9 How We Write Now: A Preliminary Study of the Culture of Writing on Campus during the Pandemic

Jack Friedman, Ryann Liljenstolpe, Dominique Morra, Alex Rodriguez, Andrea Scott, and Gabriel Scherman

Pitzer College

Writing centers are relationship-rich environments for learning. Decades of research has shown that peer-to-peer, student-to-staff, and student-faculty relationships are key to cultivating learning, belonging, and academic success on campuses, especially among first-generation and other minoritized students (Felten and Lambert 5). As the pandemic moved the educational experience online, the traditional infrastructure for such learning was ruptured, particularly on shuttered residential campuses. Housed at a small liberal arts college in Los Angeles County, a COVID-19 hot spot early in the pandemic, our writing center sought ways of reproducing the intimacy of the small college by fostering virtual connections among peers, particularly first- and second-year students. In Spring 2021, the writing center director taught a new course called “How We Write Now,” which put students in the role of researchers studying the changing culture of writing on campus amidst COVID-19. The course also helped to build community on campus. Students would develop relationships with each other and faculty through the high impact practice of research (e.g., Kuh) and the use of peer interviews and interactive learning. Under the director’s facilitation, students designed a research study, collecting writing artifacts and conducting one-hour interviews with their peers about what, how, and why they were writing during the pandemic.[1]

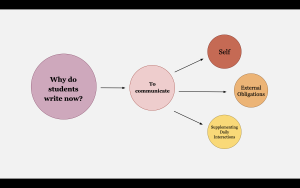

In what this article will now refer to as our study, we discovered that writing served as a consequential site for exploring identity, meaning, and value amidst the social isolation of the pandemic. The act of writing itself was also a task difficult for some to perform due to inequities and constraints exacerbated by COVID. And yet our research subjects, whom we will refer to hereafter as students, reported that writing became the primary means of communicating with faculty and peers outside of Zoom meetings, placing particular pressure on written expression as a medium. Students also shared stories of the multiple strategies they used to cultivate a writing voice in different contexts, often turning to journaling as a means of making sense of the world in the absence of social validation.

Our study doubles as a model for conducting student-led writing assessments on campuses in resource-constrained environments. The final product, a published article, posed a learning opportunity for student-researchers to engage with what scholars Paul Anderson et al. describe as “effective writing practices,” including staging writing as an “interactive process,” with multiple opportunities for feedback from peers and instructors, and engaging in tasks that are “meaning-making” with “clear expectations” (quoted in 206-7; see also Anderson et al. 5-6). This research project also provided a pathway for conducting student-led assessment at a moment when assessment of core competencies may have ground to a halt elsewhere on campus amidst the resource constraints of the pandemic and its aftermath. Writing centers, particularly those with access to course-based teaching, can be strong partners in institutional assessment by designing courses that empower students to research and ask the questions most pressing to them, which in turn can help shape the curriculum through the integration of such findings in faculty development workshops.

Methods

Since our research study doubles as a model for conducting collaborative, student-led assessment, we would like to first describe how our project came into being. Ten students in the seminar How We Write Now spent a remote semester working with the then director, the instructor of record, researching threshold concepts in writing studies and emerging debates in the field, such as antiracist writing assessment. As a group, the student researchers drafted and refined their research questions in conversation with these sources. The director served as a facilitator, grouping the questions and asking the students additional questions to help refine them. We then read research on methodologies and methods, including semi-structured interviews, to create our research instruments: a demographics survey and an interview script. After working backward from our research questions to draft and revise questions for semi-structured interviews, the director submitted a research proposal for approval from the campus’s institutional review board. Each of the student-researchers in the course then conducted a mock interview with a writing center consultant to reflect on and refine their interviewing skills. Since student-researchers in the course wanted to deepen their learning about one another, they decided that they would each interview each other as well. Students would then interview one other student of their choosing on campus. Students then used Zoom’s transcript feature to produce transcripts of the interviews that they edited to ensure the transcripts matched the students’ choice of words before writing one-page summaries of the interview themes, which they reviewed and revised in small groups. As the final project, students worked in small groups to each submit an abstract to a conference addressing a subquestion of our study. They also collaborated as a class to create a PowerPoint presentation on their core findings to share with the campus community.

In the summer, the Writing Center received $2,800 in internal funding to sponsor student-led assessment for the project. The student co-authors of this article voluntarily signed up for this opportunity and split the grant to work on this chapter. The director created an informal syllabus based on our six-weeks of summer funding, with students concluding the writing for submission in August 2021.

In designing the study, we drew purposefully from two methodologies. The first, a “writer-informed approach,” developed by Jeff Naftzinger, “gives the writers we study a role in collecting and selecting the data we analyze, in shaping our interviews, and, ultimately, in guiding the trajectory of our research and results” (81). In our study, the student co-authors were both study participants and researchers, interviewing each other and those outside our team with the goal of discovering where the field’s “scholarly assumptions and understandings diverge from those engaged in writing in their everyday lives” (81). Students and the student researchers speak here in their own voices in ways that center their own experiences as writers, which means their claims sometimes go against the grain of the field. Second, we drew from the methods and values of “rapid ethnographic assessment,” which Thurka Sangaramoorthy and Karen A. Kroeger describe as a “team-based, multi-method, relatively low-cost approach to data collection that relies on methods like interviews […] and brief surveys” to produce an understanding of the social factors that contribute to an emerging phenomenon, in this case writing amidst the pandemic (“In Current Climate”). The pragmatic approach of this methodology aligned well with the constraints of the pandemic.

Our data consisted of twenty-two semi-structured interviews with students, each of whom shared their experiences around three main themes intended to capture writing practices and values during the pandemic: what are you writing now, how are you writing now, and why are you writing now? Prior to the interview, each student was asked to complete a survey that captured demographic data such as race, ethnicity, gender identity, multilingualism, geographic homes, age, and major, and a list of the types of writing they have done frequently the past two weeks (Appendix). Participants were also asked to provide two writing samples of their choice. Twenty-one of the twenty-two students completed the survey and submission. Eleven of the video or audio-recorded interviews were conducted with students in the class, and eleven of the interviews were conducted with students outside of class. Since coding software could not be accessed affordably in the remote environment, each student created a summative page from each interview, capturing its themes and supporting quotes. Members of the research team reviewed several interviews in full and read the reports to identify patterns, or meta-themes, that informed our conclusions, revising as we wanted to maximize consistency to enhance the trustworthiness of our method (Lincoln and Guba).

As students began evaluating our data, they saw more interesting questions emerge. Questions about what students were writing soon gave way to conversations and questions about the definition of writing itself. Questions about how and why students were writing were linked to how students defined success for their writing and saw their writing reflective of their multiple identities and goals. We foreground these emerging themes before exploring their possible implications for teaching and learning.

Results

Given our small sample size, it is important to preface our results by saying that they cannot be generalized. We note, for example, that half of the study participants were white and none reported identifying as Black or Indigenous. As mentioned above, twenty-one of the twenty-two participants in this study completed the survey, so the demographic data reported is incomplete in the context of the twenty-two interviews conducted.

Table 1: Demographics

| Self-Identifying Demographic Categories (n=14) | Percentage | Number |

| Class year | ||

| First-Year | 42.8% | 9 |

| Sophomore | 38.1% | 8 |

| Junior | 19.1% | 4 |

| Race and Ethnicity | ||

| Black | 0% | 0 |

| Hispanic | 18.2% | 4 |

| Asian or Asian-American or Pacific Islander | 27.3% | 6 |

| Indigenous people | 0% | 0 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 50% | 11 |

| Prefer not to say | 4.6% | 1 |

| Gender Identity | ||

| Male | 28.6% | 6 |

| Female | 57.1% | 12 |

| Non-binary/Third gender | 4.8% | 1 |

| Prefer not to say | 9.5% | 2 |

| Speakers of English | ||

| Monolingual | 57.1% | 12 |

| Multilingual | 43.9% | 9 |

| First Generation | ||

| Yes | 33.3% | 7 |

| No | 66.7% | 14 |

| Prefer not to say | 0% | 0 |

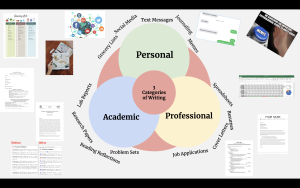

Using qualitative approaches allowed us to uncover counterstories and paradoxes in students’ experiences as writers. We found themes across stories that are the source of our findings. We were interested in three main questions related to the broader question: to what extent has writing changed or remained the same for students during the pandemic? The first question we sought to answer was, “What were students writing?” In order to answer this question, we found that students had to make a decision for themselves about what constituted writing. Interestingly, their definitions were expansive. Students listed text messages, emails, academic papers, notes, social media posts, class reflections, journaling, and poetry, among others, as being “kinds” of writing. Students listed text messages, emails, academic papers, notes, social media posts, class reflections, journaling, and poetry, among others, as being “kinds” of writing. In other words, they reported engaging in a wide variety of personal, professional, and academic writing in their everyday lives.

We noted with surprise and delight that students seemed to have an internal definition of writing capacious enough to encompass these multiple genres. Such thinking aligns with scholars of rhetoric and composition who define writing as the “work of making meaning for particular audiences and purposes” and as work made by writers who “are always connected to other people” (Roozen 17). Yet when we asked students what made these genres of writing examples of “writing,” they did not have a specific and unifying definition at their fingertips. Students often initially saw academic and personal writing as separate activities, as opposed to the field’s perception of them as social activities written for different audiences and purposes. When pressed to think through their responses, they often arrived at more nuanced definitions, however. When our research team debriefed about this, we noted the value of peer-led conversations about writing to prompt metacognition vis-à-vis the writing processes. Such conversations appear to give writers deeper insight into writing—and themselves as agentive writers.

Take coding in computer science. One researcher asked James, a student writer[2], “Is that writing?” When the computer science major was asked this question, he paused before responding, “Well, not exactly.” When pressed, it seemed that the key distinction between writing code and writing, say, for a politics class was the writer’s goal. Writing a paper on marginalized members of his community allowed James to better understand the hardships of community members’ everyday lives and later led him to draft a policy proposal to change California law. Behind this type of writing the student found a strong purpose: to convince others of a certain point of view. Like scholars in the field, James saw writing as the “work of making meaning for particular audiences and purposes” and, in his own writing, he came to see authorship as a position in which he was “always connected to other people.”

But James also encouraged the research team to think about forms of connection and response that are non-human. As he and his interviewer continued the discussion around the differences between coding and writing, James pointed out that coding and what he considered to be writing both sought to elicit an action or response. Yet the human element of writing became something that made writing ultimately feel more authentic to James. Persuading a human being to do something—to take action— is very different from, for example, convincing a machine to move, he concluded. Therefore, James ultimately wasn’t comfortable calling coding “writing.” Commanding a machine to conduct a Google search didn’t seem like writing to him because there was no conscious mind present to refute one’s arguments. The machine either understands the line of code, or it doesn’t. There’s no need for a machine to interpret or read between the lines. In this sense, James’ definition aligns with the field’s rather traditional schema, which sees writing as a social activity. It will be interesting to note if student perceptions of coding change in the wake of apps designed to interface with humans and machine-generated writing, which is growing more sophisticated by the day.

Whereas James thought his way into a more conventional definition of writing, other students started with more narrow definitions emphasizing its instrumental role. In her interview, Emily’s answer to “What do you consider to be writing?” was “Anything with a grade attached.” Indeed, Emily chose to submit samples of academic assignments she had written, a choice reflective of this definition. However, as the conversation continued, she offered the fact that she also writes outside of school and occasionally writes creative pieces in her journal, enlarging her definition as she spoke. Other students, like cognitive science major Zoe, excluded academic writing from their definition of writing, defining writing as work that is done on their own terms. “I don’t even consider school assignments [to be] writing because I do them because I have to do them,” Zoe emphasized.

That’s how I see it… like would I write a book review if I didn’t have to? Probably not. But would I do poetry if I didn’t have to? yeah I would…Would I do journaling if I didn’t have to? Yeah, I would still do it.

For Zoe, intrinsic motivation is the defining characteristic of “real” writing. She comes from a family of poets and writers who spoke out against past Iraqi regimes. Her sense of duty, both civic and artistic, influenced her perception of writing and its purpose. In the interview, she reported perceiving academic writing as a stepping stone, through a liberal arts education, to her future work. Zoe craved an audience beyond her professor. She needed to feel that her writing could generate community and change. If she perceived an assignment as falling outside of these parameters, it wasn’t “real” writing to her. She needed an agentive role in defining the purpose and audience of her work.

The above examples are illustrative of the range of definitions, implicit and explicit, that students hold of writing, even in the same conversation: writing as human, writing as transactional, writing as persuasive, writing as purposeful to one’s self or others. These different perceptions of writing reflect the diverse goals writers have for their work in college, goals that they often saw as linked to intersectional identities.

Another question in the interviews related to how students defined successful writing during the pandemic. As in pre-pandemic times, whether students considered a piece of writing successful or not was linked to their goals. These goals sometimes differed from their professors’, particularly when students were internally motivated. One student, Lennox, said;

So…for me…writing is not… if I get an A on a paper..like…I don’t consider that successful writing it’s more if…if I’m really proud about the piece that I’ve written.

Another student, Sam, stated:

When I come to new conclusions through my writing, or like I come to…new perspectives, or….new thoughts about something that I’d already been thinking about through writing, I think that’s when it’s probably the most successful seeming to me.

Success in these contexts is linked to feelings of personal achievement or growth. It can mean using writing as a tool for discovering and actualizing transformative ideas.

For many students who were more internally motivated, journaling was described as the most impactful writing, and therefore the most successful because it was the most likely to induce pleasant feelings and promote clarity and self-discovery. In our study, we noticed a pattern whereby students shared feelings of passion, and even spoke for longer when asked about their personal writing. It appeared to be easier for them to describe what constituted success for them in this genre.

For others in our study, success was defined externally, either through grades given to an assignment or through feedback given by others. Leo stated, “if I’m writing for others, like in the sense that…like..I’m writing something with the intent that other people will read it, I know it’s successful when that strikes some kind of emotion in the person.” Leo’s goal for his writing is to have it move his reader in the way he intends. He strives to change the reader’s feelings more than their position, suggesting that writing for the student inhabits an affective space.

We asked nearly all the students interviewed, “Do you consider yourself a good writer?” Many students were too humble to admit they thought they were good writers (though they also rarely called themselves bad), even when the writing samples they submitted were quite strong. In externally motivated situations, like working for a grade in class, they noted that often it is incredibly difficult to know the instructor’s version of successful writing. In the absence of a full understanding of instructor expectations, they saw these criteria as idiosyncratic. Students were thus particularly uncomfortable using grades as their only judgment of success. At the same time, we found that students reported it was impossible to fully avoid grades as a metric for sharpening one’s self-image as a writer, a source of stress for many.

These findings point to a possibly missed opportunity in faculty teaching. Grades did not appear to be a meaningful measure of success for the writers because they were perceived as measuring expectations invisible to them or not tangibly connected to their own motivations as writers. Grades did not appear to be a meaningful measure of success for the writers because they were perceived as measuring expectations invisible to them or not tangibly connected to their own motivations as writers. Faculty may be able to engage students more deeply as learners by clarifying their assignment goals and providing more space for students to exercise autonomy and authority in defining the audience and shape of their writing.

This tension—between the faculty member’s goals and the writer’s—also manifested itself in conversations about how students construct and enact identities in their writing. Writing studies scholar Kevin Roozen describes the act of writing as “not so much about using a particular set of skills as it is about becoming a particular kind of person, about developing a sense of who we are” (51). In our research, we found that students often experienced that “particular kind of person” with unease when it was difficult to reconcile it with what they perceived as an authentic sense of self. When students were asked to adhere to a disciplinary set of writing conventions and values, they sometimes experienced such tasks as a personal affront or erasure of identity. Other times it seemed like an exercise in delivering on others’ idiosyncratic expectations of them. This may be because many of our interviewees were first- and second-year students new to disciplinary forms of writing. They may not have had time to find and practice participating in the kinds of conversations most compelling to them. Yet it’s striking that so many of the students we talked with did not connect the writing they were doing with meaningful forms of thinking in new fields, raising questions about a potential mismatch in the goals of faculty and students.

For example, Leo explained how, just prior to the pandemic, he had opted to take his first college history class. He was invigorated by the content and spent a lot of time and effort on his first writing assignment for the course. “[It] was like something I enjoyed writing and I thought I had some valuable insights,” he said. But his teacher reacted negatively to what he produced, giving him a grade he felt was unjustified. The next time Leo had to write for that class, his approach changed immensely:

Like Leo, we noticed a number of students attributed such expectations to the professor and not the field, in this case history writing. They also described learning to write as a means of gaining approval from someone they respected.

Another student, Elizabeth, described a similar experience. She took a class with one professor in both the fall and spring semesters. In the fall, she felt like she kept getting the same grade on all of her writing. At the same time, she was learning more about what this professor wanted her writing to look like: “This man does not like fluff, like transitions, not so important, don’t waste word space, these are short essays; just answer the question and you’ll do okay,” she explained. So this semester, she changed her approach.

Elizabeth, like Leo, reports learning how to adapt her writing to the expectations of her professor and experiencing success through that process.

We noted that both students interpreted writing assignments as exercises in what Paulo Freire calls the “banking model,” as opposed to opportunities for the kind of collaborative problem-posing that positions writers as “re-creators” of knowledge (71-86). They sometimes viewed feedback as an opportunity to be filled with the writing knowledge of their professors, but struggled to articulate how this feedback was integrated holistically into their identities as writers navigating different discourse communities. As students were asked to write differently in different contexts, they often described feeling like writing chameleons, adapting their approach to please their professors. Often seeing such writing negatively as conformity, they sometimes described writing as alienating. At the same time, participants demonstrated an awareness of the painful ways in which unexamined definitions of “good writing” can perpetuate linguistic discrimination that marginalizes identities and groups.

For example, Anya perceived that her aspirations and standards for her writing were often overridden by expectations and external pressure. She spoke extensively about her relationship to the English language, which is her only language but not a first language for either of her parents.

Anya felt empowered by her proficiency in a certain kind of academic English, but the cost of such confidence was adopting a set of standards that she also experienced as alienating; pride in “mastery” supports a linguistic norm that marginalizes those who are held most dear. From the conversation, it appeared that Anya, too, never received instruction on how to set her own goals for her writing and reconcile those with the assignments before her.

As student researchers, we noted missed opportunities for empowering pedagogies that clarify instructors’ purposes in assigning and valuing writing in the ways that they do–and inviting students to help shape the assignment and the criteria that would be used to evaluate their work. Particularly during the pandemic, we noted that students desired to engage in writing that felt meaningful and urgent and inclusive of their multiple identities. They also felt that the pressure placed on their relationships with professors was also more intense amidst the isolation of the early pandemic. This meant that professors’ feedback also seemed to carry more weight. Jamie said, for example:

Jamie viewed her writing as an opportunity for social connection–response in the form of validation. In the absence of other interactions, feedback had an especially powerful impact on her self-confidence as a writer. Since the college experience had been largely reduced to coursework in the online environment, this created new pressures for writers and new vulnerabilities to their self-esteem.

These new pressures may be another reason why a number of students in our study turned to journaling during the pandemic, something instructors may wish to consider as they develop their courses. We found that journaling throughout the pandemic allowed for students to disengage from external standards, deadlines, and assignments in the online environment.. Journaling allowed for students to be in tune with their thoughts, feelings, and changes over the COVID year. At the same time, other students reported disengaging from personal writing as they saw their capacity and love for writing wane amidst pandemic-induced constraints. A common theme among the daily journal writers who stopped journaling during COVID was the feeling that writing became more of an overwhelming task rather than something that could add meaning to their life. Prisha, for example, claimed,

I haven’t written much in the pandemic. I used to journal almost every day when I was in college. I used to enjoy it actually but I feel like I’m just not in the headspace to actually enjoy journaling. It feels like everything is a task right now.

Academic pressures felt intensified for Prisha, and she acknowledged the need to scale back.A lot of the feelings Prisha shared with us were felt by another student, Rosario. Being multilingual, a lot of the standards Rosario had to meet did not show flexibility nor acceptance of his own personal and cultural relationship with writing and language as a whole. With the academic stresses of writing during the pandemic—which he saw as a focus on product over process—Rosario understood that good writing in an academic setting is very dependent on others’ definitions of quality writing. He expressed the belief that a lot of these perceptions of what good writing is and who is allowed to be called a writer are strongly tied to classism. Rosario sees his writing identity as intertwined with his identities, including his ethnicity, gender, and positionality as a first-generation college student. He expressed that any universal standards that intersectional students like him have to meet further hinder and silence his voice, creativity, and contributions to public discourse.So how does writing affect the lives of people with identities that are underrepresented in academia? While our dataset is too small to draw definitive conclusions, in this study BIPOC students, especially those who are first-generation college students and multilingual, experience imposter syndrome and insecurity about their language capabilities in this context. At the same time, they are deeply aware that their perspectives are essential to the world-making enabled by the kind of writing that results in social change.

Discussion

Throughout the interviews, we noted that students reflected deeply on their identities as writers as they described what, how, and why they write. We were curious about the prevalence of identity in students’ reflections on their academic and creative lives. What are the variables that contribute to the context of the question: How do we write now? We found the COVID-19 pandemic was an important aspect of the environment our subjects were writing in. The pandemic exacerbated existing inequalities, making them more visible and pronounced. It also prompted collective introspection about what truly matters and invited a critical re-envisioning of work, including writing. In our student-led study, we expressed interest in investigating students’ experiences with writing in order to engage in research that might also be transformative.

- How can learning about students’ perspectives at this moment inform the teaching and tutoring of writing?

- How might academic writing be redefined to enable students to engage in work that feels authentic, inclusive, meaningful, and urgent?

- How can we create spaces that invite writers to reflect on their own goals and bring their whole selves to their learning?

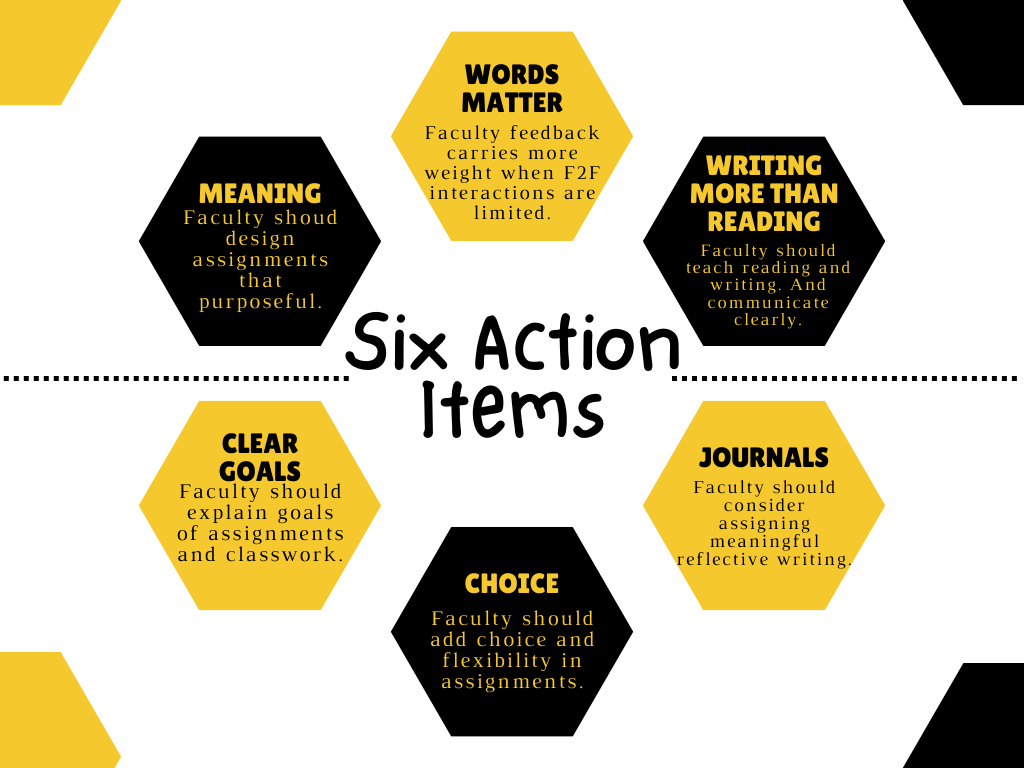

In response to these questions, we have generated six recommendations, or action items, for faculty who assign writing across the curriculum. We recognize that these recommendations are not new, but we believe they can be powerful when framed in the context of local institutional assessments.

The pandemic appears to have made students more attuned to the larger purpose and meaning of their work.

The isolation of the pandemic may have put additional pressures on the faculty-student relationship.

The pandemic further induced a writing-rich environment, perhaps heightening Deborah Brandt’s theory that as a culture we now write more than we read (Brandt).

Students appear to especially appreciate opportunities for journaling and reflection during the pandemic.

Students during the pandemic appreciated when professors clarified the goals of their assignments and lesson plans.

In our current moment, students may particularly value choice and flexibility in their assignments, empowering them to explore questions that interest them and to tap into the diverse forms of authority and experience they bring to assignments.

Such explicit conversations–and pedagogical transformations–might also help students new to a field see faculty expectations as connected to something larger: a vision of community inclusive of their perspectives within the shared language of the class and, possibly, the field. The pandemic, more than ever before, highlighted people’s need to see their identities as a form of living–not something that can or should be avoided or hidden. Skeptical of a culture of self-optimization and hegemonic ways of knowing and doing, the students in our study were eager to tap into the liberatory potential of other ways of working and being. Writing centers are uniquely positioned to re-envision knowledge practices as inclusive of these perspectives in the post pandemic future. Student-led assessments like this can feed back into institutional conversations with faculty, students, and staff, participating in a shift in the culture of writing and work on our campuses.

Works Cited

Anderson, Paul, et al. “How Writing Contributes to Learning: New Findings from A National Study and Their Local Application.” Peer Review, vol. 19, no. 1, 2017, pp. 4-8.

Anderson, Paul, et al. “The Contributions of Writing to Learning and Development: Results from a Large-Scale Multi-Institutional Study.” Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 50, 2015, pp.199-235.

Anson, Chris M., and Deanna P. Dannels, “Developing Rubrics for Instruction and Evaluation.” Strategies for Teaching First-Year Composition, edited by Duane Roen, et. al., NCTE, 2002, pp. 387-401.

Blum, Susan D., editor. Ungrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (and What to Do Instead) West Virginia UP, 2020.

Brandt, Deborah. The Rise of Writing: Redefining Mass Literacy. Cambridge UP, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316106372.

Eodice, Michele, et al. The Meaningful Writing Project: Learning, Teaching, and Writing in Higher Education. Utah State UP, 2017.

Eodice, Michelle et al. “What Meaningful Writing Means for Students.” Peer Review, vol. 19, no.1, 2017, pp. 25-29, https://scholar.stjohns.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=english_facpubs.

Felten, Peter, and Leo M. Lambert. Relationship-Rich Education: How Human Connections Drive Success in College. Johns Hopkins UP, 2020.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Berman Ramos, Continuum International, 2005.

Hall, R. Mark, Mikael Romo, and Elizabeth Wardle. “Teaching and Learning Threshold Concepts in a Writing Major: Liminaity, Dispositions, and Program Design.” Composition Forum 38, Spring 2018.

Inoue, Asao B. Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies: Teaching and Assessing Writing for a Socially Just Future. The WAC Clearinghouse and Parlor P, 2015.

Kuh, George D. High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter. Association of American Colleges & Universities, 2008.

Lincoln, Yvonna S., and Egon G. Guba. Naturalistic Inquiry. SAGE Publications, 1985.

Naftzinger, Jeff. “A Definition of Everyday Writing: A Writer-Informed Approach.” Lifespan Writing Research: Generating Murmurations Towards an Actionable Coherence, edited by Talinn Phillips and Ryan Dippre, WAC Clearinghouse, 2020, pp. 81-95.

Roozen, Kevin. “1.0 Writing Is a Social and Rhetorical Activity.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts in Writing, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State UP, 2015, pp. 17-19. https://doi.org/10.7330/9780874219906.c000b.

Roozen, Kevin. “Writing Is Linked to Identity.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State UP, 2015, pp. 50-52. https://doi.org/10.7330/9780874219906.c000b.

Sangaramoorthy, Thurka, and Karen Kroeger. “In the Current Climate, Rapid Ethnographic Assessments Are the Research Method We Need.” Interview by Emily Cousens, London School of Economics Blog. Accessed October 13, 2022.

- The co-authors, whose names appear alphabetically, would like to acknowledge the team that designed this study and collected and analyzed data on its behalf: Angel Barraza-Estrada, Phebe Cox, Jack Friedman, Ryann Liljenstolpe, Kat Lin, Dominique Morra, Oliver Ricken, Seerat Sandhu, Gabriel Scherman, and Alexander Rodriguez. ↵

- All names cited in this study are pseudonyms. ↵