6 Finding Participatory Hospitality in Online Writing Studios

Abby Bernard, Niah Wilson, and Michelle Miley

Montana State University

In 2020, in our primarily face-to-face writing center, ideas of how we participate in an academic setting were upended. No longer was a visible body and an audible voice attached to “participant.” Suddenly, our writing center tutors, traditionally conducting face-to-face sessions with a few online sessions sprinkled here and there, were fully online, no longer knowing the “rules” for participation. Could one’s video be off and they still participate? How does one participate if constantly “muted”?

However, even before 2020, scholars were questioning the concept of participation. Michele Eodice, contributing to the ebook memorializing and honoring the work of Dr. Genevieve Critel, The Rhetoric of Participation: Interrogating Commonplaces In and Beyond the Classroom, notes how participation in academic settings has become commodified:

There is the sense from [Critel’s] data that writing teachers count “attendance” and “‘professional behavior” as participation while claiming community-building as a goal. . .This kind of participation is perfunctory, not genuine, because it is prescribed, and students know that; most also intuit they are not truly invited to interact and engage in the ways they are most able. (“Critel and Community”)

Drawing on writing centers’ foundations in peer-to-peer collaboration (Bruffee) and community (Geller, et. al.), Eodice develops the concept of “participatory hospitality,” which we have shortened to “PH,” as a framework to imagine participation between students and practitioners as truly collaborative and community building (“Critel and Community”).

PH is a guiding concept in our writing center, providing a foundation for our value-based practices (Hall). In tutor education, we imagine what “moves” embody participatory hospitality[1]. When we transitioned fully online, we needed new moves for inviting meaningful participation. One of our small group models, the online writing studio, offered us an environment to study. We began our study with the question, “How can writing center tutors foster PH in an online studio environment?” For this IRB-approved research project, we offer the framework behind PH. We then analyze transcripts available from our asynchronous studio conversations, and we offer tutor moves for practicing values based in PH.

Participatory Hospitality

Eodice merges “the qualities of academic hospitality and guided participation” to define the concept of participatory hospitality (“Participatory Hospitality”). She defines PH as resisting the valuing of individualism to one valuing interdependence. Through practices that treat students as worthy of “intellectual attention” (“Participatory Hospitality”), tutors and writers act as agents in a reciprocal relationship. PH acknowledges that as much as tutors offer students, students offer the tutors something as well. This mindset of reciprocity guides our tutoring practices.

Eodice notes that writing centers have often romanticized their idea of hospitality. Her critique echoes that of Jackie Grutsch McKinney (2005). Oftentimes, we imagine being “hospitable” means offering students passive comfort. These ideas of comfort stem from contemporary, commodified understandings of hospitality. But, Eodice writes, if we are practicing hospitality that enacts the “values found in our mission statements: access and equity” (“Hospitable Spaces,” par. 3.), we draw from ancient understandings of hospitality that understood hospitality as requiring meaningful action from both host and guest. Each has a set of “moves” that contributed to the relationship.

Eodice provides as an example of PH opening a one-to-one session by asking a writer, “What do I need to know today about you as a learner?” (“Participatory Hospitality,” para. 7). By asking this question, tutors practice PH, showing writers they have agency in directing the tutoring session and conversation. This same sort of participation can be achieved by similarly asking, “What can you teach me about writing?” As we interact with students, we think about how we can learn from each student.

Online Writing Studio

Our center has adapted Rhonda Grego and Nancy Thompson’s studio model for course partnerships. Studios are hosted in the writing center, a “third space” outside the classroom, what we call “first” space where the class is all together and teacher/student power dynamics are present, and the writer’s second space, where the individual student composes on their own. In our version of the studio, five to seven students meet regularly in a group. Their discussion and work together is facilitated by a writing center tutor (Miley). The faculty member is not “in” the studio space at any time. The third space differentiates the studio model from a writing fellows model where a fellow is embedded into a class setting (Mackewicz and Kramer Thompson, p. 168).

Unlike in a one-to-one session, where the role of tutor necessitates facilitating participation with one writer, a studio includes many people; this changes the moves tutors who are facilitating the studios can make to practice PH. Because tutors are not embedded into the class, we rely on the participants for course-specific content knowledge. Our interactions highlight the collaborative nature of writing as students receive feedback from their audience and respond to it. … the studio disrupts the typical teacher/student dynamic, creating a participatory environment for group members.Separate from the classroom and guided by what the students bring to the space, in its ideal form the studio disrupts the typical teacher/student dynamic, creating a participatory environment for group members.

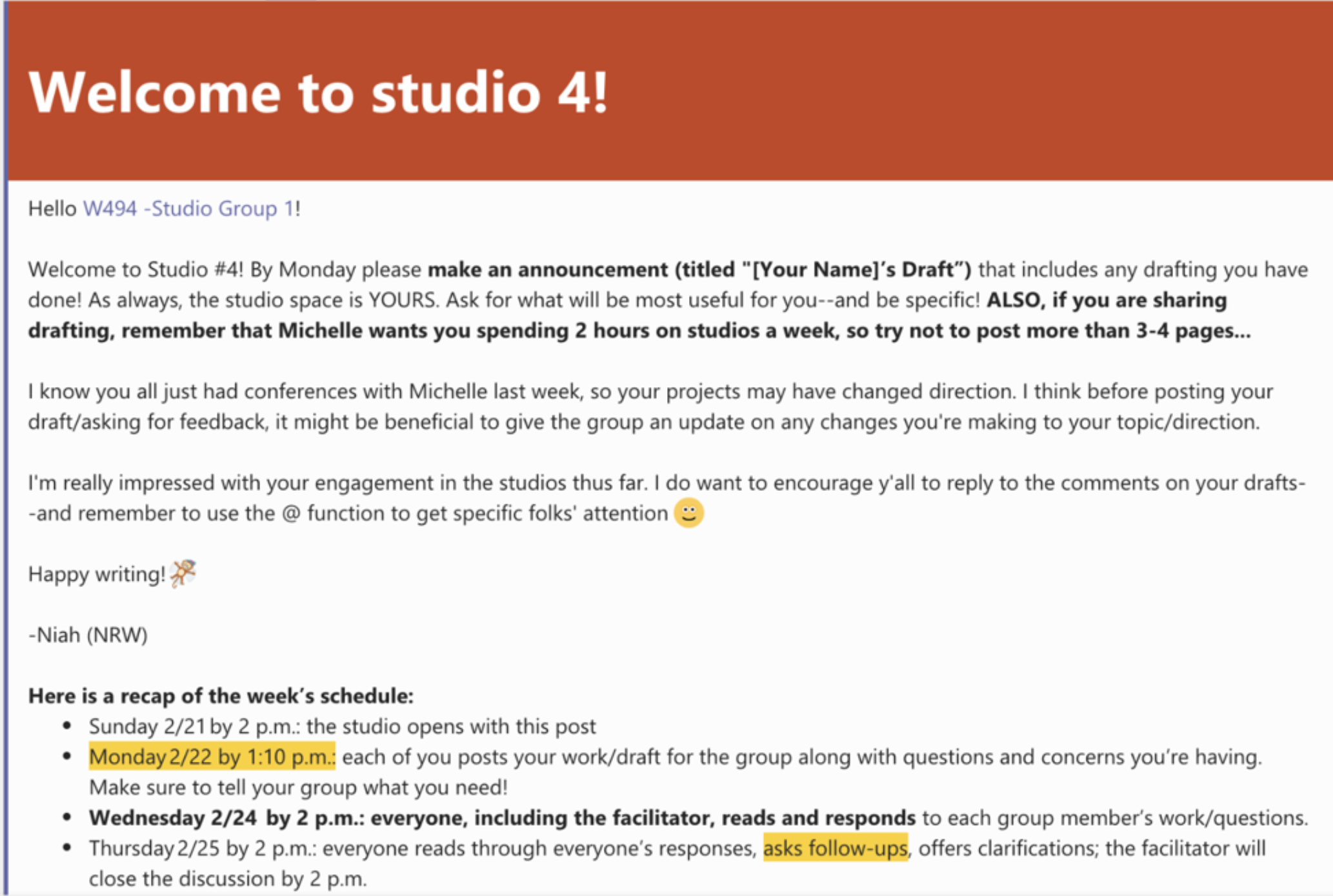

When we moved into the online environment in March of 2020, we wanted to preserve the level of collaboration we had fostered in in-person studios. Drawing from Michelle’s experience with online studios (Miley), we created discussion boards in Microsoft Teams with an asynchronous cycle for students to post and respond to one another’s writing. The typical online studio schedule follows a four-day cycle as shown in figure 1.

For example, on day one the studio will open with a “host post” from the facilitator, a writing center tutor. On day two, each participant will post their draft along with questions. By the evening of day three, everyone–the tutor acting as the studio facilitator[2] along with all the group members–is responsible for reading and responding to each group member’s work. Finally, on day four, all group members and the facilitator will read through everyone’s responses, offer follow-up questions, and continue the conversation. The facilitator will close the discussion. Studio groups will go through this cycle an average of five times per semester, often every other week.

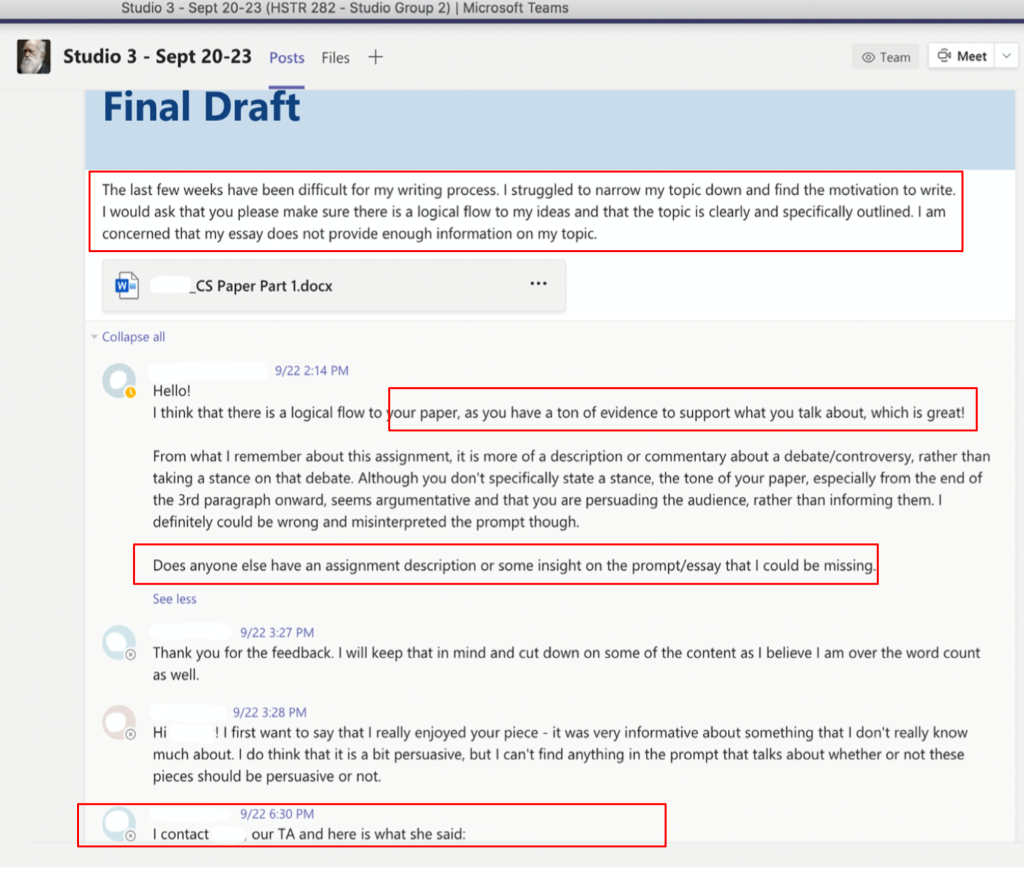

In 2020, as we transitioned our studios into Teams, we worked to make the space hospitable. This hospitality begins with the facilitator’s opening post. The host post welcomes participants, provides schedule reminders, and reminds participants that the studio space is directed by them. For example, in figure 2, Niah started one host post with “Welcome to Studio #4! By Monday please make an announcement that includes any drafting you have done. As always, the studio space is YOURS. Ask for what will be most useful for you—and be specific!” By asking writers to ask for the specific feedback they want to receive, we let them guide the conversation and set the curriculum.

Initially, asynchronous studios, which extended the conversation from one face-to-face hour across several days online, seemed to make participation more difficult. Without an immediate response to a post, how would we know if someone was participating? However, we soon noticed some benefits. As Kristi and Shawn Apostel note, “Opportunities posed by various types of online feedback introduce possibilities for collaboration as well as embracing new technologies in both writing studios and classroom settings” (p. 101). Because past studio conversations for studio participants are archived, the online studio model allows for accessibility. Transcripts allow those who need time to process a record of the conversation. Moreover, our studios foster flexibility. Participants can engage in discussion according to their schedules. This flexibility mitigates scheduling challenges from in-person studios. Because the pandemic has created more complexities for students to navigate, we have embraced this opportunity for increased flexibility and accessibility. We do note that, while responding to one another’s writing does not seem to take up any more time than the hour of a face-to-face studio for the class participants with drafts typically 1-3 pages long, the writing center facilitator did notice it took longer to respond and facilitate the conversation than in a face-to-face studio. In a face-to-face studio, because the studio facilitator makes sure all students and student texts receive attention, they may ask the studio members to specify a passage for the group to focus on rather than worrying about everyone reading whole drafts. We found that because of the asynchronous nature of the online studio, the studio facilitator did not have to worry about all texts receiving attention within a single hour. They found themselves spending more time reading through each paper and responding more deeply than time allows in a face-to-face setting. In order to maintain a reasonable time for the studios, as a general rule, we schedule an hour and a half for each online studio session for the facilitator.

But we wanted to know how we could foster PH online. How do we create what Destiny Brugman described as a “brave and safe space,” one where writers feel comfortable sharing their writing while also being comfortable giving and receiving feedback? And how do we do this when many of our studio members, because of blended course structures, might not actually know each other in person? How do we foster a space online where writers can give honest feedback to one another and where all group members learn from one another, including us?

Learning from Our Conversations

The transcripts from our online studio conversations made visible when and how we foster PH through our language. For this study, we chose two classes of about thirty to forty students each, but soon realized that, because of time constraints, we needed to choose specific studio groups as case studies. We focused our analysis on two studio groups that appeared to us to have high levels of participation. We also analyzed two groups with lower levels of participation to compare environments. Each studio group completed an average of five cycles of online studios over the course of the semester and had on average five students and one facilitator participating. As we read through the transcripts of online studios for examples of PH, Abby and Niah looked for transactions that suggested authentic participation among the students, coding for three specific themes from Eodice’s definition of PH:

Interdependence and Collaboration

Eodice argues PH allows us to push back on the “insistent individualism” American universities promote, fostering an environment of interdependence and collaboration. Studios resist this individualism and promote interdependence by making each student a writer and a reader, responsible both for sharing their own writing and offering feedback to others. We looked for moments of writers offering the group their knowledge.

For example, in figure 3 a participant replied to a post: “From what I remember about this assignment, it is more of a description or commentary about a debate/controversy, rather than taking a stance […] Does anyone else have an assignment description or some insight on the prompt/essay that I could be missing?” In response, a second participant brought in additional resources, sharing information gleaned from the course TA. The writers collaborated by pulling their assignment sheet and class resources into this space, participating with one another. Additionally, participants demonstrated interdependence and collaboration as they responded to a writer’s question about whether this assignment should be persuasive or not. The openness of studio members asking for guidance and deferring to other resources, and then sharing those resources, fosters a participatory space as writers help one another.

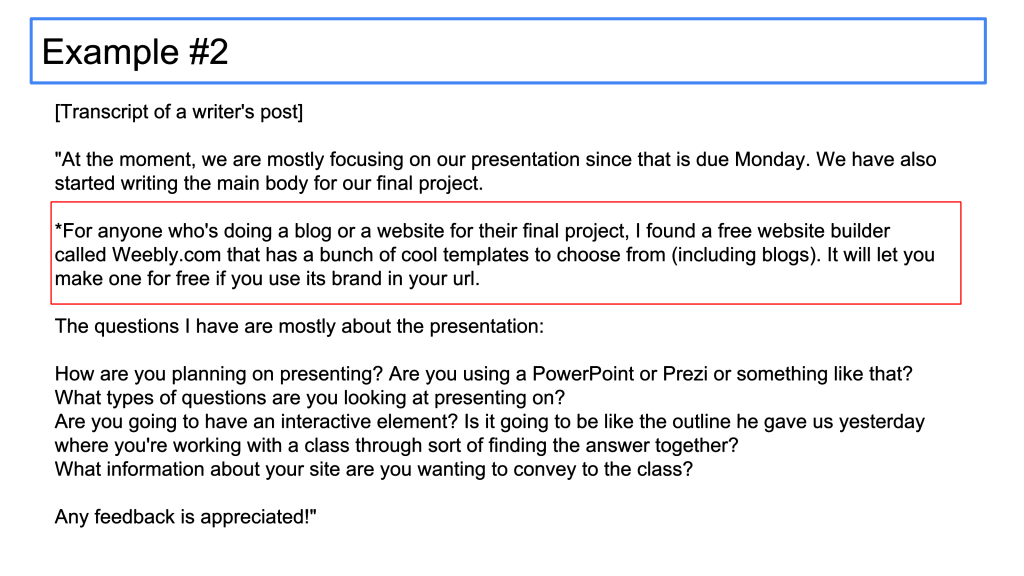

Figure 4 offers another example of studio members sharing resources with one another. In the host post, the facilitator invited participants to tell the group where they were in their writing process. However, one writer instead solicited feedback and input on their presentation (a part of their assignment, but not what we may typically expect from a studio draft). The participant set the curriculum: “At the moment, we are mostly focusing on our presentation since that is due Monday […] For anyone who’s doing a blog or a website for their final project, I found a free website builder called Weebly.com.” Participants exercise PH by directing the feedback. Additionally, writers are resisting insistent individualism by sharing resources they found. The writer is giving the gift of their knowledge while also asking for feedback, thus engaging in the reciprocal nature of PH in studios.

Community Formation

For PH communities to form, not just the facilitator but everyone in the studio must make the space hospitable. In our analysis, we looked for conversations which built community, specifically moments where writers leaned on each other—and on the studio space—as a way to find connection.

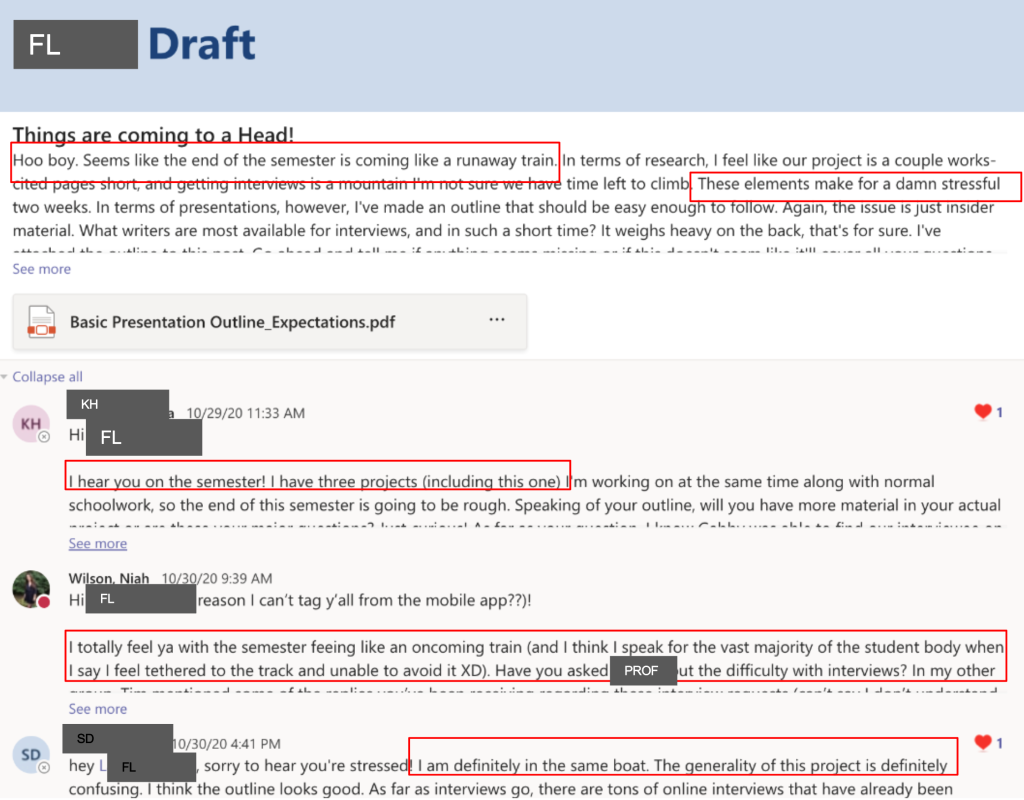

In one such transcript, the initial writer, the facilitator, and the other studio members all commiserated with each other about the difficulty of the semester. The original participant’s post starts, “Seems like the end of the semester is coming like a runaway train. In terms of research…” to which a second participant responds, “I hear you on the semester! I have three projects (including this one)…”. To both of these, a third participant chimed in: “… I am definitely in the same boat. The generality of this project…”

After each commiseration, the conversations dive into project specifics. They are establishing community and finding support in the studio setting by using commiseration to make the space more welcome, then getting into the writing. This creation of community is significant when we consider the feelings of isolation that can accompany online learning. As figure 5 illustrates, the online studio space created an environment where writers felt comfortable giving and receiving feedback and establishing personal connections.

Shared Learning

Third, we looked for instances of shared learning. By recognizing participants as the experts on their subjects, writers can be more honest with their feedback and recognize the value and opportunity to learn from one another. In our analysis, we found examples of different tutoring moves that promote this embodiment of PH. We looked for moments when facilitators or participants asked one another for further information about a topic, particularly when it leaned into expertise beyond the assignment parameters.

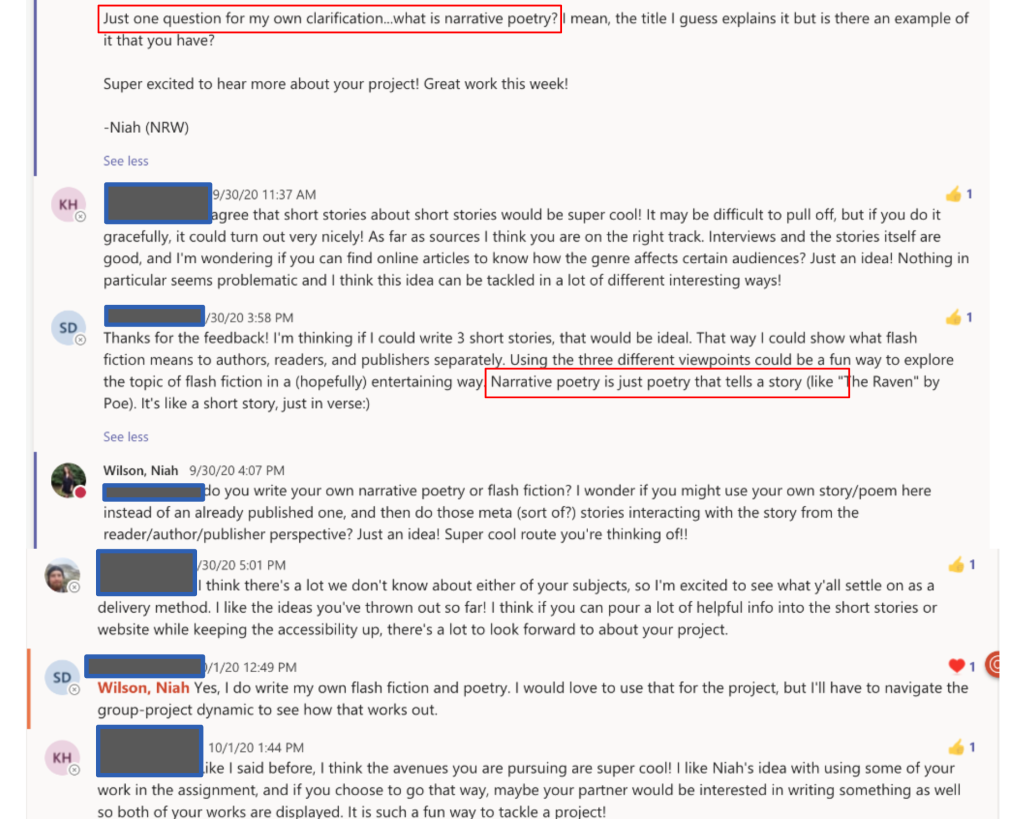

In the example shown in figure 6, the facilitator asked for clarification about a writing genre: “Just one question for my own clarification…what is narrative poetry?” This clarification further opened the discussion and allowed each group member to learn from one another: “Narrative poetry is just poetry that tells a story (like ‘The Raven’ by Poe).” As the writers recognized they were the experts on their subjects, they were more open to sharing information about their own writing, including helping the facilitator learn.

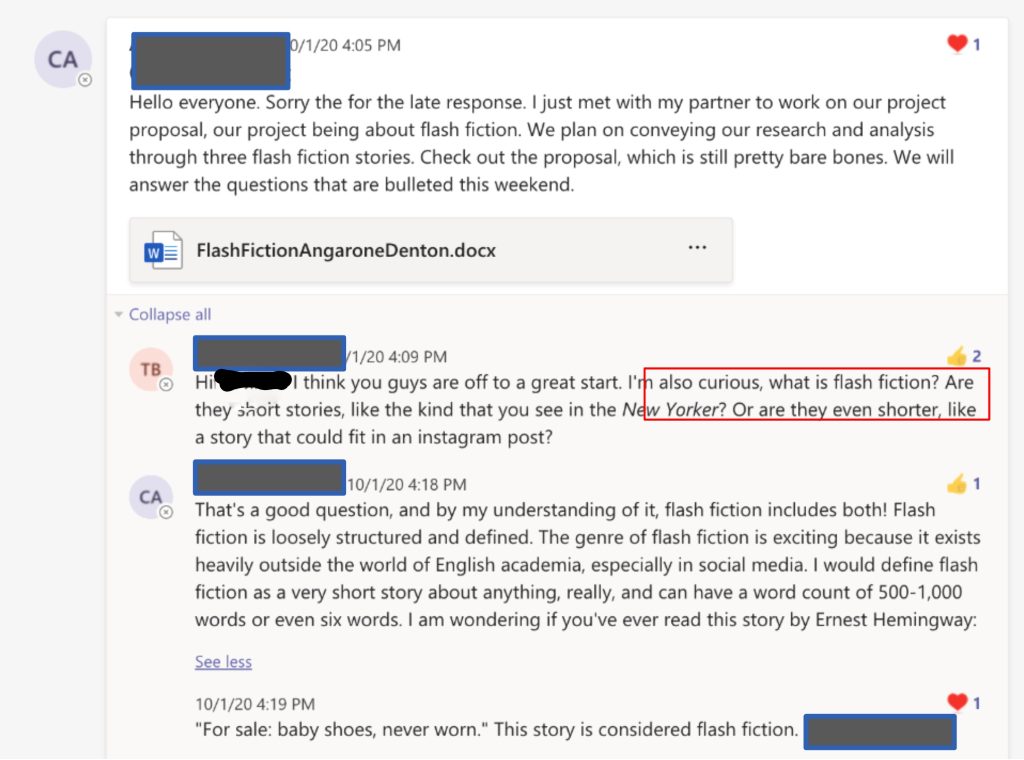

In figure 7, a participant responded to a post with, “I’m also curious, what is flash fiction?” The original writer replied, “That’s a good question […] I would define flash fiction as a very short story about anything…”. Note that, because the studio is made up of peers from the class as well as the writing center facilitator, students are sharing knowledge with one another. The facilitator may not have known the definition of flash fiction, but someone in the group did. All of us are learning from one another, embodying the PH value of reciprocity. Reciprocity often occurs in a one-on-one tutoring session when a peer tutor learns from a writer; here that learning extends to include multiple experiences and knowledges from which the group members can learn.

When PH Did Not Exist in Our Online Studios

As we looked for moments of PH, we also looked for moments when facilitators might shut down or hinder the participation of studio members. Hannah Telling (2020), a former tutor, used gesture drawings to study the physical moves between writer and tutor that embody the values of PH. In her study, she noted moves that actually shut down PH. For example, when a tutor eagerly leans towards a writer, they may leave no space for the writer to participate (32). In conducting our transcript analysis, we, too, found examples where a facilitator’s moves shut down PH.

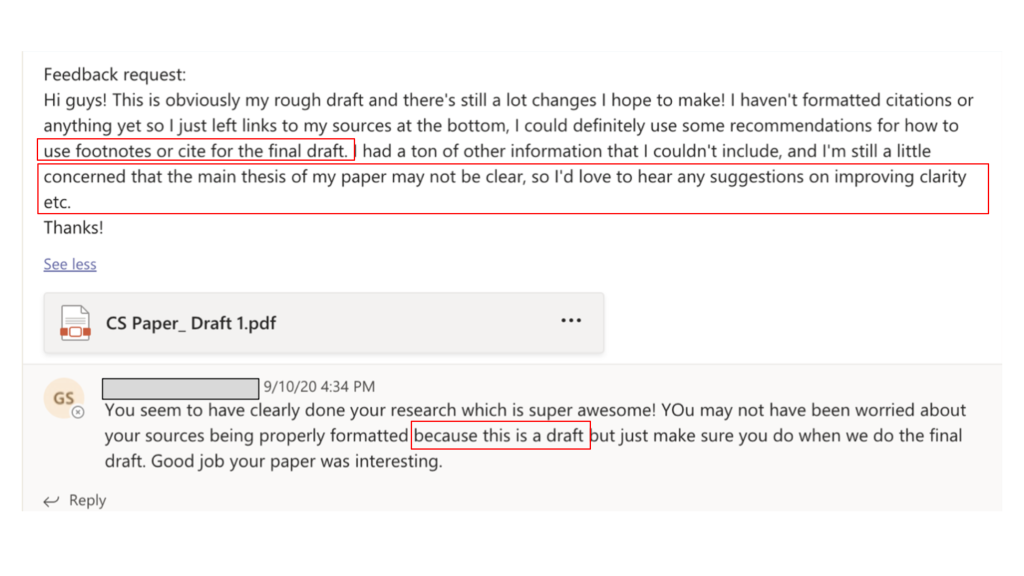

In one example shown in figure 8, the first participant asked for specific feedback on citations and improving clarity of their thesis. The participant who responded did not give the feedback requested, instead telling them not to worry about it because this is “just a draft.” Rather than redirecting to a more reciprocal conversation, the facilitator did not join in. While everyone in the studio needs to contribute to making PH happen, we recognize the facilitator has the responsibility of inviting PH through modeling participation.

In other transcripts, we identified instances of an over-eager facilitator. When a participant asked several questions, the facilitator jumped in to answer all of them. No other participant replied, likely because the facilitator covered all of the feedback. Rather than answering all the participant’s questions, the facilitator could have deferred to the other studio members. This reminds us of the tutor who leaned into the space without giving the writer room to participate (Telling 32). Giving the writer(s) some room, physical or virtual, to participate fosters PH.

Facilitator Moves to Encourage PH

From our analysis, we identified certain moves facilitators made that both encouraged participation and modeled PH for the studio members in the online studios. We’ve listed some of those moves below, noting that these are moves that may be adapted to other online group spaces. We provide these suggestions for centers wishing to create PH in online writing spaces:

TAGGING

Invite all to participate by tagging. In an in-person setting, facilitators can invite someone to join the conversation by saying their name. In an online setting, tagging—in Teams, for example, using the “@” symbol with a name so the individual receives a notification—works in much the same way. When someone is “tagged,” they are reminded that their participation is desired, and that they are an active participant in the conversation. Figure 7 depicts “tagging” in Microsoft Teams.

ASKING QUESTIONS

Ask questions to solicit participants’ contributions of knowledge and authority. In an online environment where a quick internet search can answer many questions, it is helpful to instead ask questions of the other participants to recognize and draw from their knowledge and authority. This move also reminds participants that the facilitator, though “host,” is not simply there to offer all the answers. Rather, the facilitator is participating and learning too. Helping the students find the answers rather than simply handing them over is important to PH.

NOT ADDRESSING EVERY QUESTION

Resist the temptation to address all participants’ questions. Sometimes, an important tutor move is not to do something. By this, we mean resisting the urge to jump in and address all of the feedback for the entire piece as this closes off the conversation to other studio participants. This move reflects the same findings Telling observed in her in-person analysis when she noted how our over-eager “leaning in” left no space for the writer to participate.

Conclusion

In Fall 2021, we shifted back to both in-person and online studios. Though our campus moved back to in-person fairly quickly, we recognize the need to continue offering flexible and accessible models for students. We have continued to use our online studio model, and we plan on maintaining this model in the future as we recognize the benefits of flexibility and accessibility.

Through our analysis, we observed significant moments of creativity from our tutor facilitators. Moreover, by seeing the moves we make in online conversations and considering their analogous techniques in in-person studios, tutors can become more cognizant of when they are not practicing participatory hospitality. As we continue to analyze our online studio spaces, we expand the toolbox of approaches we can take to ground our value-based practices in participatory hospitality. We also know that our toolbox expands as we learn from others in the writing center community. We hope that our work invites others to imagine how PH exists within their writing center models, adapting our approaches to their own online and face-to-face environments and sharing with us the moves they make to invite writers into a PH relationship.

Works Cited

Apostel, Shawn, and Kristi Apostel. “The Flexible Center: Embracing Technology, Open Spaces, and Online Pedagogy.” Writing Studio Pedagogy: Space, Place, and Rhetoric in Collaborative Environments, edited by Matthew Kim and Russell Carpenter, Rowman & Littlefield, 2017, pp. 93-111.

Banaji, Paige V., et al., editors. The Rhetoric of Participation: Interrogating Commonplaces In and Beyond the Classroom. Utah State UP, 2019, https://ccdigitalpress.org/book/rhetoric-of-participation.

Bruffee, Kenneth. “Peer Tutoring and the Conversation of Mankind.” Writing Centers: Theory and Administration, edited by Gary A. Olsen, NCTE, 1984, pp. 3-15.

Brugman, Destiny. “Brave and Safe Spaces as Welcoming in Online Tutoring.” The Peer Review, vol. 3, 2019, https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/brave-and-safe-spaces-as-welcoming-in-online-tutoring/. Accessed 29 April 2022.

Eodice, Michelle. “Participatory Hospitality and Writing Centers.” The Rhetoric of Participation: Interrogating Commonplaces In and Beyond the Classroom, edited by Paige Banaji, et al., E-book, 2019, https://ccdigitalpress.org/rhetoric-of-participation. Accessed 29 April 2022.

Geller, Anne Ellen, et al. The Everyday Writing Center: A Community of Practice. Utah State UP, 2007.

Grego, Rhonda, and Nancy Thompson. Teaching/Writing in Third Spaces: The Studio Approach. Southern Illinois UP, 2008.

Grutsch McKinney, Jackie. “Leaving Home Sweet Home: Towards Critical Readings of Writing Center Spaces.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 25, no. 2, 2005, pp. 6-20, doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1526.

Hall, R. Mark. Around the Texts of Writing Centers: An Inquiry-Based Approach to Tutor Education. Utah State UP, 2017.

Mackiewicz, Jo, and Isabelle Kramer Thompson. Talk About Writing: The Tutoring Strategies of Experienced Writing Center Tutors. Taylor & Francis, 2015.

Miley, Michelle. “Writing Studios as Countermonument: Reflexive Moments from Online Writing Centers in Writing Center Partnerships.” The Writing Studio Sampler: Stories About Change, edited by Sally Chandler and Mark Sutton, The WAC Clearinghouse, 2018, pp. 167-183, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/studio/chapter10.pdf. Accessed 29 April 2022.

Telling, Hannah. “Drawing Power: Analyzing Writing Center as Homeplace through Gesture Drawings.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 38, no. 1-2, 2020, pp. 19-43, doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1919.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank our fellow peer tutors and their studio groups. Without their willingness to share studio conversations, our project would not have been possible. We thank Landon Shipley and Eddie Bakko for their feedback early in our writing process, and we thank the WLN readers and editors whose feedback bettered our work. Finally, a big thanks to Markita Williams, fellow peer tutor and studio facilitator, for her willingness to offer her expertise with graphics.

- Though writing studios do differ from writing fellows, our work may add to Jo Mackiewicz and Isabelle Kramer Thompson’s call for “more talk between writing fellows and student writers” (p. 169). We note our work looks at the moves we make to practice participatory hospitality, a concept that guides us to make value-based practices (Hall). ↵

- To emphasize that the role of a tutor in a writing studio requires facilitation of a group, we name that person the “facilitator” rather than “tutor.” The tutors facilitate the studios. ↵