5 The Loss of We: An Empirical Investigation of Synchronous and Asynchronous Tutoring Experience Before and During the Pandemic

Dana Driscoll and Andrew Yim

Indiana University of Pennsylvania

Asynchronous tutorials were a contested practice within writing centers, but with the pandemic, many writing centers began offering more asynchronous tutoring as a way to reach students virtually. From early debates about the usefulness of asynchronous tutoring from Michael Spooner and Eric Crump in 1994 in WLN, to more present day conversations (Camarillo, Denton, Fleming, Neaderhiser and Wolfe), discussions about asynchronous tutoring often depict a problematic binary. Writing centers often choose not to employ asynchronous tutorials because these tutorials appear to be at odds with writing centers’ values of collaboration, conversation, and one-to-one interaction (Bruffee; Lunsford). Stephen Neaderhiser and Joanna Wolfe’s research through the Writing Centers Research Project demonstrated that a vast majority of writing center practitioners believe that “physicality is key to writing center relationships” (66) and, often, asynchronous tutorials appear less “relationship oriented” than face-to-face or synchronous tutoring. James A. Inman and Donna Sewell, Beth L. Hewett, and Kathryn Denton have all argued that the challenges with asynchronous tutoring are often ideological. One way of moving beyond binary debates is exploring the nuances of asynchronous tutoring by providing replicable, aggregable, and data-supported research (RAD) in writing center settings, as described by Dana Driscoll and Sherry Wynn Perdue.

Such RAD research that examines the efficacy of asynchronous tutorials is starting to emerge, although much more work is needed, particularly mixed methods work on a larger scale. Denton’s work has demonstrated that many different kinds of students can benefit from asynchronous feedback. Neaderhiser and Wolfe described that while students found asynchronous tutorials beneficial, these tutorials may be more impersonal; therefore, tutors must work to create more personal interactions asynchronously. Asynchronous tutorials have been found to meaningfully support certain populations that frequently use writing center services, including multilingual writers (Keown), students with disabilities (Daniels and Babcock), and neurodiverse students (Cherney). Most recently, asynchronous tutorials can support an antiracist approach, as diverse students may find asynchronous tutorials more accessible and helpful (Camarillo). All of the above research offers writing center practitioners some insight into how to create effective asynchronous sessions for a range of students and their needs, but we recognize that considerable challenges remain.

Our writing center, at Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP), ascribed to the “synchronous is superior” philosophy and did not offer any asynchronous tutorials prior to the global pandemic. Everything changed with the advent of COVID-19 when we were faced with a choice: continue to privilege tutoring only through conversation (synchronous), or expand our services with asynchronous tutoring. Asynchronous tutoring would allow us to reach a number of rural students without access to high-speed internet[1], a challenge that continued to impact educational services and courses for many undergraduate students throughout the pandemic. We also had students who were living in areas without regular access to the internet or electricity (such as war-torn areas globally) and still other students who would benefit from asynchronous services (such as those who were deaf or neurodiverse). Our own unique circumstance–shifting into offering hundreds of asynchronous tutorials after doing none before the pandemic–allowed us to have a natural quasi-experiment (e.g. two different comparison groups before and after). Thus, our study examines how our writing center moved from a primarily in-person and online synchronous service to a virtual hybrid service offering both synchronous and asynchronous tutorials.

The purpose of this study is to answer two research questions: What are the differences between synchronous and asynchronous modalities, as present through our pre- and during-pandemic session reports? And second, what do our tutors recognize as valuable and challenging in the shift in tutoring modalities? Through qualitative interviews with ten tutors and through an analysis of over 2000 pre-pandemic and during-pandemic session reports, we offer a mixed methods analysis of how providing asynchronous tutorials fundamentally shifted our practices. Through this study, we also offer insight into the nature of asynchronous tutorials and the challenges they present, as well as suggestions for writing centers that are considering implementing asynchronous tutorials.

Context and Purpose

The Jones White Writing Center is located in rural Western Pennsylvania at a public, doctoral-granting institution serving both undergraduate and graduate students. A large number of our undergraduates are from rural areas, while a large number of our graduate students are working professionals and/or international multilingual writers. Our writing center offers a comprehensive range of services including tutorials, workshops for both graduate and undergraduate students, dissertation writing boot camps, and graduate writing groups. Prior to the global pandemic, our writing center did not offer asynchronous tutorials of any kind, and even our synchronous online tutorial service was fairly limited (representing less than 10% of 4000 annual tutorials). Because we serve a largely residential undergraduate population with over 50% of our students from rural areas without access to high-speed internet, at the start of the pandemic we made the decision to allow both video tutorials (through WCOnline and/or Zoom) and asynchronous tutorials (through WCOnline). While 100% of our tutorials were synchronous and 90% were face-to-face before the pandemic, after the pandemic started, nearly 50% of our tutorials were asynchronous, offering a fundamental shift in the way that students used our service and how we tutored. This shift offered us an opportunity to engage in quasi-experimental research to explore both how our own practices and tutorial-focus changed as we moved into adopted asynchronous pedagogy and also what those shifts meant for our tutors and students. Table 1 offers a breakdown of the differences in our service modalities during the six months pre- and post-pandemic.

Table 1

Comparison of Tutorial Modalities Pre- and Post-COVID-19[2]

| Dates | Face-to-Face | Synchronous Online Tutorials | Asynchronous Online Tutorials | Total |

| Pre-COVID: 8/26/2019-3/6/2020 | 1732 | 137 | 0 | 1869 |

| Post-COVID: 3/16/2020-8/7/2020 | 0 | 168 | 218 | 386 |

In order to transition to online tutoring in March 2020, tutors were given a three-hour training in synchronous and asynchronous pedagogy, drawing on the best practices in the field, including work by Denton and Joshua Weirick et al. Tutors also had two hour-long training sessions in April and May of 2020 where we read student texts and discussed approaches to asynchronous tutoring. All tutors receive CRLA 1 tutor training certification during their first year of tutoring; thus, at the time of the transition, all tutors had a minimum of five months of tutoring experience and had completed their CRLA-1 training. We have included our lesson plan and handout from the March 2020 training in the Appendix. Our topics included attending to tone, offering feedback in friendly and helpful ways, focusing on higher order concerns, working with diverse writers, and building rapport and connection with writers asynchronously.… our training focused on building tutors’ expertise in offering asynchronous feedback and also encouraged tutors to continue to work to build connections. Tutors practiced offering feedback on sample student work, discussed sample scenarios, and considered the benefits and challenges of asynchronous tutoring in an online group setting. Additionally, after we made the transition, tutors were offered feedback from the assistant director and director on their asynchronous tutorials. In other words, our training focused on building tutors’ expertise in offering asynchronous feedback and also encouraged tutors to continue to work to build connections asynchronously.

Table 2

Comparison of Graduate and Undergraduate Students’ Usage Patterns Pre- and Post-COVID-19

| Dates | Graduate | Undergraduate |

|

Pre-COVID: 8/26/2019-3/6/2020 |

505 students- 27.0% | 1364 students- 72.9% |

|

Post-COVID: 3/16/2020 – 8/7/2020 |

234 students- 60.6% | 152 students- 39.4% |

Table 2 compares the pre- and post-COVID-19 usage patterns for our graduate and undergraduate students. Our pre-COVID-19 numbers were consistent with other years of operation. However, post-pandemic, our undergraduate usage declined considerably while our graduate student usage slightly increased. We believe our graduate usage increased because the asynchronous tutorials were more accessible to graduate students (particularly for our working professional populations).

Methods

In this IRB-approved mixed-methods study, we used a combination of interviews conducted with ten tutors who had experienced pre-and post-pandemic tutorials. Additionally, we conducted a computational analysis of 2225 pre- and during-pandemic session reports, specifically examining face-to-face, synchronous, and asynchronous tutoring. We examined the following questions:

- What are the differences between synchronous and asynchronous modalities, as present through our pre- and during-pandemic session reports?

- What do our tutors recognize as valuable and challenging in the shift in tutoring modalities?

The pre-and post-session reports include all the sessions we conducted in the time period specified in the study. Tutors who were interviewed had experience tutoring both before and during the pandemic.

Session Report Computational Analysis

To analyze session reports (for the six months pre- and post-pandemic), we employed statistical and computational linguistic techniques, inspired by Genie N. Giaimo et al.’s work on computational analysis of session notes. We used SPSS to calculate descriptive statistics on our reports and usage. We used AntConc (computational linguistics software) to identify and examine patterns in our session reports, including the topics tutors worked on and key repeating terms in the post-session recaps. These two quantitative approaches allow us to understand the broader picture of words and combinations of words that emerged from our session reports based on the type of group (graduate and undergraduate) and the different modalities (in-person, synchronous online, and asynchronous online). By using both direct (session reports) and indirect (interviews) measures, we offer insights into how changing the modality of our sessions changed the nature of our tutoring pedagogy.

Interviews

All 23 tutors on staff in spring and fall of 2020 were contacted via email and asked if they would be willing to participate in an interview. Ten tutors (43.5%) agreed to be interviewed. Each of the ten tutors had worked for at least one semester at the writing center prior to the pandemic and were able to describe experiences tutoring synchronously and asynchronously; three of our ten tutors were undergraduate students and seven were graduate students. Once tutors agreed to the interview, Andrew interviewed them for 30-60 minutes via Zoom. Interviews covered tutoring experiences both before and during the pandemic, including memorable tutorials, student expectations, and experiences with asynchronous, synchronous, and face-to-face tutoring. Questions from the interview are included in the Appendix.

Interviews were professionally transcribed, de-identified, and analyzed by both authors using several rounds of thematic analysis techniques (as per Saldaña). Specifically, we examined how tutors discussed and compared asynchronous tutoring practices, their positive and negative views of such practices, and their adaptations, which allowed us to identify three major themes (transition, space of center, and model preference). After completing our computational analysis, we also examined these interviews in light of our findings from the computational analysis to understand tutors’ beliefs about the shift in modalities.

Limitations of this study include the fact that our study represents only one institution and that we are limited to interviews and post-session reports for a one-year comparison period.

Results: Computational Analysis

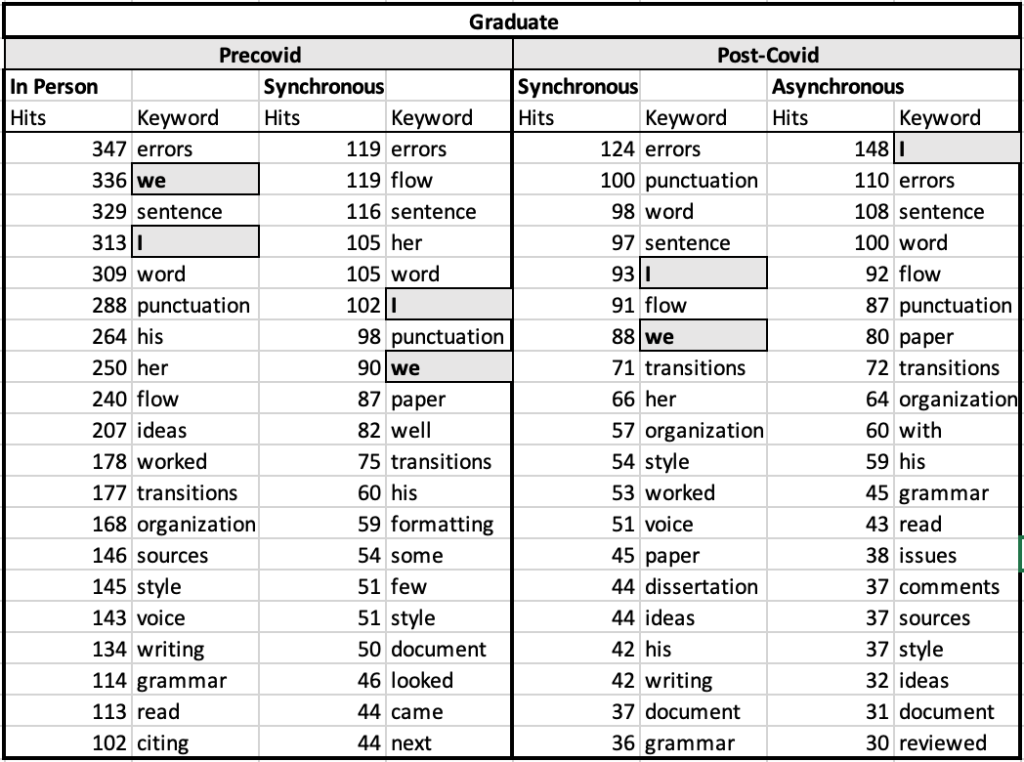

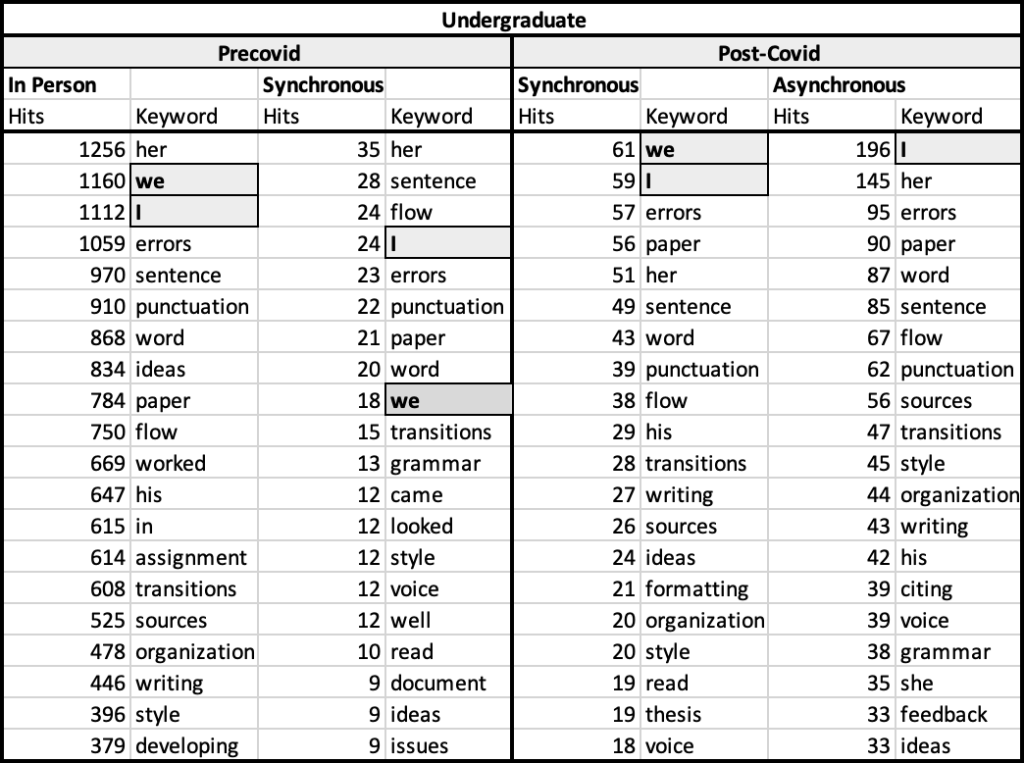

Our post-session reports have two open-ended categories that tutors fill out—a short, open-ended statement that describes the writing topics covered in the session and a session recap that is sent to instructors and kept for our records. We split these session reports into the type of tutorial, pre-and post-COVID-19, and by graduate and undergraduate writers. From this analysis, we omitted articles and prepositions (which always show up high in any computational analysis). Figures 1 and 2 offer the top keywords for each kind of session, how many times the keyword appeared, and separate undergraduate and graduate data (which are two distinct groups at our institution).

As visible from Figures 2 and 3, our in-person and online synchronous sessions pre-COVID-19 had similar top word hits: errors, flow, punctuation, sentence. We also note the high prominence of “we” and “I” pre-COVID-19, both in-person and online synchronously. Post-COVID-19 synchronous online sessions are almost identical in terms of the material covered and percentage of frequency from the synchronous post-COVID-19 sessions. The biggest change at both the undergraduate and graduate levels was the loss of “we.” Not only does “we” not show up in the top 20, it does not show up in the top 100 words for asynchronous tutorials.

To see what this looked like in practice, we compared several session reports pre-and post-pandemic with the same tutor and students at the graduate and undergraduate level. We note that all names provided are pseudonyms.

These two examples are particularly telling because they come from the same tutor and students, who met both pre- and post-pandemic in online sessions, thus allowing us to illustrate the shift that was present throughout the data. When the writer and tutor are synchronous, we see aspects of a two-way conversation present. When the same tutor-student pair are asynchronous, the loss of that conversation and interaction is evident. As a result, we see the tutor focusing on what they did and the suggestions they make that are passed onto the student.

Results: Interviews

Three major themes appeared in our data including Space of Center, Model Preference, and Transition (in-person to online). Our interviews provide insight into our examination of the loss of “we” in our sessions and tutors’ perspectives on the nature of our shift to asynchronous tutorials.

Prior to the pandemic, our tutors viewed the writing center as a space for collaboration and community with both tutors and students, something that our entire staff worked hard to facilitate in our writing center. This community space was true for both graduate and undergraduate students, who used our services primarily in person. The “Space of Center” theme emerges in our data, which ties to the value of the physicality of the community of the writing center. As described in all ten interviews, tutors ensured that writers felt comfortable coming to the writing center and they all discussed specific ways they collaborated with student writers in our physical space. One tutor reflected about how they liked directly collaborating with students because “[tutors] should co-build with them. So, we should have worked together with them…or helped them find their recurring problems.” Another tutor mentioned working with writers multiple times throughout the semester in-person and reported that “[seeing] the growth in their confidence as well as the writing…are really fulfilling.” In addition, eight of the ten tutors we interviewed specifically characterized the physical writing center as a collaborative and highly engaging space, both for interacting with other tutors and writers. For example, one tutor highlighted that having all these tutors in the space helped “build a lot of connections and friendships that way” while another noted how “we created our own little family.” Our writing center for these tutors was a strong community environment where tutors had friendship, emotional support, mentorship, and writing support.

All ten tutors noted that after the pandemic began they missed being able to directly collaborate with each other and with writers on their ideas, which ties to Model Preference and Transition (in-person to online). Even though our tutors indicate success in their new online tutoring roles, all ten tutors noted their preference for synchronous and face-to-face tutorials. As one tutor noted, “The way I do my consultations, I also learn a lot from my clients.” Another tutor noted, “I am not a big fan of the asynchronous appointments just because I prefer to actively talk to the student I’m working with and I just feel like I can give them stronger feedback that way.” … the inclusion of “we” pre-pandemic can account for how writing center tutors defined collaboration and interpersonal interaction as being able to directly see and talk to their writers and other tutors in a warm and welcoming environment.Thus, the inclusion of “we” pre-pandemic can account for how writing center tutors defined collaboration and interpersonal interaction as being able to directly see and talk to their writers and other tutors in a warm and welcoming environment.

Further, the asynchronous appointments created challenges regarding negotiating goals of the session, setting the agenda, and determining what is accomplished, also tied to our theme of Transition (in person and online). Asynchronous tutorials required tutors to take more direct responsibility for setting the direction and boundaries and in making the exact decisions for the writing assignment. Even though students are required to fill out an intake form, they may leave very brief answers, which do not provide the tutor with deep insight into the student’s needs. One tutor notes,

“It was a little frustrating at times because I would I guess start reading the asynchronous…then I would go, did they mean this? Or do they mean this? And like the student wasn’t there to ask. So, I had to leave a comment saying, I think you mean this, but I’m not sure. And then it’s like, I hope the student then understands what I’m commenting to them.” One tutor had noted that students would ask “will you look at this and tell me if it sounds good…which is [way] too vague when you’re doing asynchronous because then they’re not even there to tell you [what they are] worried about specifically…”

Tutors also noted the challenge of when either graduate or undergraduate students ask for “grammar” support without being able to clarify: one notes that “students would say that [their] grammar needs to be fixed” and “because ‘grammar’ is so vague, there’s so many different things in that we can kind of break it apart and talk about that.”

Our tutors did see some positive benefits with asynchronous appointments. One tutor had noted that because they have social anxiety, “this is sort of like combating [social anxiety] a little because it gives me like ahead of time…it’s just, it’s easier for me to plan it out and not get as anxious.” Another tutor noted that they supported the writing center’s asynchronous appointments because

“even though there are times where like the asynchronous is troubling, it does provide the students with, like more access to the writing center because I knew a lot of my friends actually are now able to submit their papers when they weren’t able to before, because they just taking too many credits.”

Several tutors also noted that asynchronous tutorials turned out to be their favorite kind of tutorial. Ultimately, the incorporation of the asynchronous model as a tutoring approach not only gave rise to the “I” in asynchronous appointments but more importantly, redefined what collaboration and interpersonal interaction meant within a tutoring session.

Discussion

COVID-19 allowed for a quasi-experiment to take place in our writing center, an experiment that allowed us to see what changes took place in our session reports and in our own tutoring practices when we shifted to fully online tutoring and added an asynchronous tutoring modality. As we examine the emergency decision to offer asynchronous tutorials to increase access for our students, we also recognize the implications of this choice. In our ongoing training and in the Slack Channel we set up for regular interactions during the lockdown, we attempted to facilitate a community of tutors, and much of our ongoing training during the pandemic focused on how to rebuild the “we” in our sessions and in our writing center. This included both community-oriented activities for tutors and also ongoing professional development on how to build in more collaboration in asynchronous tutoring.

What we have come to understand through this study is that asynchronous tutorials do assist students in meaningful ways, but they require a different kind of mentality, focus, and set of expectations on behalf of the tutors. And regardless of how much training we offer tutors, the loss of “we” seems to be a part of that process, at least for the kind of sessions we offered before the pandemic and the ways in which sessions are reported. For example, in the sample session reports that we evaluated, the online synchronous sessions write ups offered insights into the collaboration and conversation between the tutor and writer whereas the asynchronous reports demonstrated more of a unidirectional movement of conversation from tutor to student. We see this change reflected in the tutor interviews as the tutors had reflected this new shift toward “I”– some felt that they could no longer converse with the student directly and had to give feedback based on the students’ written requests and the assignment prompt, if attached. Much of the “loss of we” had to do with the vagueness of student responses (e.g., “see if the paper sounds good” or “help me with my grammar and formatting”) which were not able to be negotiated, and which continued to happen despite our best efforts to collect information from students prior to the tutorial. We found this issue to be true for both our graduate and undergraduate populations, and since conducting our research, have made changes to our forms to ensure that we are asking as specific a set of questions as possible.

One of the underlying questions we ask is: what does “we” mean to writing centers and why is that loss so striking? “We” goes to the heart of writing center work, to Lunsford’s discussion of collaboration and Bruffee’s conversations of humankind, but also to our ideologies about what makes a good writing center tutorial. And while we recognize that “we” is an ideal, it is not always a reasonable reality for our work. That is, writing centers must balance our ideal notion of a session where “we” is in the center of our work with meeting student needs: meeting rural students who do not have access to high-speed internet; meeting international students who are in countries without stable internet or that are undergoing tumultuous political instability; meeting non-traditional students who are unable to schedule appointments during our open hours; meeting our neurodiverse writers who may prefer less interaction; and meeting working parents with limited childcare.…Is there a way to keep the “we” and offer asynchronous tutorials to better meet student needs? We also recognize that even face-to-face sessions can struggle with “we,” such as the reluctant writer or the writer who is required to come to the writing center. The question that we are left with is: is there a way to keep the “we” and offer asynchronous tutorials to better meet student needs?

As our university returned to in-person instruction in fall 2021 and we had completed our research, our writing center staff continued to explore the issue of continuing to offer asynchronous tutorials. Dana (the Director) polled the tutors to ask about their preference to keep asynchronous tutoring. Despite the challenges outlined here, tutors overwhelmingly voted to keep asynchronous sessions, as they recognized that many writers could benefit from them and cited many examples of effective sessions. Our entire staff weighed the pros and cons and decided that asynchronous sessions would become part of our center’s regular practice–but in doing so, we had to carefully attend to the challenges of asynchronous tutorials: continue to assess them, talk through them, and develop a set of best practices. Anecdotally, we’ve also noted that the “loss” seems to be less prevalent in the time since we conducted our initial study and as new tutors are brought into our training involving all three modalities. We have now operated over four semesters with asynchronous tutoring as one of our three modalities, with about 40% of our present staff being hired and trained to use all three in a non-emergency setting. Thus, what seemed to be a distinct loss due to the emergency shift online has gradually become part of our regular practices, and discussion and the discourse around “loss” has been reduced but is never fully absent.

Thus, as we move forward as a center, we are now exploring a number of new directions with asynchronous tutorials. We share these here with the hopes that they will be useful to other writing centers who are looking to incorporate asynchronous tutoring:

Support tutors in facilitating the “we” and collaborative elements in asynchronous tutorials.

We identify several facets of this work. First, this includes encouraging students to seek more interaction such as to schedule a follow-up online or face-to-face session after an asynchronous session and/or encouraging students to respond to the session with additional questions. This approach has been met with success, particularly among our international student population. We’ve also worked with first-year writing faculty to specify which kinds of tutorials will be more helpful for first-year students. To help address the fundamental shift to asynchronous tutorials, we are also offering ongoing professional development workshops to offer tutors chances to reflect and practice on how to provide comments asynchronously. After conducting this research, we made a number of changes to the intake form to encourage students to share more specifics about their own agendas for the session, including setting clear and specific goals for tutoring (see Appendix B).

Encourage students who would most benefit from asynchronous sessions to schedule them

In our advertising and intake forms, we now encourage students to select sessions based on their needs and the kinds of writing support they are requesting, and we provide a scaffolded system for making decisions on which kind of tutorial would be most appropriate. For example, an advanced graduate student who has worked with a tutor over a period of time has already established a “we” and can be encouraged to use asynchronous tutorials, while a first-year writer would be encouraged to schedule an in-person session. We have also worked with faculty and university advisors to educate them on our types of sessions so they can best direct students.

Align the expectations of “we” with the lived realities of students and student needs, particularly the need to be more flexible and adaptable during challenging times.

Part of our choice to keep the asynchronous sessions is rooted in the need to be more flexible and open to student needs and recognizing that some students—and tutors–work best in asynchronous tutorials. Thus, we continue to align our own expectations of what tutoring can accomplish by conducting ongoing assessment, examining the nature of our different tutorials, and checking in regularly with tutors on what is working and/or needs to be changed. As some of our work has changed, so too has our writing center practices become more accessible to introverted tutors, some of whom strongly prefer asynchronous sessions.

Adjust our own ideologies about collaboration and conversation.

Now that we have been working on training, assessing, and understanding asynchronous tutorials, our entire staff is invested in both recognizing benefits and challenges. This has allowed us to dig deeply and expand approaches espoused by Denton and Hewett. As a writing center, we continue to explore our own thoughts, experiences, and ideologies surrounding these.

Explore alternative technologies for sessions.

As part of our ongoing commitment to making asynchronous tutorials more collaborative and personable, we are now exploring non-text-based technologies, such as video casting or voice memos, as possibilities for asynchronous sessions. A body of research suggests that media-rich feedback may be more effective for asynchronous tutorials (Joni Boone and Susan Carlson, Fleming).

To those thinking about developing asynchronous tutoring, we point to a recent article by Tom Earles that offers a number of heuristics for considering asynchronous tutoring. We hope sharing our writing center’s story will help other writing centers explore the nuances in changing modalities as a core tutoring practice and see the benefit and possibilities in asynchronous tutoring sessions.

Works Cited

Boone, Joni, and Susan Carlson. “Paper Review Revolution: Screencasting Feedback for Developmental Writers.” NADE Digest vol. 5, no. 3, 2011, pp. 15-23, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1097602.pdf.

Bruffee, Kenneth A. “Collaborative Learning and the ‘Conversation of Mankind.” College English, vol. 46, no. 7, 1984, pp. 635–52, https://www.jstor.org/stable/376924.

Camarillo, Eric. “Cultivating Antiracism in Asynchronous Sessions.” South Central Writing Association Blog, 30 April 2020, https://writingcenter08.wixsite.com/scwcaconference/post/cultivating-antiracism-in-asynchronous-sessions. Accessed 14 July 2023.

Cherney, Kristeen. “Inclusion for the Isolated: An Exploration of Writing Tutoring Strategies for Students with ASD.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 14, no. 3, 2017, http://www.praxisuwc.com/kristeen-cherney-143.

Babcock, Rebecca Day, and Sharifa Daniels. Writing Centers and Disability. Fountainhead P, 2017.

Denton, Kathryn. “Beyond the Lore: A Case for Asynchronous Online Tutoring Research.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 36, no. 2, 2017, pp. 175-203, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44594855.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Sherry Wynn Perdue. “Theory, Lore, and More: An Analysis of RAD Research in The Writing Center Journal, 1980–2009.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 32, no. 2, 2012, pp. 11-39, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442391.

Earles, Tom. “How I learned to Stop Worrying and Love Asynchronous Online Tutoring.” Research in Online Literacy Education (ROLE), vol. 2, no. 2, 2020, http://www.roleolor.org/how-i-learned-to-stop-worrying-and-love-asynchronous-online-tutoring.html.

Fleming, Anne M. “Where Disability Justice Resides: Building Ethical Asynchronous Tutor Feedback Practices within the Center.” The Peer Review, vol. 4, no. 2, 2020, https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-4-2/where-disability-justice-resides-building-ethical-asynchronous-tutor-feedback-practices-within-the-center/.

Giaimo, Genie N., et al. “It’s All in the Notes: What Session Notes Can Tell Us About the Work of Writing Centers.” Journal of Writing Analytics, vol. 2, 2018, pp. 225-56, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/jwa/vol2/giaimo.pdf.

Hewett, Beth L. The Online Writing Conference: A Guide for Teachers and Tutors. Macmillan Higher Education, 2015.

Inman, James. A., and Donna Sewell, editors. Taking Flight with OWLs: Examining Electronic Writing Center Work. Routledge, 2020.

Keown, Kelvin. “A Big Cupboard: Developing a Tutor’s Manual of Model Asynchronous Feedback for Multilingual Writers.” Research in Online Literacy Education 2.2, 2019, http://www.roleolor.org/a-big-cupboard-developing-a-tutors-manual-of-model-asynchronous-feedback-for-multilingual-writers.html.

Lunsford, Andrea. “Collaboration, Control, and The Idea of a Writing Center.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 12, no. 1, 1991, pp. 3-10, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43441887.

Meinrath, Sascha, et al. “Broadband Availability and Access in Rural Pennsylvania.” Center for Rural Pennsylvania, 2019.

Neaderhiser, Stephen, and Joanna Wolfe. “Between Technological Endorsement and Resistance: The State of Online Writing Centers.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 29, no. 1, 2009, pp. 49–77, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442314.

Saldaña, Johnny. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. SAGE, 2021.

Spooner, Michael, and Crump, Eric. “A Dialogue about OWLing in the Writing Lab.” Writing Lab Newsletter, vol 18, no. 6, 1994, pp. 6-8, https://www.wlnjournal.org/archives/v18/18-6.pdf.

Weirick, Joshua., et al. “Writer L1/L2 Status and Asynchronous Online Writing Center Feedback: Consultant Response Patterns.” Learning Assistance Review, vol. 22, no. 2, 2017, pp. 9-38, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1154520.pdf.

- According to the Center for Rural Pennsylvania’s 2019 Broadband Accessibility study, over 800,000 Pennsylvanians, primarily in rural areas, do not have access to high speed internet. Only the state’s three urban areas have consistent access to 25 mpbs per second connections or higher. Many undergraduate students at IUP come from rural communities. ↵

- Because we switched data collection systems and changed our post-session report questions at the beginning of the Fall 2020 term, we are only able to offer comparison data for the academic year 2019-2020 for this analysis. However, in a typical year, our writing center remains busy during the summer months because we have many summer-only graduate and undergraduate programs and undergraduate students often use summers to take on general education courses, like first-year composition. Thus, in a typical non-COVID-19 year, we would see high student usage throughout the spring and summer months, making this time period comparable. From conversations among directors on our listservs and social media, nearly all writing centers experienced a large decline following the lockdowns and transition to online education. ↵