4 Gamifying Writing Center Design

Christopher LeCluyse

Westminster College[1]

As restrictions brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic descended on my campus in March 2020, I made the decision to switch our writing center to exclusively online operations. Campus remained open, however, and with it our writing center space. Those consultants who were comfortable doing so would continue working in the center to field any drop-by visitors still expecting in-person consultations, and the larger room would continue to be used for meetings, classes, and any students needing a place to work. I therefore had to determine how to rearrange the space to follow physical distancing guidelines. Since my assistant directors and I were physically distanced, working from our respective homes, we resorted to Roll20, a website typically used to play tabletop role-playing games (RPGs) remotely. (For more information about Roll20, watch the YouTube video below.) In tabletop RPGs, players portray characters in an imagined world, often using dice to determine the outcome of events and visual elements such as maps, illustrations, and miniatures to get a more accurate sense of locations, individuals, and other creatures in the game world. A virtual tabletop like Roll20 moves these game elements online and provides video, audio, and text chat for players to communicate with each other synchronously. We adopted Roll20 as a design tool because it is optimized for remote interaction involving shared visual elements—the tokens and battle maps of a typical RPG became furniture and a blueprint of the writing center in our case. In this article, I will synthesize writing center design and game studies scholarship to show how writing center design can be gamified through the use of an online gaming platform. While our use of this technology was born out of the necessity of the pandemic, it offers creative, and dare I say fun, possibilities for designing the post-pandemic writing center.

Fig. 1. A Video Introduction to Roll20 as an RPG.

This use of a gaming system to redesign our writing center encouraged both collaboration and agency. These are, of course, key writing enter values, but they are also essential components of most games. Gamifying writing center design exemplifies University of Utah games philosopher C. Thi Nguyen’s characterization of games as an art form that “engage[s] with human practicality—with our ability to decide and to do” (4). As he thoroughly examines in Games: Agency as Art, the medium of games is agency. Just as a painter may employ a repertoire of strokes or colors, a player in a game makes decisions and acts upon them. Besides the fact that our online design activity used a platform designed for tabletop RPGs like Dungeons & Dragons, our collaborative design session was a gamified experience that reflected Nguyen’s understanding of games. Using Roll20 provided agency for consultant administrators to make decisions about how to configure our space based on both practical and aesthetic considerations. In other words, we used one art form (gaming) to engage in another (design). Our “rules” were the constraints imposed on us by the pandemic: the need to keep people at least six feet apart.

Fig. 2. An audio interview with Chris LeCluyse about why he chose to integrate gaming applications in writing centers.

Before explaining how we redesigned our space through a gamified process, I will briefly consider notable treatments of design, gaming, and play in writing center contexts. (For an in-depth review of writing center practitioners’ discussion of space, see Singh-Cochoran and Emika.) Articles on the design of writing center spaces go back to at least 1950 with the publication in College Composition and Communication of the anonymous article “The Organization and Use of the Writing Laboratory: The Report of Workshop No. 9,” followed by another report the following year. Four decades later, writing center design resurfaced in the profiles of twelve writing centers described in Joyce A. Kinkead and Jeanette G. Harriss’s 1993 edited collection Writing Centers in Context. Descriptions of these spaces focus on flexibility and functionality in writing center design and on institutional factors (such as funding) that contribute to the success of the center. Typical of much work on writing center design, the profiles highlight features of the centers and their aesthetics (professional, academic, homey) rather than the process used to design them. A decade later, Leslie Hadfield, et al. wrote “An Ideal Writing Center: Re-Imagining Space and Design” in the edited collection The Center Will Hold. This article presents the results of collaboration between writing center practitioners and design students and faculty to envision the perfect writing center space at a hypothetical university, Alchemy U. While Hadfield et al. do not present their exercise as a game, its collaborative and imaginary nature does resemble the RPGs typically played on Roll20.

Soon after the publication of “An Ideal Writing Center,” Jackie Grutsch McKinney critically examined both the article’s assumptions and the typical figuring of writing center spaces as homey and comfortable. In her 2005 Writing Center Journal article “Leaving Home Sweet Home: Towards Critical Readings of Writing Center Spaces,” Grutsch McKinney critiques “An Ideal Writing Center” for being based on an imaginary exercise that did not involve consulting with real students, taking for granted that students would share the perspectives of consultants, administrators, and faculty. Turning more broadly to the descriptions in writing centers in Context, she notes that such descriptions “often mention round tables, art, plants, couches and coffee pots

In her 2005 Writing Center Journal article “Leaving Home Sweet Home: Towards Critical Readings of Writing Center Spaces,” Grutsch McKinney critiques “An Ideal Writing Center” for being based on an imaginary exercise that did not involve consulting with real students, taking for granted that students would share the perspectives of consultants, administrators, and faculty. Turning more broadly to the descriptions in writing centers in Context, she notes that such descriptions “often mention round tables, art, plants, couches and coffee pots ![]() with such frequency that these objects almost become iconic” and that in the collection “the closest thing to a common denominator connecting the diverse centers is the coffee pot—not philosophies of writing, not methods for tutor training, but the concrete presence of the coffee pot” (6). Against this focus on making the writing center home, Grutsch McKinney cites community literacy scholar Nedra Reynolds in calling for “a geographic emphasis” on writing center spaces, which “would insist on more attention to the connections between spaces and practices, more effort to link the material conditions to the activities of particular spaces” (qtd. in Grutsch McKinney 10). Nevertheless, some writing center scholars have articulated principled defenses of the “homey” writing center, such as Kaidan McNamee and Michelle Miley’s feminist advocacy of comfortable writing center spaces as sites for resistance.

with such frequency that these objects almost become iconic” and that in the collection “the closest thing to a common denominator connecting the diverse centers is the coffee pot—not philosophies of writing, not methods for tutor training, but the concrete presence of the coffee pot” (6). Against this focus on making the writing center home, Grutsch McKinney cites community literacy scholar Nedra Reynolds in calling for “a geographic emphasis” on writing center spaces, which “would insist on more attention to the connections between spaces and practices, more effort to link the material conditions to the activities of particular spaces” (qtd. in Grutsch McKinney 10). Nevertheless, some writing center scholars have articulated principled defenses of the “homey” writing center, such as Kaidan McNamee and Michelle Miley’s feminist advocacy of comfortable writing center spaces as sites for resistance.

One of the few articles that answers Grutsch McKinney’s call while focusing more on the process for designing rather than the features of a writing center space is William De Herder’s 2018 Praxis article “Composing the Center: History, Networks, Design, and Writing Center Work.” Adopting Reynold’s “geographic emphasis,” De Herder explains that writing center design requires negotiating multiple “competing factors: the spaces we inherit, the funds we are provided, the particular needs of the institution, the vision of the center’s administrative staff, and so on” (7). De Herder then synthesizes design scholars Thomas Rickert and Don Norman to describe the product of this negotiation. Effective design produces an “ambient rhetoric” of writing center space “intended to persuade both staff and writers toward a particular perspective or writing behavior” by providing particular “affordances of the landscape, features that shape how people interact with the space” (De Herder 12). While De Herder defines affordances in terms of the space’s structure and furnishings, the people using the space could also be considered affordances, particularly in our pandemic situation, which required distancing users of the space from each other. Through Norman, De Herder advocates for a design process that makes constructive use of constraints to limit both designers’ and users’ choices—an aspect of design theory that we will see aligns closely with game philosophy. Our own re-imagining of the writing center followed Grutsch McKinney’s and De Herder’s recommendations more out of necessity than design. First, our exercise was focused almost entirely on the material conditions of the writing center space—not on cultivating a sense of home but on meeting the pragmatic constraints imposed by the pandemic. While the literature on writing center design assumes that designing a writing center will be a voluntary, creative act, in our case the redesign of the space was brought on by the exigence of a public health emergency. Our constraints were not an aesthetic choice, nor were they imposed by institutional conditions per se. Rather, they responded to the need for physical distancing to minimize the spread of disease. This made the stakes of the “game” quite high.

While the design of writing center spaces is well-covered territory, the application of game studies to writing center work is just developing. After Daniel Lochman’s 1986 article “Play and Games: Implications for the Writing Center” and some treatment of play in Kevin Dvorak and Shanti Bruce’s 2008 book Creative Approaches to Writing Center Work, applying game studies to writing center praxis is only now emerging. Holly Ryan and Stephanie Vie’s 2022 edited collection Unlimited Players: The Intersections of Writing Center and Game Studies represents the first sustained synthesis of the two fields. After explaining how our administrative team used Roll20 to redesign our writing center space, I will add to this synthesis of writing center and game studies by applying Nguyen’s Games: Agency as Art to our design process. By doing so, I will show how gamifying writing center design through the use of this online technology maximized agency—a key aspect both of games and of writing center praxis.

The Pre- and Post-Game Writing Center

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the attendant switch to almost entirely online instruction in March 2020 contributed to a significant decrease in writing center traffic as well as requiring a redesign of our space. Prior to the pandemic in academic year 2018-2019, the Westminster College Writing Center recorded 1363 appointments, conducted by a staff of 14 consultants. In the 2019-2020 academic year, by contrast, we recorded 793 appointments—a decrease of nearly 42 percent. Our staff of ten consultants moved entirely online, though a few consultants worked in the writing center to arrange online consultations for students who dropped by. Before the redesign, the Westminster College Writing and Design Studio contained a much-used sofa we had acquired from the school’s collection of cast-off furniture, two tables and a desk used by the writing center proper, eight computer workstations arranged on tables to one side of the room, and multiple tables of various shapes and sizes (and their attendant chairs) filling the rest of the space (see fig. 4). Students would frequently use the space to do their own work—not necessarily connected to the writing center—and other offices and services would use the space for meetings. Figure 5 depicts a typical arrangement and use of the space on a busy day before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Like the RPGs typically played on Roll20, our response to the pandemic imposed a number of “rules,” or constraints in Norman’s terms, to guide the redesign process. These were largely derived from guidance from the Centers for Disease Control, alignment with choices being made by other campus services, space constraints, and college policies.

- Computer stations and chairs had to be at least 6 feet apart.

- Traffic patterns had to be open so that people did not have to pass close to each other.

- Surfaces had to be cleanable (i.e., no soft upholstery).

- Unused furniture had to be stored in the room.

Besides these constraints, the college reduced the occupancy of campus classrooms to enforce physical distancing, in turn requiring the use of additional spaces to accommodate classes still meeting in person. To provide extra instructional space, the Westminster College Writing and Design Studio would also be arranged to fit a small class.

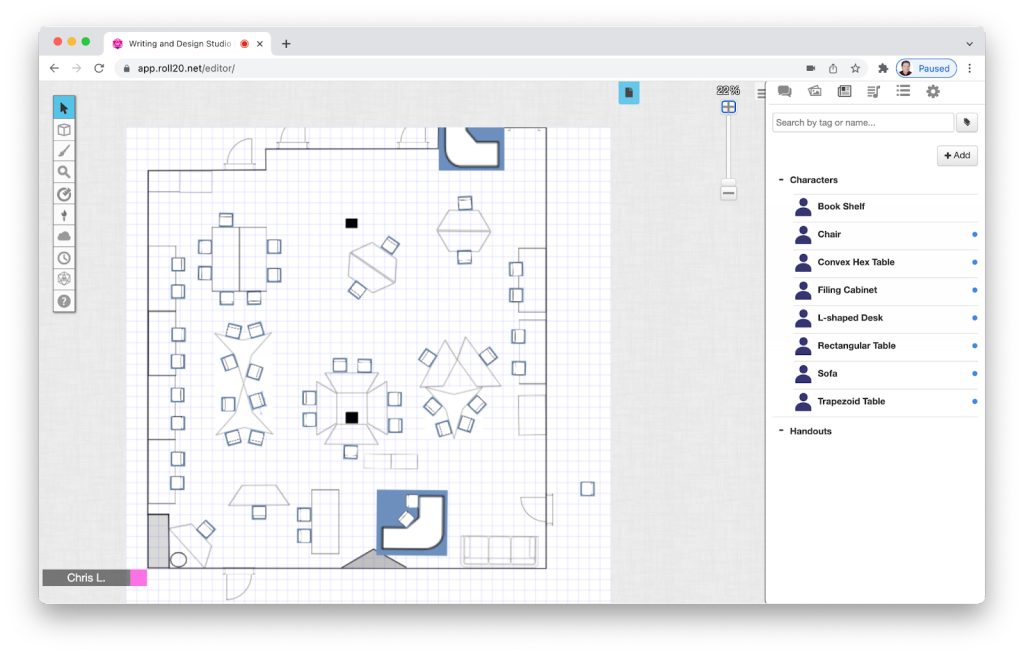

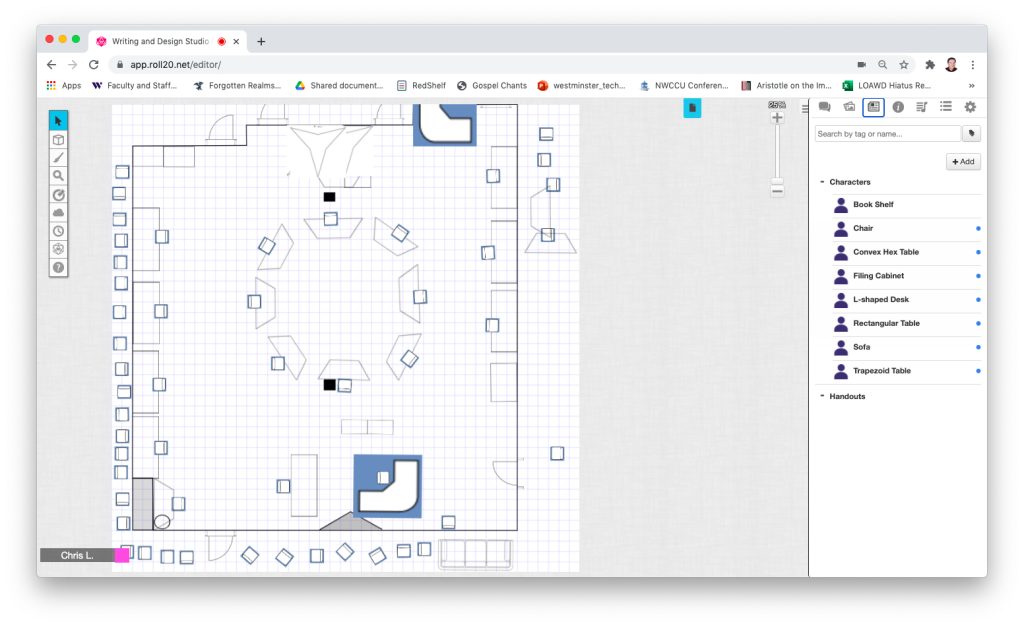

While these constraints provided some nonnegotiable limits on our design activity, using a virtual tabletop allowed us to collaborate while observing the need for physical distancing. The virtual tabletop easily leant itself to our design activity, enabling us to to control tokens representing the various pieces of furniture in the room against a map of the room itself. After measuring the room and the location of all the furniture in it, I drew a layout and reproduced it in Roll20, as represented in figure 5. I created tokens to represent each piece of furniture to scale and set the virtual tabletop so that anyone in the “game” could move them. I next invited my assistant directors—undergraduate peer consultants who mentor their colleagues and help shape writing center policies and practices—to join the game. We then met in Roll20 to discuss and plan the new layout, following the rules to generate a design within those constraints. During our meeting, we discussed various possibilities for arranging tables and chairs and moved tokens to indicate where we thought the furniture could go, as well as where to store unused furniture in the space. The result of our design activity is represented in figure 6. The thirty-one chairs dragged to the edge of the map were later stacked and stored either in an adjoining closet or in a cluster of furniture stacked at the edge of the room (visible at the top middle of the map).

Cultivating Agency in Gaming, Design, and Writing Center Praxis

Nguyen’s Games: Agency as Art helps us theorize this design activity as a prime example of what games are all about. In his in-depth exploration of the aesthetics of gaming, Nguyen demonstrates that games are indeed an art form, and that the aesthetic experience of gaming comes from making choices within the refined limits of the game. Just as artistic media make other art forms possible—the painter’s brush strokes, for example—Nguyen explains that the player’s choices are the medium of games: The game designer crafts for players a very particular form of struggle, and does so by crafting both a temporary practical agency for us to inhabit and a practical environment for us to struggle against. In other words, the medium of the game designer is agency (17).

Games create and shape experiences of play by empowering us to make choices within a set of constraints, or rules. In this respect, games strongly resemble the writing center design process as de Herder frames it: rules in games are like the affordances that create ambient rhetoric in a designed space. The “player” is the individual navigating the space, their agency shaped and limited by the affordances available in the physical space. In our case, those constraints were provided by the requirements of physical distancing. Our design activity, facilitated by the use of a virtual tabletop, involved playing with the choices we could make while observing those constraints. The fact that we played this game together using Roll20 facilitated Katrin Girgensohn’s articulation of peer tutoring as a form of collaborative leadership. Through the use of the virtual tabletop, we practiced among ourselves the kind of collaborative approach we advocate when working with writers.

Fig. 7. Nguyen explains his theoretical framework on the aesthetics of gaming

The use of Roll20 described here could be expanded to involve additional designers and could be gamified even further. While we used Roll20 as part of an internal design activity, outside architects, campus facilities staff, and writing center users could also be involved, provided that the “game” be explained to them ahead of time and they approach the activity as a way of informing their own design decisions. Collaborative writing center design could also be further gamified by applying additional constraints, crafting the medium of agency, in Nguyen’s terms. Going in turns, for example, or giving participants a limited number of moves in a turn would add an element of strategy as designer-players have to make decisions within a particular time frame. Doing so would also facilitate collaboration as players rotate, each having their turn. Additional constraints could involve having players control only certain pieces of furniture or a certain portion of the space, or in assigning each player a particular role. Here I take inspiration from territory-control games like Forbidden Island or Trogdor!! The Board Game, in which players must work together, each adopting a particular role or having a distinct talent or ability. In such cooperative games, either everyone wins or everyone loses. This cooperative ethos is yet another alignment between certain kinds of games and writing center praxis and was evident in our virtual tabletop design exercise.

This cooperative ethos is yet another alignment between certain kinds of games and writing center praxis

Although we used Roll20 to gamify writing center design, the platform could also be used for gamified training activities. Jamie Henthorn, for example, gamified her tutor-training course by having consultants-in-training choose various character classes typical of fantasy RPGs according to their interests: the summoner, involved in research to inform writing center training and handouts; the paladin, focused on promoting the center on campus; and the cleric, dedicated to promoting the wellness of the writing center staff (214). Trainees had to complete a set of common “quests,” or training activities, in addition to special quests determined by their class. In this case, the Roll20 tabletop could graphically represent the various quests, and trainees could move tokens representing their characters through the activities as a way of tracking their progress. Roll20 could also be used for single-session role-playing writing activities such as that designed by Alyssa Noch, in which writers adopt personas from video games, books, films, or history who work to “level up” their writing with the help of facilitators (teachers or writing consultants) who themselves adopt personas based on the kind of support they can provide. Writers can also receive items to assist with particular writing challenges, such as a sword “to symbolize the slashing, or cutting out, of unnecessary words, sentences, and paragraphs” (253). Although Noch presents her game as an in-person activity, it could easily be played on a virtual tabletop using tokens to represent the writers’ and facilitators’ characters as well as items, which can be further explained through the use of in-game handouts. A shared online document could serve as a workspace for writers and facilitators as in a synchronous online writing consultation.

Gamifying writing center design can thus be a way to negotiate the many constraints acting upon us and our spaces—physical, financial, and in our present moment, epidemiological—in an intentional and creative way. Digital technologies like the virtual tabletop can help practitioners exercise agency even in circumstances that seem to severely limit it. In the process, writing center design and praxis can become not only collaborative, but playful.

Works Cited

De Herder, William. “Composing the Center: History, Networks, Design, and Writing Center Work.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 15, no. 3, (2018), pp. 6-16, http://www.praxisuwc.com/153-de-herder.

Dvorak, Kevin, and Shanti Bruce, editors. Creative Approaches to Writing Center Work. Hampton, 2008.

Girgensohn, Katrin. “Collaborative Learning as a Leadership Tool: The Institutional Work of Writing Center Directors.” Journal of Academic Writing, vol. 8, no. 2, 2018, https://doi.org/10.18552/joaw.v8i2.472.

Grutsch McKinney, Jackie. “Leaving Home Sweet Home: Towards Critical Readings of Writing Center Spaces.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 25, no. 2, 2005, pp. 6–20, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442220.

Hadfield, Leslie, et al. “An Ideal Writing Center: Re-Imagining Space and Design.” The Center Will Hold, edited by Michael A. Pemberton and Joyce Kinkead, 2003, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46nxnq.13.

Henthorn, Jamie. “I Turned My Class into an RPG: A Pilot Study.” Unlimited Players: The Intersections of Writing Centers and Game Studies, edited by Holly Ryan and Stephanie Vie, Utah State UP, 2022, pp. 207–30.

Kinkead, Joyce A., and Jeanette G. Harriss, editors. Writing Centers in Context. NCTE, 1993, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED361707.

Lerner, Neil. The Idea of a Writing Laboratory. Southern Illinois UP, 2009.

Lochman, Daniel T. “Play and Games: Implications for the Writing Center.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 7, no. 1, 1986, pp. 11–19.

McNamee, Kaidan, and Michelle Miley. “Writing Center as Homeplace (A Site for Radical Resistance).” The Peer Review, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017, https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/writing-center-as-homeplace-a-site-for-radical-resistance/.

Nguyen, C. Thi. Games: Agency as Art. Oxford UP, 2019.

Noch, Alyssa. “Level Up.” Unlimited Players: The Intersections of Writing Centers and Game Studies, edited by Holly Ryan and Stephanie Vie, Utah State UP, 2022, pp. 252–57.

Norman, Don. The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition. Basic Books, 2013.

“The Organization and Use of the Writing Laboratory: The Report of Workshop No. 9A.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 1, 1950, pp. 31-32, https://doi.org/10.2307/355616.

“Organization and Use of a Writing Laboratory: The Report of Workshop No. 9.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 2, 1951, pp. 17-19, https://doi.org/10.2307/354618.

Rickert, Thomas, J. Ambient Rhetoric. U of Pittsburgh P, 2013.

Salt Lake Community College (SLCC) Student Writing & Reading Center. Photograph of the SLCC Student Writing Center. 24 Jan 2006.

Singh-Corcoran, Natalie, and Amin Emika. “Inhabiting the Writing Center: A Treatment of Physical Space: A Review in Five Texts.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 16, no. 3, 2012, https://kairos.technorhetoric.net/16.3/reviews/singh-corcoran_emika/physical-space.htmlkairos.technorhetoric.net/16.3/reviews/singh-corcoran_emika/physical-space.html.

Westminster College. Photograph of the Westminster College Writing Center. 2019.

- Westminster College changed its name to Westminster University on July 1, 2023. ↵