8 Remotely Sustaining Community and Enhancing Professional Development in a Writing and Communications Center during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Nikki Chasteen, Kelly Concannon, Kevin Dvorak, Eric Mason, and Janine Morris

Nova Southeastern University

With the sharp, unexpected increase in remote work during the pandemic, workplaces, including writing centers, have struggled to maintain professional and personal connections among their team members (Brooks-Gilles et al.). As the pandemic recedes, writing center practitioners should be mindful of what this period has taught us about developing and sustaining community among staff. Using the concept of a community of practice (CoP) as an organizing principle, we discuss how we redesigned daily operations to keep 70+ newly remote staff at the Nova Southeastern University (NSU) Writing and Communication Center (WCC) engaged with students, colleagues, and the center (see fig. 1 for a photo of the WCC).

CoPs have been defined by Etienne Wenger et al. as “groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly” (4). Such groups share a domain of interest, form a community through social interactions, and accomplish work via collective practices. In other words, a CoP is distinguished by its focus on knowing and learning, on improvement over time, and on the collective memory and activities through which community members “accumulate knowledge, [and] become informally bound by the value that they find in learning together” (Wenger et al. 4). We believe, as Anne Ellen Geller et al. note in their book The Everyday Writing Center: A Community of Practice that writing centers are excellent sites to explore how CoPs function due to how they position faculty and students as “learners on common ground” (7).

This essay reflects on our experience of learning to adjust to conditions during the pandemic, focusing on the CoP framework through three groups of initiatives: enhanced communication and virtual staff training; social justice, inclusivity, and mental/physical wellbeing; and social media and digital production (see fig. 2).

Overall, we call on readers to consider how our centers function as CoPs and the specific practices that work to sustain community regardless of modality and what these practices look like post-pandemic. Only through such reflection can we be responsive to the conditions our communities face and be thoughtful as we reshape our centers through practices that recognize the value of shared learning.

Our Writing Center as a Community of Practice

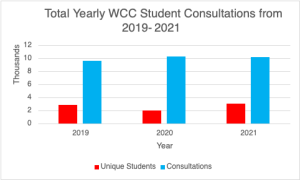

The NSU WCC serves approximately 20,000 students. It has a primary physical location on NSU’s main campus in Fort Lauderdale-Davie, Florida, but also serves students at seven regional campuses across the state and one campus in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Prior to the pandemic, about 80% of WCC consultations were in person, while 20% were conducted virtually via a synchronous platform; once the pandemic began, we transitioned to providing 100% of consultations synchronously online. Looking at our center in terms of the numbers of consultations, though, it might appear that not much has changed since March 2020, since the number of students and consultations have increased slightly (see table 1).

Table 1. Total Yearly WCC Student Consultations, 2019-2021.

| Year | # Unique Students | # Consultations |

| 2019 | 2,882 | 9,611 |

| 2020 | 2,948 | 10,296 |

| 2021 | 3,103 | 10,210 |

But the delivery and distribution of our services do not tell the whole story about the changes that have occurred. Pre-pandemic, our 70+ consultants did not simply deliver consultations to clients. They also engaged in a number of activities that supported our commitment to functioning as a CoP. Pre-pandemic, our center hosted internal-facing events (e.g., full staff trainings, movie nights, and staff potlucks) and external-facing events (e.g., Wikipedia edit-a-thons; Kinda Long Night Against Procrastination[1] and Biology Long Night Against Procrastination; and regional Tutor Collaboration Days) that engaged our staff, the NSU community, and the larger writing center community in Florida. While these events occasionally had synchronous online options for participation (e.g., GoToMeeting participation for northern Florida schools during Tutor Collaboration Days), our center’s community-building activities largely took place in person.

As we reflect on the changes our center has made, we see how our CoP moved beyond our reliance on in-person community building. Our fully remote transition was a new experience for us, reinforcing this shared sense of being learners within a CoP rather than being established experts. Shared experiences like these are especially important during periods of transition when communities of practice can “enable practitioners to take collective responsibility for managing the knowledge they need, recognizing that, given the proper structure, they are in the best position to do this” Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner). Recognizing the importance of learning together through shared experiences, the WCC leadership team led a coordinated effort to

- Establish a new organizational communication strategy to support a transition to training staff members into a remote work environment,

- Provide wellness activities and social-justice-oriented events to help staff members reduce stress, stay focused, and build community, and

- Redesign media that helped the WCC stay visible to students and faculty.

Without such intentional practices, our writing center, with its mainly one-to-one consultations and, during the pandemic, increasingly remote and online interactions, risked losing those interactions that make collective learning and growth possible.

Expanding our Domain through Organizational Communication Strategies

Not every social group or even workplace constitutes a CoP, since some groups share a set of concerns or preferences without engaging in the kinds of interactions that make such collective learning possible. It is true that writing center consultants, even when coming from a range of disciplines, share a commitment to helping others learn how to communicate more effectively. In their quest for helping clients become stronger communicators, our consultants meet the expectation that a CoP will have an “identity defined by a shared domain of interest” (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner). This does not mean each individual will know everything about communication in all situations. Rather, CoPs are marked by their interest in developing collective expertise. And our consultants understand that what we communicate to the university about our expertise matters. We do not want clients treating us as technicians who can fix their papers for them, or as subject matter experts who will correct the content of their work.

To some degree, what consultants needed to know changed with the pandemic. New training materials and policies were created to cover situations likely to arise in online sessions, and existing practices were re-evaluated to assess their continued relevance. Graduate Assistant Coordinators on our Education and Training team transitioned our normally asynchronous training modules and in-person mock sessions to a fully remote process. After gathering feedback from our summer 2020 undergraduate staff (approximately ten consultants), more interactive online materials were developed that focused on managing online sessions. Gathering consultant feedback is just one practice that highlights shared knowledge and adds to the collaborative environment the WCC seeks to foster. Once the feedback from consultants was incorporated into the revisions, the Education and Training team conducted usability tests with the summer staff in small groups over Zoom so the Graduate Assistant Coordinators could gain additional feedback from consultants completing the training modules in real time.

With such a large staff of undergraduate, graduate, and professional consultants, maintaining open communication is always a challenge. In an effort to keep our staff connected, we purchased a single-use license for the online meeting platform GoToMeeting. GoToMeeting provided us with a virtual lobby—our best course for mimicking the in-person lobby—in which consultants could hang out during their shifts when they were not conducting appointments via Zoom (see figure 3).

GoToMeeting provided an opportunity for consultants to have conversations ranging from real-time questions about APA citations to how to properly watch the Marvel Comic Universe movies in sequence. When peer consultants have appointments, they simply leave the GoToMeeting lobby and go into their institutional Zoom accounts to work one-to-one with students. Once the session concludes, they return to GoToMeeting where they can continue professional and personal discussions.

The revised training structure and the communication we encouraged through GoToMeeting enhanced the “shared domain of interest” important to our evolving CoP. Although consultants were all working remotely in a range of different environments, the expanded resources and spaces of our everyday interactions allowed everyone to engage in the long-term, interactive, and collective learning necessary to their work as consultants.

Maintaining a Community of Members: Addressing Consultant Wellbeing & Social Justice

One of the most significant components of a CoP is the community itself. According to Etienne Wenger-Trayner and Beverly Wenger-Trayner, members of a CoP “build relationships that enable them to learn from each other.” Most especially during the pandemic, when many dealt with isolation and a lack of physical connection (Brooks-Gilles et al.), the WCC actively worked to engage our community in activities related to well-being and mindfulness, and we promoted discussions and changed practices around race, social justice, and inclusivity.

During the pandemic, WCC leadership were concerned with consultant physical and emotional wellbeing. How consultants work within emotional sessions, feel supported, and are willing to share those perspectives speaks to the larger organizational structure. While the GoToMeeting lobby was meant to be a space where consultants could share any issues or incidents that came up, we wanted to give consultants other ways to take care of themselves and help each other.

Pre-pandemic, our pre-semester training included opportunities for consultants to discuss the emotional and mental stressors around tutoring. In person, consultants were encouraged to check in with Graduate Assistant Coordinators following sessions to discuss any difficult or emotional conversations that came up. Since our remote transition, we created activities to engage consultants remotely that cultivated connection and honest dialogue. Since so much of our prior team- and community-building happened informally in the WCC, we had to make purposeful choices to replicate those moments online.

New methods and new opportunities to engage in these processes were developed by the Education and Training team, who created a series of events intended to navigate the emotional labor of working online. Consultants who were already working during the events were blocked off from the schedule so they could attend during their shift. Off-shift consultants were invited to join in if they were available with the expectation that they would be paid for their time. For example, “coffee talks” allowed consultants to join a weekly Zoom session with no agenda, where they could voice concerns about sessions and have conversations about their lives outside of work. Because the “coffee talks” took place away from the GoToMeeting lobby, consultants were able to connect with one another on a more personal level. Further, we invited consultants to create habits of self-care and mindfulness through a series of Zoom-based yoga classes. These classes were designed for beginners, and consultants could choose whether to remain on or off camera. While we had talked about conducting yoga sessions pre-pandemic (especially since one of our Faculty Coordinators is a registered RYT® 200 yoga instructor), the pandemic provided a great opportunity to implement the classes so consultants could participate from wherever they were located. These events allowed for different approaches to mindfulness and self-care that focused attention on the physical and emotional well-being of our staff. Although we were cognizant of our consultants’ mental health, we quickly became aware of how the center’s online presence created new power structures that were exacerbated by students’ unequal access to technologies and workspaces (Brooks-Gilles, et al.). As our peer writing consultants began working remotely, we became privy to inequities that weren’t always apparent when students entered our campus spaces. Recognizing that not everyone was in a quiet space where cameras and microphones could be on, we gave our consultants and students the option for how to participate on Zoom; for example, they could choose to keep their cameras off or use the chat function.

In addition to addressing unequal power structures inherent in remote work, we engaged in practices that raised awareness of social justice in writing center work. This is significant insofar as the pandemic carried with it multiple racially charged moments of resistance and activism—many of which impacted how consultants relate to one another. As Bridget Draxler notes about her own writing center work: “I work hard to include, as much as I can, a bigger picture perspective of the work we do as ethical, political, and radical.” Our consultants engaged in civil discourse and social justice initiatives by participating in workshops that focused on their identities, power, and privileges; by promoting black-owned and historically marginalized businesses and authors on our social media platforms; by offering the option to add pronouns to our consultant bios; and by attending a monthly film series with a social justice theme. While we engaged in these activities in-person pre-pandemic, we were able to use software like Netflix Party to stream movies and Zoom to engage in conversations together from remote settings.

Acknowledging mental wellbeing, inclusivity, and social justice in writing centers through:

- “Coffee talks”

- Zoom-based yoga classes

- Flexible standards for Zoom participation

- Workshops on power and privilege

- Learning about and promoting black-owned businesses and authors

- Screening films with social justice themes

- Adding pronouns to consultant bios

Through these different activities related to social justice and consultant well-being, we worked to enhance the community foundation of our CoP by growing together and working to strengthen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us. If anything, these remote opportunities helped teach us that going forward we can take advantage of different modalities to engage our consultants who are offsite in ways that mirror the engagement we had physically in the center.

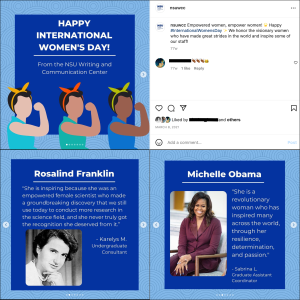

Developing a Repertoire of Practices through Media Production

Per Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, CoPs “are practitioners. They develop a shared repertoire of resources: experiences, stories, tools, ways of addressing recurring problems—in short a shared practice.” The WCC has two teams that practice production skills, one that focuses exclusively on social media and another that takes on specific media production projects. Both teams wanted NSU students to know that even though we were not physically on campus, we were still actively engaged and available to help them with any writing or communication assignment. We updated the WCC messaging on our website and social media to highlight our fully online presence (see our Instagram @nsuwcc for more posts). We also wanted those messages to highlight our staff to show the broader NSU community that we were experiencing the same feelings other students were, too. For example, our Social Media team crafted posts to celebrate days such as “National Work From Home Day” with a carousel of our consultants in their working spaces, and celebrated International Women’s Day with a series of images of inspiring women alongside quotes by WCC consultants of why those women are influential to them (see fig. 4).

The social media and production teams also shared WCC consultant stories by collaborating on crafting videos, blog posts, podcasts, newsletters, and Canvas modules. Engaging in these practices together took time and, as the diverse list of genres and modalities above highlights, required developing expertise in a range of tools and ecologies. While conducting sessions with students continued to be a solo experience, and the shared GoToMeeting lobby spaces provided informal interactions that were brief and oriented toward the present, media production provided our consultants with focused, sustained, and highly collaborative work through which professional skills and relationships could be strengthened.

Working on media production without being physically present in the WCC created opportunities as well as challenges. Opportunities such as increased collaboration and communication among the Social Media team afforded staff the ability to be involved in the creation of content while being at home. The social media and production teams relied on the messaging service Slack to share post drafts and get real-time feedback outside of meetings. Since students were now spending more time in online spaces (e.g., classes, keeping in touch with friends and family), there was an increased opportunity for our content to be viewed, liked, and shared. Other groups on and beyond campus were also interested in engaging with their own community members and enhancing communication efforts, and our staff found ways to support them as well. For instance, building on the skills learned creating the WCC’s podcast (https://anchor.fm/nsuwcc), Production team members volunteered to help the local Davie-Cooper City Chamber of Commerce develop their own podcast aimed at helping small businesses survive the pandemic.

While many of these communication projects often served the practical purpose of keeping consultants informed or enhancing their well-being, one of the most important functions of increased media production was the associated professional development. Since the WCC could no longer rely on posting marketing materials around campus to highlight our services, we relied more heavily on social media and other online content. Members of these teams now have a portfolio of content they can use to showcase skills they honed, such as content creation, audio and video editing, copywriting, graphic design, desktop publishing, and social media management. And these are not just individual skills, but skills that were honed collaboratively and discussed during weekly meetings and check-ins. Creating a social presence that connected the WCC to the larger NSU and Davie community necessitated a shared practice amongst team members–one that would continue beyond the pandemic.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we focus on the concrete decisions we made to maintain our writing center as a functioning CoP that valued learning and growth, even as we lost access to the physical spaces and practices through which we had previously achieved these. By focusing attention on shared knowledge making, collective well-being, and collaborative production practices, we feel the NSU WCC continued to thrive during a challenging time. By focusing attention on shared knowledge making, collective well-being, and collaborative production practices, we feel the NSU WCC continued to thrive during a challenging time. The pandemic interrupted many things about writing center operations, not the least of which were the narratives we tell about the work we do. As Jackie Grutsch McKinney reminds us, while the “writing center grand narrative is a cloth woven from various strands and strings to appear as a whole” there is value in testing “how easily it unravels under pressure” (6). The pandemic has presented both the challenge and the opportunity to reimagine the interactions through which writing centers function as CoPs.

At the NSU WCC, this work required flexibility and responsiveness to university, faculty, student, and consultant needs. It required embracing modalities and technologies that previously seemed to be at the “periphery of our work” (Grutsch McKinney 6). And it required empowering consultants to work together on projects that helped them build community through collective action and shared skill-building. These initiatives required extra effort on our part to establish and maintain, but we felt they were well worth doing. As we have moved forward, we have remained committed to enhancing our community of practice. We remain committed to being “learners on common ground” (Geller et al., 7), whether that ground be a shared physical space or virtual platform. We review, assess, and revise our education and training materials annually to meet the current needs of our consultants and students. Our workshops continue to be hybrid to offer the same opportunities to consultants working in the center and remotely. We support consultant mental health and wellbeing in both formal staff meetings and informally following sessions (in the center or through GoToMeeting). We prioritize professional development at all levels, offering opportunities to get involved in teams (like the Production team) or through workshops that help consultants translate writing center skills to other professions. Likewise, we hope writing centers remain responsive and flexible in how they imagine the work they do, and do not simply discard recent innovations to writing center practices when schools and students increasingly shift back to face-to-face operation. To do so would be to forget what we have learned about sustaining ourselves as communities of practice.

Notes

- The “Long Night Against Procrastination” events were initially designed by writing centers (now largely in partnerships with libraries) “to provide students with support on their writing assignments by offering extended hours and tutors to assist with proofreading, citation style, and developing thesis statements” (Kiscaden and Nash). Our “Kinda” Long Night is a condensed version, and Biology Long Night focuses specifically on supporting students with biology assignments.

Works Cited

Brooks-Gilles, Marilee, et al. “Writing Center Administrator Guidance in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Progression of a Position Statement.” The Peer Review, vol. 5, no. 1, 2021, https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-5-1/writing-center-administrator-guidance-in-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic-the-progression-of-a-position-statement/.

Draxler, Bridget. “Social Justice in the Writing Center.” The Peer Review, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017, https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/social-justice-in-the-writing-center/

Geller, Anne Ellen, et al. The Everyday Writing Center: A Community of Practice. Utah State UP, 2006.

Grutsch McKinney, Jackie. Peripheral Visions for Writing Centers. Utah State UP, 2013.

Kiscaden, Elizabeth, and Leann Nash. “Long Night Against Procrastination: A Collaborative Take on an International Event.” Praxis, vol. 12, no. 2, 2015, http://www.praxisuwc.com/kiscaden-nash-122.

Wenger, Etienne, et al. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge. Harvard Business Review, 2002.

Wenger-Trayner, Etienne, and Beverly Wenger-Trayner. “Introduction to Communities of Practice: A Brief Overview of the Concept and its Uses.” EB, 2015.

- The “Long Night Against Procrastination” events were initially designed by writing centers (now largely in partnerships with libraries) “to provide students with support on their writing assignments by offering extended hours and tutors to assist with proofreading, citation style, and developing thesis statements” (Kiscaden and Nash). Our “Kinda” Long Night is a condensed version, and Biology Long Night focuses specifically on supporting students with biology assignments. ↵