7 Rethinking Gendered Care Work: Towards a Culture of Care-Based Inquiry in the Writing Center

Vanessa Abraham, Emily Poland, Ben Warren, and Anna Wendel

Dickinson College

Challenges in the Post-pandemic Writing Center

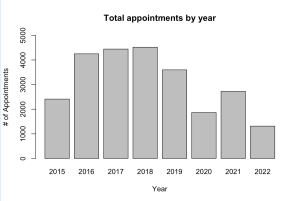

The unanticipated catastrophe that was the COVID-19 global pandemic impacted every area of higher education, and the writing center was no exception. Between 2016 and 2019, the Norman M. Eberly Multilingual Writing Center at Dickinson College averaged close to 4,200 appointments each year. When the center adopted virtual tutoring due to the pandemic, appointments dropped by 56% to fewer than 1,900 in 2020 (see fig. 1). This decline reflects a moment of great disruption that negatively impacted the teaching and learning of writing.

As rising juniors who entered college in the fall 2021 semester, all our experiences working in the writing center occurred mid- or post-pandemic. In addition, like many of the students with whom we work, we experienced the impact of various online, hybrid, and in-person high school experiences on writing instruction. Gone were the essay assignments, peer review sessions, and other hallmarks of a typical high school classroom invested in teaching effective writing skills. Instead, students were thrust into a world of short responses and asynchronous written feedback that contributed to a lack of writing-intensive education and stagnated critical thinking. Furthermore, disparate access to resources throughout the pandemic meant that learning experiences varied greatly for each individual student, exacerbating challenges during the transition to higher education. Given how writing instruction changed during COVID, many students entered college with inadequate writing experience and faulty expectations, making them unable to adjust to the demands of the college environment as a whole, let alone the stress surrounding college papers.

In short, when it came to their development as writers, students lacked proper care during the pandemic. Now several years after the height of quarantining and social distancing, students need direct care and interpersonal relationships to develop their writing skills, and the writing center is the perfect place to reimplement this form of connection post-pandemic. In this essay, we introduce the concept of “care-based inquiry” in the writing center. Care-based inquiry is a set of dialogic practices for writing center tutors that empowers them to expand what writers understand to be possible in the center, set boundaries that protect their own well-being, and more effectively serve writers by scaffolding for an individualized and fulfilling session. This essay draws on previous scholarship on care, our personal experiences as tutors expressed in the form of anecdotes, and qualitative analysis of transcribed sessions from our center’s archives to detail a care-based approach to working with writers post-pandemic and beyond.

Fig. 2. Anecdote[1] 1: Gender Bias, Productivity, and the Care Model.

A session that Anna facilitated early in the year catalyzed our work on what we came to call care-based inquiry because it highlighted some shortcomings of a commonly taught rapport building model. Anna was working with a first-year seminar student in a course that focused on writing the personal essay. As a new hire, she followed the textbook rapport building model taught in the tutor training course at Dickinson (Fitzgerald and Ianetta 56-57). She offered a friendly greeting to the client, asked him about his writing process, and then prompted him to set the agenda. He told her that he saw another male tutor the night before to work on his argument and thesis. He felt confident and only wanted to work on his grammar. Anna was excited that he was feeling so confident in his work; she certainly wasn’t feeling as confident when she was in her first few weeks of college. She didn’t think that she needed to ask any more questions. They moved on to reading through the paper.

Within the first few paragraphs, Anna realized that he was writing mostly summary and lacked a thesis, even though the prompt asked the students to advance an argumentative claim about an essay by Montaigne. She affirmed his introduction as a summary of key points, and suggested that they work together to reverse outline the paper in order to find a thesis by thinking about what argument he wanted to make (Fitzgerald and Ianetta 92). She noticed him starting to shut down and become less receptive when she asked him questions about global concerns. When Anna asked him what he talked about with the tutor the day before, he responded: “When I saw the tutor yesterday, he said it was fine.”

At first, she thought his comment meant that there was a miscommunication on her part, so she further explained why she asked questions about argument and clarity. But this led him to push back against her suggestions. She could tell that he was getting frustrated, and she wanted to care for him. She wanted to get to the root of his frustration, whether it was writing anxiety, desire to complete the assignment, or conflicting advice from tutors. She also wanted to help him care more about his writing process since he hinted that he saw the seminar as a throw away class rather than a valuable introduction to college writing. And she also wanted to care for his paper since he had not quite met the requirements of the rubric. Despite these efforts, she kept hitting an emotional brick wall and was exhausted by the end of the session.

This session raised a number of questions that ultimately informed our research. At first we wondered about the gendered implications and if he was resistant to Anna’s suggestions as a female tutor because he already had the affirmations of a male tutor. But we then wondered if he could have had anxiety about his writing that he didn’t articulate to Anna, or if she didn’t ask enough questions at the beginning of the session. Additionally, we wondered if it was possible to execute a slow, intentional kind of care when the writer wants to be productive and see results quickly, and if gender had an impact on either of these tendencies. Finally, we considered whether he had incorrect assumptions about the kinds of care work we do in the writing center.

Observations on Gender

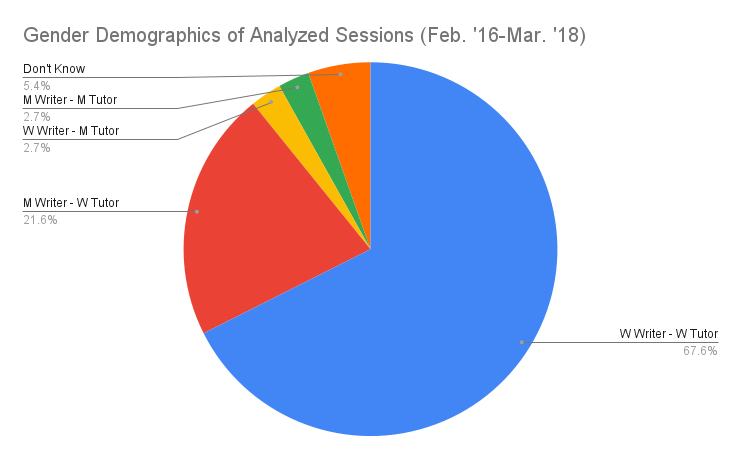

To pursue our questions about gender dynamics prompted by Anna’s session, we analyzed thirty-five transcripts of sessions carried out in the center between 2016 and 2018[2].

We had access to both the transcripts and the original recorded audio of the sessions as well as information about the demographics of the participants[3]. We sought to identify gendered patterns of behavior using self-identified pronouns as a proxy for gender. We found that by and large, the tutoring behaviors we observed in the sessions mirrored trends described in previous research on gender in the writing center. In our analysis, we identified both the feminization of the writing center, a concept advanced in the work of Thomas Spitzer-Hanks and Michelle Miley, among others, and several key behavioral differences by gender, noted by Mary Traschel, Ben Rafoth et al., and Harry Denny. We noted, however, that the strict binary definitions of gender in the existing literature clashed with the non-binary reality of our center.

In roughly two-thirds of the sessions we analyzed, both the writer and the tutor self-identified as women, while twenty percent of sessions were between a male writer and a female tutor, and just two sessions were held by male tutors, one each with a male and female writer. Given the small number of sessions with male writing tutors in our sample, we focused primarily on the sessions between female tutors and male writers. We had a fair number of these sessions to analyze, and they showed most clearly gendered differences in behavior among session participants.

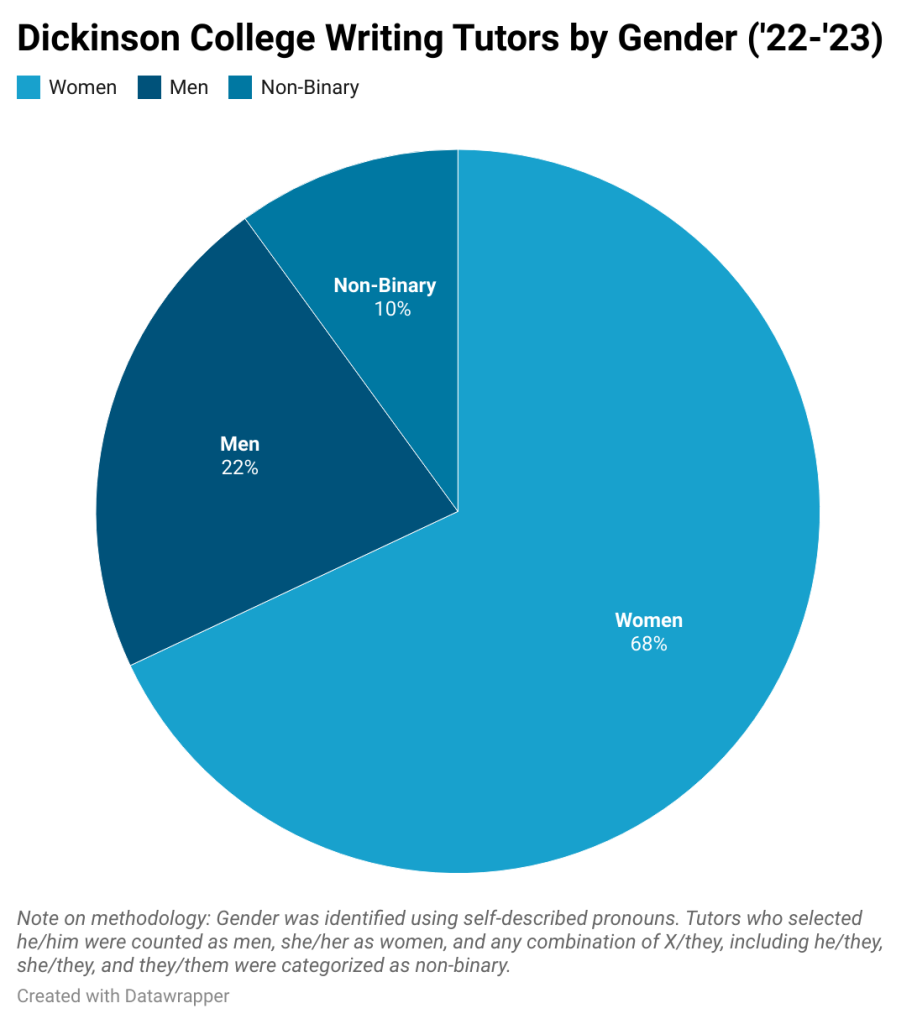

Miley and Traschel observed that the writing center is considered a feminized space, though they differ on whether this observation is a positive, negative, or neutral characterization (Miley 18). Spitzer-Hanks, in turn, has argued that the feminization of the writing center is both a quantitative and a qualitative process. Women make up the majority of tutors in the writing center community more broadly, and this is certainly true of our center as well. Thus, as a space inhabited primarily by women, the writing center is feminized. Based on data from 2023, around seventy percent of our tutors at Dickinson are women (see fig. 3), as are sixty percent of the students who use our services (see fig. 4). The feminization of the writing center, however, as Miley writes, does not occur only because more women exist in our spaces (Miley 18). Rather, the work of the center is also feminized by its focus on care: we help people, and this “nurturant activity” is considered feminine (Trachsel 28). In her analysis of gendered divisions of care work in academia, Traschel explains that those with “relative privilege and power,” typically men, often perform care work by assuming the responsibility of “tak[ing] care of” people’s needs, while other, less privileged classes of people are left with the brunt of the “care-giving labor” (30). Applied to the writing center, we find that men tend to “take care of” issues that arise in their writing center work, addressing a rogue sentence or mangled narrative structure, while women are more likely to “care for” the writers, ensuring that they feel comfortable and welcomed in the center. While we do not want to over-generalize these findings, they fit the patterns of the transcripts we analyzed.

In sessions with female tutors and male writers, we observed that the stereotypical conversation “rituals” most common in sessions of this gendered type include negative body language and dismissiveness by the male client (Rafoth et al. 4). While we cannot speak to the former claim, since we did not observe the physical sessions, the latter held true in the transcripts we analyzed. We found that male writers demonstrated overconfidence in their work, which often manifested in the dismissal of higher-order concerns introduced by the tutor and a desire to merely check their grammar instead. This overconfidence was rooted in a productivity mindset, as male writers tended to focus on making quick fixes. In the context of Traschel’s work, this is intriguing: the male writer, not the female tutor, displayed the productivity orientation–the desire to “take care of” issues–that she associated with privileged classes. In many cases, these writers demonstrated this mindset via a prominent focus on lower-order concerns. We observed that male writers often hinted at the existence of higher-order issues–expressing frustration, for instance, when they had difficulty understanding the prompt for an assignment– but in the end guided the session towards an ending. One student, after mentioning the shortcomings of his current draft, remarked that he was unconcerned about the paper, since he had received good grades on his earlier work in the class. He told the tutor, “I feel like at this point anything I hand in he’ll give me a 95.” During another session, when Anna asked a writer to clarify a statement about the paper’s content, he told her that she was not his “target audience,” so he did not need to explain himself any further.

Each of these clients worked against the mission of the writing center as a collaborative, generative space when they dismissed the queries or concerns of their tutors. While we read this dismissal as a case of overconfidence and a hyper-fixation on grammar, the most common uniting theme among male writers was neither a focus on grammar nor overconfidence, but an overwhelming desire to be productive during a session. The typical male student had a task in mind when he walked into the writing center: to leave with a better paper, preferably one that would receive an ‘A’ grade. In contrast to the stated mission of our center, to “support writers … as they develop their writing processes and increase their repertoire of writing skills,” these writers focused primarily on the immediate goal of improving their current assignment in pursuit of a better grade (“The Norman”).

How then did female tutors do the care work articulated in the center’s mission statement with the male writers who dismissed them? In line with a 1998 study by Laurel Johnson Black on writing conferences between students and instructors, which found that female students tended to be more “tentative” and “evasive,” female tutors in our analysis often reacted to overconfidence with conciliation, acting overly apologetic about their contributions to the session (qtd. in Denny 102). They oriented their work in the center around the notion of care, as Traschel wrote, not productivity. When male writers exhibited a level of confidence disproportionate to the quality of their work, female tutors were more likely to accept the optimism of the writer than to question his characterization. Even in cases where it would have been helpful for the tutor to challenge a claim made by the writer, we found that female tutors rarely acknowledged these issues when the writer himself did not bring them up. When female tutors articulated their concerns with overconfident writers, they often used apologetic language. They expressed concerns about overstepping writers’ boundaries, even when there was no indication that the tutor might have violated academic integrity guidelines.

One female tutor, in a session with an older male writer, apologized numerous times for asking questions about the professor’s expectations for the assignment. She inquired, “Oh sorry before I go on…is she okay with you inserting yourself in the paper?” After he answered the question, she added, “Yeah okay sorry for that.” Her question was not only legitimate, it was clearly useful to the session. Yet she felt the need to apologize for asking. In another session, the female tutor addressed a grammar question from the male writer. After she clarified the point, she apologized, saying “sorry, I was just trying to explain,” and a few seconds later, “sorry I just didn’t want to like cross things out on your paper.” From the context of the exchange, it is clear that she did nothing wrong; she simply helped the writer choose the right word in a sentence. But she felt that she had to apologize for this intrusion. During that session alone, the tutor used the word “sorry” on eight separate occasions.

While conciliation in the face of overconfidence often hindered their ability to engage constructively with problematic male writers, the female tutors we analyzed also prioritized the holistic development of the writer over the specific task at hand, and thereby aligning with writing center best practices and our center’s mission. “How are you feeling about this?” was a common refrain from these tutors, who were more likely than their male counterparts to provide emotional as well as academic support to writers. They prioritized treating the student as a person first and then a writer.

At Dickinson, we observed two major findings in the existing literature on gender in the writing center – the feminization of the center and gendered differences in tutor-client behavior – to be more or less accurate. Our center is feminized by the fact that we do care work and by the demographics of our staff, the majority of whom identify as women. And we observe meaningful gendered differences in the way men and women tutor – differences which often mirror established stereotypes rooted in gender binarism. We find, however, that we need to analyze these behaviors outside of a strictly binary gendered lens. As we developed a more nuanced analysis of the work done in our own center, we came to form our own ideas about the non-binary writing center.

Going Beyond the Binary

One major flaw we found within the existing scholarship was the binary nature of their assertions, which placed behaviors within a male/female context: female tutors generally act one way, and male tutors another. Indeed, our own observations had also existed within this male/female binary. We noticed female tutors’ conciliatory mannerisms alongside male writers’ tendency toward productivity. This analysis completely disregards the nature of our writing center, and Dickinson at large, both of which exist beyond a gender binary. Approximately 10% of our tutors for the 2022-23 academic year self-identified using pronouns other than he/him/his and she/her/hers. These pronouns were self-reported by tutors as a recent initiative on behalf of our staff to create a more inclusive and welcoming environment recognizing our tutors’ diverse identities. (Our appointment forms include an optional section for clients to add their pronouns, but we had only started to ask the same of tutors.) While pronouns are not the only way to determine self-identifications of gender, they are what was accessible to us and, therefore, the most reflective metric of a non-binary writing center. Thus, it soon became clear to us that the only way to truly capture the nuances of these behaviors would be to expand our scope beyond binary representations of who could and should display them.

Not only do our college and writing center consist of non-binary populations, but we also soon found that the behaviors previous scholarship tended to place in gendered categories actually defied these binaries. People identifying as women could demonstrate productivity mindsets even if they traditionally were viewed as masculine and associated with men. Likewise, people identifying as men could express desire to be cared for or themselves perform caring and conciliatory actions traditionally viewed as feminine and associated with women. These behaviors were not exclusively masculine or feminine and this observation, alongside the non-binary reality of our center, led to our focus on behaviors as separate from gender. This choice is by no means meant to assert that gender can be neglected in the writing center. In fact, our experiences as tutors and clients within our center have shown gender plays an undeniable role in how tutors and writers interact with each other, impacting conversation dynamics, body language, comfort during sessions, and much more. Rather, our research is meant to expand pre-existing scholarship by analyzing traditionally gendered behaviors and actions outside of their gendered contexts. This shift away from gender-based argumentation rejects both the dichotomy of gender and the expectation of particular roles based solely on one’s gender identification.

Transcript Example #1: Breaking Binaries of Gender Performance

In one of our transcripts, we observed how interactions within the writing center upend traditional, gender-based perceptions of behavior, demonstrating the need for thinking beyond the binary.

This session from March 2016 consists of a male tutor and a female tutee. The tutor was a sophomore and the writer was a junior. Both students spoke English as their first language. The writer, who had brought in a cover letter for her internship application, clearly demonstrated a productivity mindset throughout the session. The session actually begins with the tutor confirming some of the writer’s productivity oriented requests: she needs to leave the session at a particular time (“ …you have to be out of here by one-thirty, you said?”) and she has scheduled a follow-up appointment with the same tutor for later that day (“I also noticed that you set up another appointment with me later in the day”). Already this student seems to orient visits in the writing center around efficiently meeting specific goals she has set for herself. In fact, their continued discussion reveals this is far from her first visit to the center with this particular piece (“I’ve been here at least three times with this”). This detail is even more striking when considering that cover letters are typically no longer than a page of text.

Since the tutee is applying for an internship, the stakes are particularly high, reflected in her repeated visits and attitude about the cover letter. The tutor tells her the purpose of the cover letter is to “sell yourself,” and the writer comments that the internship “only [accepts] five people.” Thus, the writer’s purpose is to write a strong cover letter in order to land one of the internship spots. Her repeated visits and other actions may indicate that perfectionism is arising from her desire to win the internship, just like a writer who visits the writing center purely to ensure a higher grade on their paper. Despite the tutor directly admitting that he feels he has addressed her work to his fullest capabilities (“I don’t have anything left to say”), this writer decides she “definitely will” keep her fifth appointment. When considering this choice alongside the polished nature of her paper and the tutor’s general lack of comments, it seems like the writer is treating the session as if the tutor is on the review board for these internship applications. Her strong desire to get the internship leads to repeated visits and the indication that she will not be satisfied until he assures her the letter is perfect. As previously stated, this transcript shows how the behaviors we have discussed are not tied to particular gender identifications. The productivity mindset of this female writer defies the convention of productivity as a stereotypically masculine trait.

Fig. 6. Anecdote 2: Breaking Down Assumptions About Gendered Care Models.

With this established conversation in mind, we started to think about the nonbinary reality of our writing center, and the impossibility of imposing a gender binary framework on our center. We started to investigate the gender binary in the writing center when Anna told us a story about a female student with the productivity mindset that we had been ascribing to male clients. This student came to the writing center during finals’ week with a longer paper in classics that was due soon. The assignment prompted a close reading that placed texts in conversation with one another. Anna began the session by following the standard rapport building model, greeting her and welcoming her to the center, and then moving to the agenda-setting portion. The client, who was anxious about finals, said that she had written some questions in the margins of her document that she specifically wanted feedback on, but also noted that she was open to any feedback.

As they read through the paper, Anna realized that the writer was very focused on describing the history of the time period instead of close-reading the texts and conversing with her historical documents. Anna asked the writer some questions about audience and genre because she thought the writer had misunderstood disciplinary conventions. The writer was repeatedly defensive and rejected the questions that Anna asked her about argument and form. She really only wanted stylistic and grammar corrections, which made up the majority of the content of the notes that she mentioned before. While a typical session is forty-five minutes, this student stayed for an hour and forty minutes. At the time, Anna empathized with the writer’s anxiety and wanted to provide the time to care for her. Anna was scheduled for a two-hour shift, so she chose not to ask the writer to leave. After the session ended with little collaborative conversation, Anna was physically and mentally exhausted.

As we reflected on this session together, we were curious if a care work or productivity mindset could be linked to a set of gendered behaviors, and what might happen when these mindsets clash with writers who see the writing center as purely productive. We also considered whether there are better ways for tutors to care for writers in order to have more effective, empathetic conversations that protect both parties, regardless of gender. We started to think about the best ways for writers to care for tutors, primarily by educating writers on the goals of writing center work so they aren’t expected to act like human Grammarly stamps. And we were curious if there is a way for tutors to set boundaries with writers to keep an ethic of care in place while maintaining their own mental and physical health.

The Ethics of Care

Particularly in post-pandemic times, writing center practitioners need to grapple with what an ethic of care would look like in writing centers. Care, as observed by Joan Tronto, makes stakeholders of its recipients (Tronto 22-23). Within the context of interpersonal relationships, this means that the needs of each party must be addressed and considered in order for the participants to create meaning together. Virginia Held similarly notes how care is both relational and interdependent: a mutually acknowledged desire to reach an understanding by agreeing upon a conversation’s purposes is the key to more effective care (Held 14). While goals and objectives are not necessarily shared by all involved in these interactions, aligning differing perspectives provides the best chance of meeting as many needs as possible. To arrive at the best outcome for all involved in interpersonal relationships, including writing tutoring sessions, it is crucial that participants understand and articulate their own needs. This might consist of setting boundaries to protect one’s comfort level in an interaction or expressing a willingness to find common ground with one’s conversation partners.

Alongside the ability to communicate one’s own needs, a level of sensitivity to the needs of others is amongst Held’s list of qualities necessary for ideal care (Held 11). This calls for responsiveness on behalf of participants when others’ needs are expressed as well as a sense of patience to determine, and even to anticipate, conversation participants’ needs that could be implicit or subconscious. Such sympathetic and empathetic attitudes value personhood over goal-oriented productivity mindsets in conversation, giving participants space to recognize the value in their discourse. Above all, optimal care attempts to get everyone as close to being on the same page as possible. This, in turn, makes it significantly easier to generate ideas in conversation, leading to more fruitful and worthwhile discussions that make all participants feel validated and cared for, regardless of the specific dynamics of an interaction.

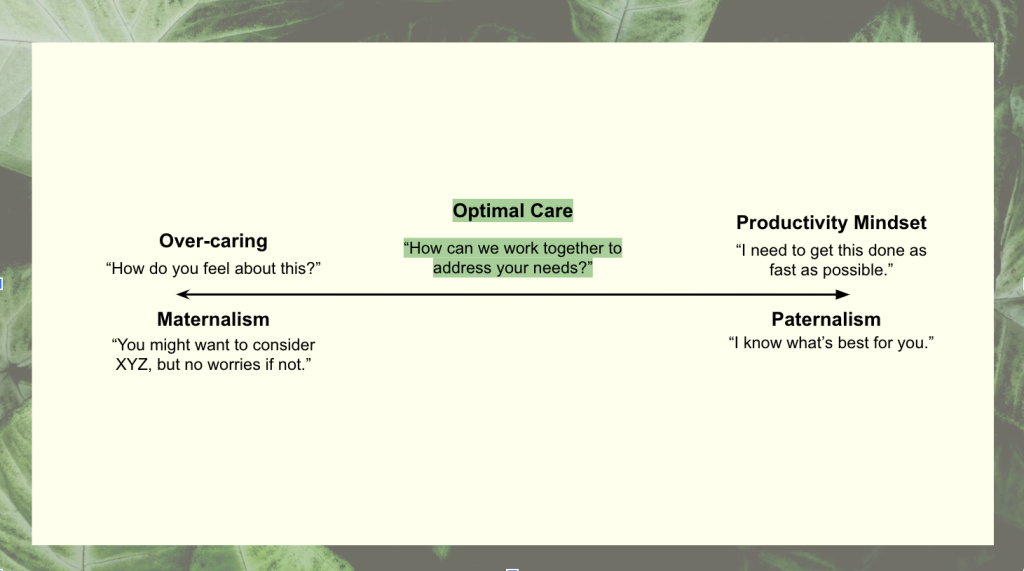

In the tutor-writer relationship, maintaining an ethic of care in the care work done by tutors can help both parties feel invested in a session. For example, the act of building rapport at the start of and throughout a session contributes to a lasting connection that improves the quality of the session and, ideally, the retention rate of writers visiting the center. For both tutor and writer to feel respected and cared for, productivity cannot be the only focal point of a session. For both tutor and writer to feel respected and cared for, productivity cannot be the only focal point of a session. However, an overemphasis on care can easily turn into overmothering or paternalistic behaviors. Thus, what we searched for was a way to use these theories surrounding care to negotiate care-oriented and productivity-oriented mindsets and find the most effective balance of the two.

Care vs. Productivity

As we observed in our own experiences and our analysis of session transcripts, productivity and care can be in conflict during writer center sessions. While tutors are trained to care for a writer in their entirety, writers tend to enter the center with a desire for success and completion: finished papers that earn As. With competing priorities at play, setting the agenda for a session becomes difficult. This emphasizes the importance of trying to see eye to eye with a writer in a session, something best done by demonstrating a kind and responsive attitude. We have also seen, though, that tutors can overexert themselves in an effort to best care for writers. Often, the amount of emotional and intellectual labor put in by a tutor is not matched by a writer. The writer may be indifferent to the session (or at least indifferent to anything that does not feel explicitly productive, such as rapport-building or structural concerns within a paper). There is no guarantee that they will become active participants in their own care, let alone respect the needs of the tutor they are working with. The stress surrounding one’s paper can lead a writer with a productivity mindset to have a one-track mind in regards to what they think needs to be accomplished in the session. This is exactly how tutors end up in conversations in which a writer, insisting the session focus exclusively on grammar, pushes back against any other suggestions a tutor may make and rejects everything except what they want to hear. This sort of behavior actually makes sessions less productive as priorities are not clearly established and agreed upon. However, this does not imply that writers oriented toward productivity do not want to be cared for. In fact, some of the writers most geared toward productivity require care precisely because of the high levels of anxiety this mindset creates. These writers, stuck between a need for care and a need for productivity, ask tutors to provide the impossible.

Transcript Example #2: Reconciling Care and Productivity for Tutor’s Wellbeing

Returning to our previous transcript example, one clearly observes the clash between desires for productivity and care inherent within the session.

Once the tutor and writer have covered the basics of her cover letter (i.e., did she answer all the questions asked by the prompt?), the tutor struggles with what to say to the writer. He frequently hesitates, beginning statements by expressing how he feels he has helped all he can (“Um, other than that, I really don’t – there’s nothing…”), then pausing and reframing them to reassure the writer of the quality of her work (“this is a very polished draft”). He explicitly notes a lack of feedback for the writer, primarily because her piece has already been heavily revised, but sensing that she is not satisfied with this response, continues to care for her in spite of his own discomfort. He says, “You’re definitely on the right track,” “I’m sure you’re very nervous,” and “it’s obvious you put a lot of work into this.” He attempts to acknowledge and validate her feelings of uncertainty while highlighting the visible effort she has put into her work. However, having trouble balancing these aspects of care and productivity, especially in the face of a writer insistent on a flawless cover letter, the tutor seems to talk himself in circles. Seemingly addressing all he has thought of to say, he is left at a loss for words while the writer still craves unattainable comfort. He tells her to take deep breaths and says her work reads well, but this is not enough. Therefore, the session ends with the emotional exhaustion of the tutor and a writer who may still hold some doubts (evident in the fact that she declines canceling her future session). Better balance of the desires for care and productivity, on the part of both the writer and the tutor, would result in less of an emotional burden for the tutor and further satisfy the writer.

Transcript Example #3:

The ease with which an overemphasis on care can cause tutors to fall into maternalistic or paternalistic behaviors presented itself in our transcript analysis. In one specific transcript, a writer brings in an outline for a paper due the same day. At the very beginning of the session, the writer makes it clear that he is operating on a strict deadline:

Mostly I want to work on the coherency of my outline because I need to finish writing it later today. I want to make sure this is going to follow and that the thesis is good and then I can just develop off of this.

In stressing that his outline needs to be coherent so he can finish the rest of the paper later in the day, the writer opens the session with a productivity mindset. Not only does the outline need to be completed as soon as possible so that the rest of the paper can follow, it also needs to be coherent and “good.” This sense of urgency underscores the rest of the appointment as both the tutor and the writer attempt to negotiate priorities for the session.

The tutor, when presented with the writer’s unyielding productivity mindset, switches rapidly between paternalism and maternalism as she tries to meet his needs. As she attempts to motivate the writer to focus on what he can practically achieve on his deadline, she inadvertently assumes paternalistic behaviors. When the writer prioritizes their foci for the paper, the tutor uses their authority to insinuate that some of the content could be difficult to work with:

W: Especially this one I put up top because this is gonna be most important… this is going to be my why focus… whereas this is more of a what focus.

T: Right yeah, so I think… I think this one might be a little bit harder to work with um ok.

Similarly, the tutor also exhibits maternalistic behaviors. In overcaring for the writer, she often repeats what she likes about the paper in an attempt to be reassuring. The writer does not respond to the tutor’s attempts at care, instead suggesting that the appointment needs to move forward in drafting a plan.

T: I like that your plan is to use him in the conclusion…I like that idea.

…

T: Do you feel comfortable with that?

…

W: We should draw a plan off this now.

…

T: Awesome, awesome. Do you have any other questions about it, or anything else you want to go over or anything?

…

W: Yeah, I’m like working overtime.

In attempt to care for the writer under his deadline and his productivity mindset, she exhibits both maternalistic and paternalistic behaviors—both of which infringe on the writer’s agency. The tutor struggles to find a practice of optimal care that honors the wishes of the writer.

Care-Based Inquiry

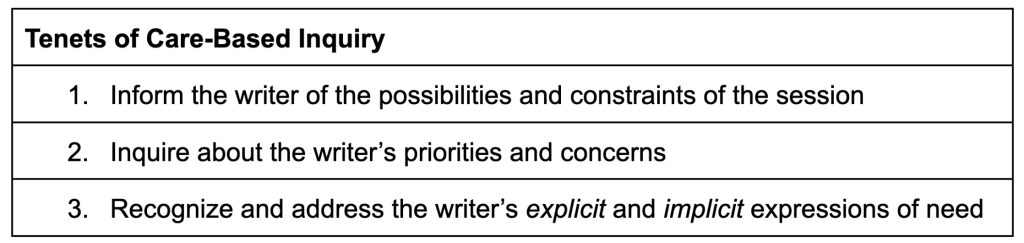

In response to the challenges posed by the tension between care and productivity in writing center sessions, we propose a new practice we call care-based inquiry (CBI). CBI is a set of techniques that allows tutors to alleviate some of the issues we have observed and facilitate a rewarding session for both parties involved. We see CBI as a more human-focused extension of the common rapport-building model, but instead of relying on small talk in the first few minutes of a session, tutors practicing CBI scaffold for care in an individualized, flexible, and impactful manner throughout their time with a writer. There are two main tenets of CBI: tutors must inform the writer about the possibilities and constraints of the session, and they must address both the writer’s explicit and implicit expressions of need. Through these two main practices, tutors can help writers achieve educated agency, at which point the writers possess both knowledge of the tools available to them in the center and the empowerment to get what they truly need out of a session.

By directly addressing what is and is not possible in a writing center session – from the stages of writing we can help with to the amount of time we can allocate to a single client – tutors align their expectations with the writer’s, avoiding possible frustrations for both parties. One of the major obstacles that tutors face in the writing center is the disconnect between what they understand to be the goals and constraints of the center and how the writer understands the same. This is a root cause of the common observation that productivity-minded writers hone in on grammar and lower-order concerns. They may not see the writing center as a place to brainstorm, outline, or discuss issues of content. Not only does articulating the optional pathways open the writer’s mind to a larger scope of practices in the session, but it also protects the tutor’s boundaries.

Often, as shown in a number of the examples in this article, writers ask tutors for support they cannot provide. These situations are uncomfortable and emotionally draining for tutors, as well as unfulfilling for writers. CBI empowers tutors to articulate that they cannot rubber stamp a student’s paper, nor guarantee them success, only provide them writing support to the best of their ability. When tutors open up the possibilities of a session to writers by explaining the full range of work we do in the center and clarify their own boundaries, sessions become more fulfilling and effective.

Beyond understanding the possibilities and constraints of a writing center session, a crucial aspect of CBI is that the writer feels heard. The CBI approach to writer’s agency centers around the ability of the tutor to recognize and address both explicit and implicit expressions of need. In the traditional model of rapport-building, tutors simply ask the writer what they want to work on and build a session around their direct answer. Some writers respond with explicit expressions of need or statements immediately recognizable as guiding factors in a session. When a writer tells their tutor that they want to brainstorm about a topic or they want to focus on the transitions between paragraphs in their essay, these are explicit expressions of need. We argue that traditional ways of rapport-building do not effectively address writer concerns. What tutors are not trained to regard are the implicit counterparts to rapport-building questions. Many new college writers have not had the opportunity to think about writing conventions and mechanics to the degree that trained writing tutors have. They often do not possess the same language to describe their needs in a session that tutors do, which can result in miscommunication.

When a writer seems anxious about a section of their paper, when they make an off-hand interjection about failing to understand part of the prompt, or when they seem confused about content matter, they are implicitly expressing their needs. This does not mean that tutors should try to intuit the needs of writers and take over a session based on their guesses. We merely suggest that when tutors pick up on these anxieties, remarks, and hints, that they begin an empathetic line of inquiry. Oftentimes, simply asking a question like “What is tripping you up here?” or “How do you feel about this part of the prompt” can kickstart a conversation that leads to a more fruitful session than if the tutor simply addressed the needs explicitly articulated by the writer.

The ultimate goal of practicing CBI is to help the writer create a high level of educated agency, which we define as a powerful combination of understanding what is possible in a session and feeling that their true needs are addressed. The ultimate goal of practicing CBI is to help the writer create a high level of educated agency, which we define as a powerful combination of understanding what is possible in a session and feeling that their true needs are addressed. When tutors actively discuss the writing center’s goals and available resources, they empower writers to think more broadly about the center and the possibilities of the session. When they clearly set their own boundaries, they protect themselves from discomfort and emotional exhaustion, while shielding their clients from a potential frustration. Finally, when they pick up on the subtle ways writers express themselves – the little anxieties, the body language, the throwaway comments – they open up richer sessions that better serve the writers.

A transcript between a first-year writer and his junior tutor brings to bear the importance of addressing both explicit and implicit expressions of need. Almost immediately after discussing the prompt of the writer’s paper, a multi-part essay about environmental issues and their impacts on everyday life, the writer voiced implicit expressions of need. The writer interjected, “Oh [expletive], is overpopulation an environmental challenge?” indicating that he may not have seen a key connection between subject matter and part of the prompt. A few seconds later, he remarked that he “wrote this, you know, in the course of one day.” Finally, in response to the tutor reading part of the prompt, he said, “I’m not sure I did that.” Every indication from the first section of this transcript pointed to a session focused on higher-order concerns such as making clearer connections between course content and the essay prompt and addressing the prompt in full.

Yet when the tutor earlier asked the writer what he wanted to work on, he responded: “Well, mostly I’m just bringing this in for grammar.” Clearly, something went wrong. Whether the writer was overconfident about his paper or lacked the vocabulary to express that he was worried about higher-order concerns, the only issue the writer explicitly articulated was grammar. The tutor in this session attempted to guide him back towards higher-order concerns, but since he already set the primary agenda of the session on grammar, it was a futile effort. Indeed, the two students spent most of the time in the session on sentence-level issues. In this session, when the tutor failed to address the writer’s implicit expressions of need, she missed an opportunity to help the writer confront those issues. She could have paused after he identified his misunderstanding of overpopulation or talked to him about his writing process when he said he wrote the paper in a day, or she could have honed in on making sure his paper addressed the specific section of the prompt he may have missed. Instead, she allowed the session to steam ahead into less pressing lower-order concerns. Using CBI techniques would go a long way towards making this session more effective.

Transcript Example #4: The Productivity Mindset as a Missed Opportunity to Apply Care Based Inquiry

Another session in the Dickinson College Writing Center’s archives also highlights the necessity of understanding a writer’s implicit and explicit expressions of need. In the former session, addressing the implicit need of the structural argument meant communicating about a central definition in order to align the tutor’s and writer’s mindsets. Once they did so, the session could move along efficiently. In this session, however, the writer voices several structural implicit needs, but because of his productivity mindset and lack of educated writer’s agency, the care work that the tutor provides suffers. Moving through the session reveals these themes at several key points.

Ordinarily, understanding the context in which a tutor is operating with the client is an ideal way to practice CBI, but this session fails to build rapport while also interrogating expressions of need. For example, on the first page of the transcript, the writer announces his implicit expressions of need in the form of abbreviated professor feedback:

T: So you handed this in already?

W: Yeah and I got a C…which was some shit because it was really good paper… and he just kind of gypped me on it. [The professor] gives us a super vague question and then like gives us like all these like specific things to hit and it’s like I don’t know it’s kind of just like I wrote what I thought was a good paper and it just wasn’t what he was looking for at all so (sigh).

T: O.K., in terms of content?

W: Uh…structure was fine. It was content. He was looking more for… uh… analysis of the books.

A listener can quickly pick up on a few key aspects in the first few moments of the transcript. First, his implicit expressions of need highlight his global concerns: the writer did not understand the prompt, and his paper was missing analysis. Using the CBI method, these implicit expressions of need would be the center of a tutor’s focus early on in the session. However, there is a second factor at play which compromises how well the tutor can connect with the client. This second factor is the productivity mindset, voiced in his frustration. He thought he wrote a good paper and deserved to do better on the first attempt. But now that he has to make revisions, he is displeased.

Following a standard rapport building model such as Susan Phillips’ “Connect, Inquire, Act” that is taught in many writing center training courses, the tutor has now completed step one. Instead of interrogating those global concerns further and opening the floor to educating the writer that the writing center can help with those concerns, she moves on to “Inquire.” When she asks him what his agenda is for the session, he states that he wants to work only on grammar:

W: Uhm, so, this like it’s like a finished paper you know it’s I’m just looking for, like, kinda feedback and grammatical stuff ’cause I am like king of run on sentences so

T: Mhm, okay, cool. Uhm have you been to the writing center before?

W: Yeah multiple times.

With the small self-deprecating joke about being the “king of run-on sentences,” the writer turns a low order concern into the focus of the session. Despite having gone to the writing center multiple times that year, the writer has an inclination toward a productivity mindset and a lack of educated agency. First, if he hasn’t been educated on the goals of the writing center as a place to grow as a writer at all stages, perhaps he sees the center as remedial or only for editing purposes. He seems eager to insist that the paper is complete despite the issues he raised previously. If the tutor had recognized and addressed these issues earlier, the agenda could have looked much different, and he may have walked away with a better understanding of writing center work.

The next section where educated writer’s agency and productivity collide is much later in the session when the tutor attempts to make a shift from addressing grammatical concerns to discussing his argument structure:

W: Yeah, ’cause I usually conclude with my own ideas, so it’s probably…

T: Uhm, so yeah, for the introduction, maybe in the first, uhm, and you could also do that by, like, kind of personally, or putting your own op-, uh, analyzing the quotes, and putting your own opinion after hat right there. Uhm.

W: Yeah, the other problem is 1500 words, and I am at 18 here, 1800. Yeah, and you’re like, it’s really difficult to do all, like, what he’s asking for, and, you know, 1500.

T: Uhm. Do you want me to look and see where you can cut it or?

W: No, cause my ***, he didn’t take off points, [and my *** was like 2000 words, so.

T: O.K. Alright, uhm, *** sources that are well understood. I think you did that. Uhm, you did that ***. (reading quietly) You did that a little bit. Uhm.

The session moves quickly when the tutor corrects the writer’s grammar, and the writer in turn corrects the tutor’s pronunciation of ancient Roman and Greek names. Productivity is associated with time and how quickly the writer can make the most edits. The writer is so focused on productivity that the moment the tutor makes a move to address another implicit expression of need (his high word count and an inconsistency between introduction and conclusion paragraphs), the writer repeatedly rejects her suggestion. This could have been another opportunity to educate him on the goals of the center, particularly emphasizing that time spent in the center is for the writer and their paper. Instead, she allows herself to be dismissed, and becomes hesitant with her recommendations, evidenced by the number of “um”s, “uh”s, and pauses for the remainder of the session.

The take away from this session is that its effectiveness was likely compromised partially because the tutor allowed the writer’s productivity mindset to interfere with his educated writer’s agency. The other aspect was that she either did not pick up on his implicit expressions of need or felt conflicted about addressing his implicit needs and his explicit agenda. As a result, they could not get to the root of the structural issues in his paper, and the session suffered.

Recommendations

The long reaching social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic make Care-Based Inquiry a much more urgent pursuit for tutors, administrators and institutions. As we return to our physical centers from a virtual learning environment, we must consider the impacts of online learning etiquette and a loss of consistent social connection. Still, this article is about more than just returning to our previous social rituals; it is about knowing how to move forward by understanding what issues have been raised in the past. One of the biggest challenges that we still face is renegotiating care as a relational consciousness because we are still thinking about care in relation to our bodies and those of others. While many of us are happy to regain our social spaces, we must recognize that many still have to make hard decisions because their physical health is still at risk. Therefore, we recognize that the locus of care has shifted from the individual space that one inhabits back to a consciousness of the space we exist in with other bodies. Without compassionately existing with the client in their own physical and mental spaces, care will suffer.

As a result, one of our main goals for this project is to offer recommendations for writing centers, writing center directors, and individual tutors to promote an environment of optimal care and accessibility. Optimal care as a tenant of CBI is reached when there is a balance between care and productivity, so tutors can comfortably set boundaries that care for and protect both themselves and the writers. This is achieved partially by aligning agendas from the beginning of the conversation through education and, furthermore, by ensuring mutual collaboration to improve the quality of writing center sessions for all participants. To best describe this process, we have broken our recommendations down into three sections beginning with our recommendations for tutors in the center. We conclude with our recommendations for writing center staff and institutions and expanding the conversation into other possible avenues of further research.

Recommendations for Tutors for Personal Practice:

Reframe the standard rapport building from just the first five minutes of a session into a fluid practice: “Connecting to Inquire, Inquiring to Act”

Align the client’s agenda with your understanding of their needs by asking questions and maintaining Educated Writer’s Agency

It is also important to inform writers about the purposes and limitations of a writing center session as early as possible. Not everyone has the opportunity to get as close to writing theory as do trained writing tutors, or consistently to engage in intensive revision as tutors do through employment. It is essential to take steps to empathetically connect with the writer to the best of the tutor’s ability by intentionally and respectfully entering that headspace. We must meet the client where they are – tutor and writer with one another with the paper.

Explicitly communicate boundaries during sessions to create a precedent of reciprocal care

The first five to ten minutes of a session are essential for the writer to understand the tutor and for the tutor to understand the beginning of the context that they operate in with the writer. They should continue to build this context as the session unfolds to extend care across the session. To this end, slowing down and taking the time to conscientiously practice CBI is essential. Tutors must explicitly communicate to the writer that the time spent in the writing center is ultimately for them, so they do not have to rush.

Use CBI to negotiate conflict respectfully with “Step Back, Reframe, Reenter”

Pay attention to implicit and explicit expressions of need in order to care for the whole writer, not just the piece of writing

Recommendations for Writing Center Directors and Staff:

- Reframe tutor training curriculum to teach CBI as rapport-building and teach boundary-setting

Practicing CBI in order to align agendas early on can reduce tutor burnout. A better informed writer is less likely to put a tutor in an uncomfortable position or trespass their boundaries by asking them to perform tasks that could violate academic integrity. That said, instruction for tutors on how to set boundaries and communicate the possibilities of each unique writing center is an important addition to any tutor training curriculum.

- Invite tutoring staff to participate in decisions about their writing center and engage the feedback they give about their workspaces to uphold Educated Tutor’s Agency.

Actively including tutors in conversations about their writing centers, and actively listening to their feedback is the way to practice educated agency between the writing center administration and its tutors. When tutors are actively participating in how their centers are run, that open line of communication helps to preserve peerness at all levels in the center. Ultimately, tutors cannot perform CBI if they are not being cared for by their administration.

Recommendations for Institutions to Support Their Writing Centers:

- Begin with first year and transitional courses to care for college writer

Writing fellows or liaisons can be paired with entry level and discipline-specific writing courses requirements. They introduce students to the work of the writing center by facilitating extra writing support in the form of peer reviews, individual planning sessions, and working with professors individually to provide student-centered feedback on prompts and writing processes. They also help to recruit new tutors from these courses, because these students tend to have a better concept of writing center work having seen it first hand. Furthermore, tour guides should be able to give an accurate representation of what college writing and conversation looks like, so that prospective students are already attuned to the campus philosophy of teaching, learning and collaborating on writing. There is no better ambassador for this goal than the writing center.

- Collaborate with writing centers to create an accurate perception of the writing center and care for the workers who support incoming and current students

If the writing center is caring for the institution’s writers, then the institution can care for the writing center by making sure that their information and marketing tools are up to date and accurate. Furthermore, it is important for institutional representatives to engage in conversations to counteract the perception of writing centers as purely remedial and, instead, a place to engage in undergraduate scholarly conversation. All academic communities are involved in peer review and feedback in some way. The sooner students are involved in an active academic conversation that respects all participants, the better citizens and agents of inclusivity they will become in their academic and professional careers.

Fig. 8. Anecdote 3: The Golden Session.

To end, we will share one final story from Anna’s experience about a session in which care-based inquiry was successful. In this session, the writer was very stressed about a long history paper. The writer brought in the professor’s feedback that contained some distressing comments, and the paper was due the next day. She had a little blue sticky note that said “thesis” and “conclusion,” which she identified as her main concerns, but she was talking quickly and seemed visibly anxious. Anna decided to slow down since there was clearly something else going on. No one comes to the writing center that stressed about a thesis and conclusion.

Before diving into her paper, Anna asked her about the course, the kinds of conversations she was having in class and in office hours with her professor, and then her background and writing process. It turns out that this student was a first-year student in an upper-level class outside of her intended major with no explicit guidance on writing conventions in history. Little buzzer lights went off for Anna because it felt like she had found the real source of the student’s anxiety about this paper.

Anna talked to her about different approaches that they could take and then suggested that they reverse outline the argument to look for a thesis, and then talk about further implications for a conclusion. Anna acknowledged the writer’s frustration with not knowing the conventions of a historiography and asked again if the thesis and conclusion were the only things about which the professor offered feedback. She stopped looking through her notes and said, “Actually, yeah let me show you the email that he sent me. Can we look through it together?”

It turns out the professor was very clear with this student, stating that she had “failed to organize [her essay] in a coherent style” and that the paper had multiple organizational issues. After the writer had corrected these things, she was able to target the thesis and conclusion. After reviewing this email, the priorities of the session switched immediately.

The pair reverse outlined the paper for argument, transitions, and a thesis, and even though they didn’t have time to brainstorm the conclusion together, Anna gave her a heuristic to think about it later that day. Even though they didn’t get to the writer’s entire agenda, it is important to note that she visibly relaxed throughout the session and appeared confident and satisfied with the outcome. If Anna had not taken the time to connect with her throughout the session with the care-based inquiry model, they would not have had such a good session. It likely would have resulted in frustration and conflict since they had different agendas at the beginning.

Conclusion

In the wake of the pandemic, tutors’ and writers’ views of productivity and care are being challenged. During the pandemic in an online, physically-distanced setting, writers were expected to produce the same quality work with fewer resources and less certainty about the future. Before the pandemic, writers often worried about being productive— that is, the good use of time measured by output. However, with fewer resources and less support in a fully virtual environment, those definitions had to change. Care looked much different as well, because the pandemic deepened gender inequities in care systems such as the home. Both of these major social shifts are a source of trauma that writers and tutors are still navigating and healing from. Care-Based Inquiry is a theory of tutoring which derives directly from the COVID pandemic, in which writing centers consistently had to rethink issues of identities, systems of care, and views of productivity.

We view the writing center as a care system, and while we are constantly asking how we can care for writers and their identities when they come to the center, we also need to acknowledge that tutors are still healing as well. As such, they should be entitled to a similar level of respect and care. This brings us to two fundamental questions: firstly, how can we best care for ourselves as tutors while also caring for our clients and their needs, but not at the expense of their papers? And secondly, what might Educated Agency look like for tutors within their institutions? If the writing center is not only a care system, but a gender-responsive care system, then CBI must be executed by administration for the tutors as well. Tutors must be actively involved in running their work spaces, given a voice in decision making processes, and encouraged to be in open communication with center directors. When peerness is preserved at the administrative level as well as at the service level, CBI can become the framework for a trauma informed, gender-responsive care system. This means that writing centers take a step toward effectively thinking about productivity and de-gendering care models in the writing center so that efficiency and emotional vulnerability do not harm the well being of the tutor or writer.

Works Cited

Denny, Harry C. “Facing Sex and Gender in the Writing Center” in Facing the Center: Toward Identity Politics of One-to-One Tutoring. Utah State UP, 2010, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt4cgqnv.

Lauren Fitzgerald and Melissa Ianetta. The Oxford Guide for Writing Tutors: Practice and

Research. New York: Oxford UP, 2015.

Held, Virginia. “The Ethics of Care as Moral Theory.” The Ethics of Care: Personal, Political, and Global, New York, 2005, pp. 9-28, doi-org.dickinson.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/0195180992.003.0002.

Miley, Michelle. “Feminist Mothering: A Theory/Practice for Writing Center Administration.” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 41, no. 1-2, 2016, pp. 17-24, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v41/41.1-2.pdf.

Phillips, Susan, and Patricia Brenner. The Crisis of Care: Affirming and Restoring Caring practices in the Helping Professions. Georgetown UP, 1994.

Rafoth, Ben, et al. “Sex in the Center: Gender Differences in Tutorial Interactions.” The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 24, no. 3, 1999, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v24/24.3.pdf.

Spitzer-Hanks, Thomas. “On ‘feminized space’ in the Writing Center.’ Praxis Blog, 2016, http://www.praxisuwc.com/praxis-blog/2016/4/13/on-feminized-space-in-the-writing-center.

“The Norman M. Eberly Multilingual Writing Center.” Dickinson College, https://www.dickinson.edu/info/20158/writing_program/2829/the_norman_m_eberly_multilingual_writing_center.

Trachsel, Mary. “Nurturant Ethics and Academic Ideals: Convergence in the Writing Center.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 16, no. 2, 1995, pp. 24-45, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43441986.

Tronto, Joan C. “Redefining Democracy as Settling Disputes about Care Responsibilities.” Caring Democracy: Markets, Equality, and Justice, New York UP, New York, 2013, pp. 17–45, doi-org.dickinson.idm.oclc.org/10.18574/nyu/9780814770450.001.0001.

- Transcripts for all anecdotes ↵

- It is important to note that all of these sessions occurred before the COVID-19 pandemic, so they are not representative of the changes that may have occurred in the writing center since March 2020. ↵

- We recreated the audio recordings of several portions of several key sessions to accompany this article: to preserve the privacy of tutors and writers, we performed the voices of the participants in the sessions. ↵

- CBI aims to reframe a current rapport building model that is taught in the Oxford Guide for Writing Tutors is modeled after Susan Phillips’ description of caring professions. She describes “Connect, Inquire, Act” as the recommended method of beginning any kind of appointment centered care work (Phillips and Brenner). But we find this model to be limited because care and work are seen as discrete pieces of the session. ↵