partner On-Boarding

In surveying potential community partners for the pilot, we proceeded from a position of respect, goodwill, and sustainability in order to meet community members in the context of organizations they are already affiliated with and center partnerships with community organizations that might enable initial connections (Brizee and Wells; Rousculp). Accordingly, we leveraged an existing contact, a colleague involved with Worcester’s local branch of the Clemente Course in the Humanities, which is a program through Bard College that offers highly-motivated adult learners free, credit-bearing college-level seminars that explores topics like the “U.S. Citizenship and Its Intersections” or “Storytelling for Social Change.” Nationally, these courses engage a diverse population (roughly 40% African American, 25% Latino) and lower barriers to college enrollment for low income individuals (74% of Clemente students nationally make less than $30,000/year, and the majority make less than $10,000/year [“About the Clemente Course”]) by offering free childcare and transportation. As Bard College describes on its homepage, the coursework is transformative: “Our free college humanities courses empower students to further their education and careers, become effective advocates for themselves and their families, and engage actively in the cultural and political lives of their communities” (“The Clemente Course in the Humanities”).

The program goals were well-aligned with our pilot for several reasons. For the Worcester Clemente program coordinator, collaborating with us was an opportunity to increase their capacity to meet their own mission of fostering partnerships and developing collaborative resources. Also, since these courses are delivered outside of a conventional college infrastructure, additional writing support was welcome. Finally, participating writing tutors could leverage their past experience, since community members wrote academic essays and attended class online, having been provided laptops and wifi access from the program. While we knew that the conventionally academic context of Clemente courses would mean our tutors might have less exposure to community members’ “real world” texts and exigencies, we also saw this as a potential strength for our pilot. We could, in these early stages, focus on developing tutor training materials surrounding issues of privilege and difference without the distractions of preparing tutors to grapple with novel genres, and tutors could focus their reflective energies on those questions of relationality rather than anxieties about whether they “knew enough” to help.

At the beginning of our pilot, the Worcester Clemente community coordinator invited us to visit classes, shared assignment sheets and syllabi, and helped us reach out to students in the program. She also helped us distribute a survey to gauge student interest in the project. Eight students (just more than half of this Clemente cohort) responded. Availability was scattered across days and times, and responses to our question about goals yielded enthusiasm and openness. We settled on the most flexible model possible, where community members reached out to the WCWC to communicate their availability, which was shared with staff members who took appointments they could accommodate.

Students’ and Tutors’ Experiences

During the pilot from March to May 2021, Clemente writers were working on academic essays about citizenship. Although a total of ten hour-long and one thirty-minute session was booked, in the end eight sessions took place. Five Clemente students participated. Three of our six tutors held appointments. As we reflected on the semester, a few themes emerged. First, tutors noted that sessions often focused on reading—whether that was reading assigned material or engaging with the assignment prompt. Second, tutors talked through genres (like the annotated bibliography) and writing processes, using free-writing and examples from their own work to connect with students. Finally, all tutor reflections mentioned technological literacy as a site of privilege, noting that significant portions of each session were spent coaching community members on using advanced features of Zoom or Google docs to facilitate conversation.

Surveys with community members (four of five responded) revealed that they accessed the WCWC when they were planning their writing, and they saw this as valuable. One wrote that they appreciated the time and space for “processing my thoughts.” They appreciated the “multi-generational” resource and the fact that “they [the tutors] were comfortable with my questions.” And while tutors worried that technological literacies might have gotten in the way of tutoring, all survey respondents noted that they left the session with a clear plan to improve at least one thing about their writing. Further, all agreed that the session notes (tutor notes to clients after meetings, constructed as emails summarizing the details of the session and next steps) helped them when they continued to write or edit after the session was over. Two community members gave us permission to analyze their appointment records, and these examples illustrate community members’ differing goals. One focused entirely on the genre expectations of an annotated bibliography and MLA citation, with a clear outline for continued work and links to online resources. The tutor shared some of their own annotated bibliographies as a way to connect and to explain the form. Meanwhile, the other focused on developing an argument and spent a significant part of the session talking about a detailed metaphor. The tutor built a connection with the ideas in the writing by encouraging creativity and urging the writer not to worry about formatting in the first draft but rather to get ideas (like the metaphor) down on paper.

This sense of connection and community that students and tutees reported with one another helped us see that two of our primary goals–that community members have access to tutoring, and that students engage with community–were met in ways that felt meaningful to both constituencies. While the community members did focus on their writing for school-related genres–and so did not reach the real world exigencies of social justice projects as we envisioned for the service at scale–the work that was accomplished was not limited to school-related skills alone. As one tutor reflected in a post-semester interview: “The writing that tutees brought in for the WCWC: it was for a class but also related to things they wanted to improve in their day to day life as well.” This extended to a range of things, including English language use, but mostly technology. For example, when screen sharing on Zoom proved ineffective, this tutor spoke compellingly about showing the community member how to create a Google doc so they could edit together. The lessons from this session were as much about writing as they were navigating digital platforms. And tutors also perceived value in the opportunities to coach community members through screen sharing and collaborative editing on cloud-based platforms; one noted that even in a potential post-Zoom era, “being able to pass on some additional computer skills may be beneficial” in a range of contexts.

The sense of partnership and community were palpable in tutor reflections and community members’ surveys. As the third tutor noted, community members came in “with the mindset of we’re going to sort of work through this together.” This prompted them not only to share knowledge about academic writing genres and cloud-based editing technology, but to consider the points of view that community members spoke and wrote about for their assignments, which may have taken an academic form but dealt with citizenship—a topic with real-world exigency for a diverse cohort of adult learners straddling national, ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic worlds. The tutor reflected: “…Just being able to see someone else’s view, that opens up my own view. It makes me consider things that maybe I would never have considered, and so, in that sense it’s one of the biggest successes: when I can have those conversations and learn from their perspective on their project or their paper, whatever it may be.” We were heartened to read this comment since it illustrated the sort of reciprocity and relationship-building we had hoped would happen during sessions.

Moving Forward with Community

We knew from conversation with the Worcester Clemente community coordinator that the online, flexible model was desirable because it provided access to tutoring sessions at a range of times and places. With less travel time for tutors (overstretched from their school work and regular tutoring hours) and community members (attending night classes on top of their day jobs), an online approach respected the time of participants. Yet despite the affordances of online access, a deeper look at booking patterns, session notes, and reflections also revealed roadblocks.

One major roadblock came with scheduling. Email allowed community members to flexibly request times that work for them, but frequent rescheduling created long, confusing threads that may have been responsible for late arrivals or missed appointments on both sides. Some community members were hesitant to request certain times due to perceived impositions. For example, one declined a May appointment because he did not want to interrupt Mother’s Day. During busy periods, like midterms, we had to prompt tutors multiple times to respond to a request. And our central account needed close, but irregular, monitoring of appointment requests, rescheduling messages, and questions about logging into sessions as they began.

Another challenge came in reaching those who may not have time to meet, even online, or who may not be comfortable reaching out. We considered offering online asynchronous consultations, or holding a pop-up writing center before or after class in the Clemente space so that community members could meet tutors, book a future online session, or even stay for a session. We recognize that in future iterations of this project, wifi and computer access may need to be part of our planning in terms of outreach and access. And tutors also noted that they wanted to develop more experience in offering technology assistance with Zoom and Google docs specifically so they could, as one tutor suggested, provide clear guidance that community members could reference after sessions end.

We have learned to rephrase these challenges not as the best we can do to reproduce in-person tutoring under compromised circumstances, but rather as the best way to connect to the community.

While these lessons are on our mind as we plan the future of the WCWC, there is a more important insight that threads through our reflections on our pilot: the very roadblocks we try to skirt are themselves signs that we occupy the road with fellow community-engaged neighbors. This project reminds us that perceived roadblocks are signs that we are participating in a certain kind of collaborative work. We have learned to rephrase these challenges not as the best we can do to reproduce in-person tutoring under compromised circumstances, but rather as the best way to connect to the community. If we want tutors to grow through this process—to understand differently by virtue of their interaction—then we need to continually reframe frictions not as a side effect, but as a product of the work we do. These frictions are moments to confront discomfort produced by grappling with difference and acknowledging uneven power structures. The contact zones between community members and tutor are ones we could not, and would not want to, smooth away entirely.

Perhaps the above challenges can be reframed in the style of Mariolina Salvatori’s call for embracing difficulty as a sign of “incipient understanding”—an initial recognition that, if pursued, can lead to knowledge (200). We can see technological questions as problems that need ameliorating, or we can see them as sites to expose points of privilege through which tutors newly understand literacy and community. We can see the need for flexibility as an issue to manage away (what if we could find just the right physical site to set up shop? How do we advertise better?), or we can embrace that itinerancy is fundamental to working in community spaces where writing projects might proceed in fits and starts, filling in cracks around the edges of community members’ full and variable lives. The former mindset suggests that community writing and those who generate it are puzzles to be solved through administrative processes. The latter mindset suggests a return to the premise upon which we started this pilot: that tutors can benefit as much as writers by being part of that journey.

To see our pilot through this lens means valuing our eight sessions, a number that, in an era of writing center directorship focused so intently on cost efficiencies, may seem unremarkably modest. As we’ve shown above through our initial assessment with participants in the first pilot year, eight sessions was enough to make tutors feel that they both provided and benefited from powerful conversations with community members. It was enough for them to learn about each other and to excite our community partner. Even at a time when many university budgets were tapped and faculty were stretched thin, our model allowed our success rubric to look different; we felt energized enough to continue with this work. But just as in our teaching, our success rubric will need to change and grow with new contexts. In 2021-2022, we only had two requests for tutoring, and in 2022-2023, we had three requests and held two sessions. We speculate the shift to in-person instruction at both the Worcester Clemente site and local colleges rendered Zoom less enduringly salient than we first hoped. In this newest stage, we continue to focus on the value of tutors and community members interacting, even as we–like many other community organizations–are still grappling with ways to move forward post-Covid. We continue to assess whether and how an online space can help us maintain a sustainable presence in the community, while also allowing us to push back against neoliberal ways of conflating the value of our outreach with the quantity of sessions.

Moving Forward as Colleagues

The WCWC began as a community engagement project of three directors who sought community themselves. We had talked about bringing our writing centers together for years, but we never followed through. Who would host? How would we coordinate transportation for tutors? The questions were solvable but dissuasive enough to kick down the road. COVID forced us to embrace an approach that seemed another barrier in itself: meeting online as default. Months of meetings allowed us to formulate our early trajectory but might not have happened so regularly (or at all) if not for the convenience of Zoom, on which we continue to rely for collegial support and project management. We certainly wonder whether we would have arrived at our most important lessons if not for the ways that the pandemic had us Zooming into each other’s offices.

Material constraints shape the contours of what feels possible, not only for writers but also for us as we try to sustain an extra-institutional project. We recognize that in the distributed model of directorship on which our initiative depends, flexibility is a requirement. Indeed, two of us have changed institutions since our 2020-2021 pilot, both moving to nearby Amherst College. Yet we remain committed to working with the community and with each other as colleagues and co-directors. We remain in pilot mode by necessity as we continue to sort out what community will mean now that we are not all in Worcester, and what online access affords as in-person work becomes more normalized. As such, we are pursuing two threads as we move forward. Recent meetings with Clemente leadership have helped us understand that some other Massachusetts-based Clemente sites remain online even post-pandemic, while others, like Worcester, are back in person. We have plans to explore the pros and cons of online versus in-person tutoring by offering pop-up events with Worcester Clemente in spring 2023, as well as other Clemente sites later in 2023, to better understand how best to provide support when and where it is needed. We also maintain our ambitions to eventually onboard a few additional community partners in Worcester and Western Massachusetts alike (from sites where writers regularly gather, including the public library as well as refugee/immigrant support groups, English language programs, and creative writing circles).

Our pilot’s entry points have served as beginnings—invitations for faculty collaboration, cross-institutional work, longitudinal consistency, and interaction with the community. As we continue negotiating the future of our community-engaged writing model, we see the layers of cross-institutional and cross-sectional community as critically important sites of learning for directors, tutors, and community members alike.

Works Cited

“About the Clemente Course.” The Clemente Course in the Humanities. www.clementecourse.org/about. Accessed 24 August 2022.

Brizee, Allen, and Jaclyn M. Wells. Partners in Literacy: A Writing Center Model for Civic Engagement. Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

“The Clemente Course in the Humanities.” Clemente Course in the Humanities | Bard College, www.clemente.bard.edu. Accessed 24 August 2022.

Gallagher, Daniel, and Aimee Maxfield. “Learning Online to Tutor Online.” How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen Gabrielle Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/GallagherMaxfield.html.

García, Romeo. “Unmaking Gringo-Centers.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 36, no. 1, 2017, pp. 29-60, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44252637.

Latta, Mark, Helen Raica-Klotz, and Chris Giroux. “Guest Editors’ Introduction: Community Writing Centers: What Was, What Is, and What Potentially Can Be.” Community Literacy Journal, vol. 15, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1-6, https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/communityliteracy/vol15/iss1/2/.

Mitchell, Tania. “Traditional vs. Critical Service-Learning: Engaging the Literature to Differentiate Two Models.” Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, Spring 2008, pp. 50–65, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ831374.pdf.

Nichols, Amy McCleese, and Bronwyn T. Williams. “Centering Partnerships: A Case for Writing Centers as Sites of Community Engagement.” Community Literacy Journal, vol. 13, no. 2, 2019, pp. 88-106, https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1039&context=communityliteracy.

Rousculp, Tiffany. Rhetoric of Respect: Recognizing Change at a Community Writing Center. NCTE, 2014.

Salvatori, Mariolina Rizzi. “Reading Matters for Writing.” Intertexts: Reading Pedagogy in College Writing Classrooms, edited by Marguerite Helmers. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2003, pp. 195-218.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Elizabeth Bacon, Community Coordinator for Worcester’s Clemente Course in the Humanities, for her partnership, support, and encouragement. We would also like to thank the community members and tutors who participated in this study.

This study was supported by a Scholarship in Action seed grant from the J. D. Power Center for Liberal Arts in the World at the College of the Holy Cross, which funded research costs associated as well as wages for Holy Cross tutors. Special thanks to Associate Professor of History and Scholarship in Action Director Mary Conley.