7 “A Triumph Over Structures That Disempower”: Principles for Community Wellness in the Writing Center by Yanar Hashlamon

Keywords: Disability studies, Black feminist studies, social justice, community wellness, community care, professional development

Introduction

In her analysis of Black feminist texts, Tamika Carey writes that for exploited populations, “Achieving wellness is a triumph over the structures that disempower” (62). Amidst writing center studies’ turn to wellness, I find myself thinking more and more on this quote, and considering what about writing center work makes wellness a necessity, and for whom. Independent of this trend is another: the stories written by women of color in the writing center published since 2018—those by Neisha-Anne Green, Talisha M. Haltiwanger Morrison and Talia O. Nanton. Experiences of racism local to institutions and in our broader scholarly community don’t yet intersect with our budding wellness scholarship. However, the stories Green, Haltiwanger Morrison and Nanton tell are painfully familiar to many marginalized writing center professionals. Our wellness scholarship must contend with the oppressions stratifying writing center studies, as asking how to support writing center workers is undeniably a question of institutional and intersectional oppressions.

Seeing wellness become a subject of focus in writing center studies raises the question: if it could be subversive for writing center professionals to care for themselves and for each other, what forces and institutional structures are subverted by writing center wellness? Put another way, what oppressions necessitate wellness and how can we name, resist, and otherwise triumph over them? Such a line of questioning turns our attention to the activist roots of self-care and their applicability to writing center work. In an activist context, self-care was made necessary by institutional racism that pathologized Black bodies and foreclosed officialized channels of care (Harris).

Where I see calls for writing centers to align with university counseling services (Degner et al.; Perry), I think about how, for many minority workers, university services are often inaccessible. Today, 72.4% of university counselors in the US are white (LeViness et al. 53). Students of color are less likely to seek support than their white peers in higher education (Hyun et al.) despite experiencing higher levels of stress (Dyrbye et al.) and greater barriers to academic success (Maton et al.)—points that also hold true for first-generation students in comparison with non-first-gen students (Stebleton et al.). Online counseling resources and outreach often are not inclusive to queer people (McKinley et al.; Kennedy and Baker) and the overwhelming majority of university counselors themselves, 96.2%, identify as cis-male or female, 83.9% as straight, and 89.4% as non-disabled (LeViness et al. 53). While student counseling services protect confidential disclosure of abuse, other resources, such as student advocacy offices, often do not.

With institutional disparities in mind, this essay acts as a position statement to orient and complicate writing center wellness at the nascent stage of its scholarly discussion. I argue that achieving wellness is the triumph over that which makes workers unwell in writing centers’ professional and scholarly spaces. Put short, wellness is made necessary by our community and must be addressed with community-based systems of support.

I will briefly delineate the professional and activist histories of wellness and self-care to suggest how both apply to the writing center. The political dimensions of these histories inform a discussion of two recent works by Black writing center scholars: Green’s “Moving beyond Alright: And the Emotional Toll of This, My Life Matters Too, in the Writing Center Work” and Haltiwanger Morrison and Nanton’s “Dear Writing Centers: Black Women Speaking Silence into Language and Action.” I then posit four principles for community wellness in the writing center to help commit our scholarship and professional development to justice-oriented practices.

Parallel traditions of wellness: individual resilience and community action

Self-care locates its professional roots in the mid-20th century, originating in the caring or helping professions: the work of therapists, doctors and nurses, social workers, and educators (Skovholt and Trotter-Mathison). For these workers, wellness is based on strategies to prevent burnout and otherwise address stresses contingent to interpersonal labor (Stamm). Supporting clients through traumatic events and supporting oneself through compassion fatigue and secondary stress are all deeply applicable to tutoring. In wellness scholarship published thus far in our discipline, writing centers seem well poised to apply this professional definition of self-care, especially in regards to mindfulness and mental health (Mack and Hupp; Degner et al.; Perry; Featherstone et al.). The recent 2020 WLN special issue on Wellness and the Writing Center and this digital edited collection both add empirical and pragmatic wellness knowledge to our field’s oldest corpus of scholarship. Yet, how much of this work is equipped with the historical context and political scope needed for self-care’s activist application—the application that emphasizes the wellness of minority and disabled workers in writing center practice? As important as it is that we establish community around peer experiences, we cannot flatten out the differences marginalized workers experience that affect and add stress on to those same experiences. The activist history of self-care and its connections to Black history and community wellness all contextualize the ways that the stories of women of color in the writing center directly bear upon wellness.

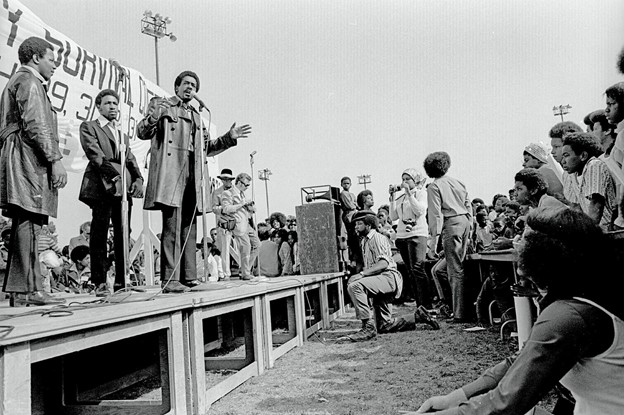

Contrary to the “self” in self-care, activist organizing around self-care is a story of community organizing in the American civil rights movement. The struggles against socioeconomic marginalization and racism in the United States tied healthcare to broader forms of material stratification: that is, disparities in access to wealth, housing, and education. As Aisha Harris writes, “poverty was correlated with poor health,” and community organizers worked “to dismantle hierarchies based upon race, gender, class, and sexual orientation,” as identity was deeply tied to disparate access to health care. Most notably, the Black Panther Party formed community clinics throughout the 1970s in resistance to institutionalized discrimination and inaccessible medical care in Black communities (Nelson 106). The Party added a call for “completely free health care for all black and oppressed people” to their 1972 party platform, the “Ten Point Program” (Bassett). As a part of their platform, the party marked community health initiatives, like the Black Community Survival Conference depicted below, as a core priority supported by founding members like Bobby Seale.

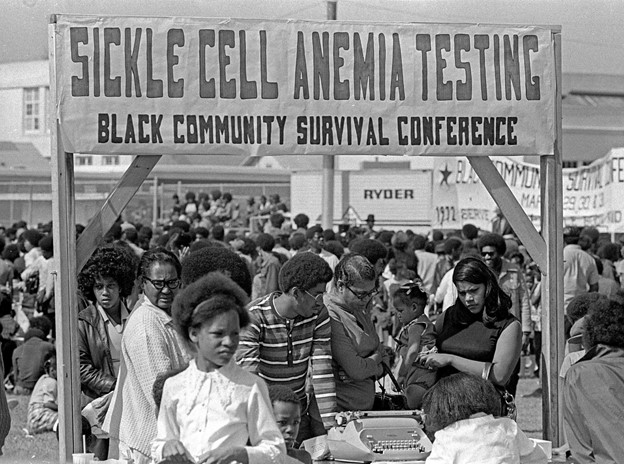

Community wellness is key to understanding the activist work of the Black power movement (Figure 1). Operating from the precept that social and material disparities disempower vulnerable groups, community wellness directly addressed health needs through community empowerment and support in the 1970s (Jenkins 388). Engaging in collective struggle is a key element of health justice—a process exemplified in the Black Panther Party’s networks of care, enacted through People’s Free Health Clinics that operated across the United States. Medicine has historically pathologized Black bodies, marking them as deficient and subject to surveillance and control (Erevelles 146). Contextualized by this history, the Panthers’ health activism extended to group advocacy, empowering Black and impoverished people with the support required to interact with doctors and demand healthcare (Nelson 109). Figure 2 depicts one of the Black Panther Party’s community health conferences, which included free medical testing and information about disparities in healthcare in Black communities.

Beyond medicine, self-care in activist circles is perhaps most famously tied to Audre Lorde’s 1988 book, A Burst of Light—specifically her epilogue, where she writes, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare” (130). Beyond the importance of group advocacy, Lorde speaks to the ways that everyday survival and prosperity disrupt norms of oppression, turning our attention back toward workplaces. The interpersonal strains caused by caring professions are not always conditions of the job and extend instead from social and material conditions that marginalize communities more broadly.

The interpersonal strains caused by caring professions are not always conditions of the job and extend instead from social and material conditions that marginalize communities more broadly.

Professional and political wellness in the writing center

Historically, self-care in activist contexts has been as much about personal wellness as it has been about building community support, accountability, and alternatives to discriminatory institutions. Conversely, the professional dimension of self-care and wellness literature often emphasizes “resilience,” as in the title of Skovholt and Trotter-Mathison’s history of and guide to self-care, The Resilient Practitioner. This emphasis on resilience holds significant effects for marginalized people who live and work within oppressive material and social conditions. By locating responsibility in the individual, resilience can flatten out the structural inequities that necessitate self-care in the first place.

On the oppressive ramifications of self-care, Thomas Lemke writes that neoliberal ideology shifts “the responsibility for social risks such as illness, unemployment, poverty, etc., and for life in society into the domain for which the individual is responsible and transform[s] it into a problem of ‘self-care’” (201). As part of a service-oriented profession, writing center scholarship often perpetuates an ethic of individual responsibility when it comes to caring for oneself and for clients. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors is one example of our field’s habit to simplify the workplace relations of writing centers and thus simplify the tensions of our professional work. In its most recent edition, tutors are told to “be patient and polite” in sessions with sexist and racist writers, but to not “take the writer’s viewpoints or language personally” (Ryan and Zimmerelli 106). Racism and sexism are treated as aesthetic choices—as words that are spoken, rather than histories that are lived and traumas that are suffered.

Racism and sexism are treated as aesthetic choices—as words that are spoken, rather than histories that are lived and traumas that are suffered.

Where The Bedford Guide breaks from individual decision-making in harmful sessions, it gestures to workplace community by suggesting that as a tutor, “you should feel free to remove yourself from the tutoring session … if possible, work with the director to arrange for another tutor” to take over (106). There is no account of the realities that marginalized students live, or how terminating a session might be irreconcilable with the pressure to be resilient. Black workers regularly have their job performance “scrutinized more closely than the performance of white workers” across a multitude of industries—a trend tied to hiring discrimination and shorter employment duration (Cavounidis and Lang 1). Writing centers are no exception from the kinds of workplace discrimination Cavounidis and Lang describe, as evidenced by Talia Nanton’s story. In her essay with Haliwanger Morrison, Nanton describes how her language was policed in her writing center, how she was “accused of not taking criticism well” and blamed for the actions of her coworkers. The other reality embodied in her story is a painfully familiar one for marginalized workers—that the quality of our work will not spare us from discrimination.

Despite Nanton taking on “the earliest shift three days a week,” her being “the first to prop the door open in the morning,” never being late, and being “careful not to complain,” she was still reprimanded for something as minor as “not saying ‘hello’ to another co-worker, however unintentionally.” That “the guise of making sure the center remained ‘a safe space’” was used to discriminate against Nanton shows what happens when writing centers’ notions of professionalism protect white fragility. Workplaces are steeped in politics of respectability in the way that marginalized workers are expected to act a certain way to solve problems that systemically inform how they are treated and oppressed. Explicitly, this ethic of personal responsibility is clear in cases of discrimination in the writing center, but it pervades more subtly in instances where marginalized workers are asked or expected to educate others about their identities. Wellness must be oriented to the experiences of the oppressed—a need best exemplified by the stories of workers told in our scholarship, which might appear unique in writing centers, but are instances of a much bigger pattern of workplace marginalization and abuse.

We do not have to imagine the harm that an ideology of personal responsibility for wellness has inflicted on marginalized workers in writing centers. Green speaks to the microaggressions she is constantly subjected to as a writing center director (23-25). Structurally, the racism she describes is tied to the professional environment of her institution, while writing center studies’ whiteness is emphasized more broadly by the fact that she “was the first Black person to have the keynote platform in the 34-year history of the [IWCA] conference” (15). Nanton writes from a tutor’s perspective about the sexist and racist verbal abuse she suffered in the writing center, resulting in her “dismissal/resignation” as an undergraduate tutor.

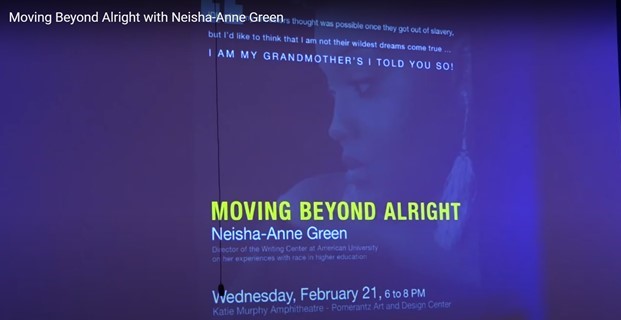

Every writing center professional should read or listen to Green’s keynote (Figure 3) and read Nanton’s story in the context of writing center wellness scholarship. Both women speak to the pressures of writing center work that marginalized workers suffer across academic status. If caring for oneself is an act of political warfare, as Lorde argues, the stakes of writing center wellness become even larger in scale. Any scholarship on wellness must be active in addressing the oppressions our workplaces perpetuate as products of structural, historical, and institutional inequities. Wellness cannot be the sole responsibility of the individual to survive oppression within scholarly and professional spaces. Any scholarship on wellness must be active in addressing the oppressions our workplaces perpetuate as products of structural, historical, and institutional inequities. Wellness cannot be the sole responsibility of the individual to survive oppression within scholarly and professional spaces. As Green writes, “I want more than just alright—and right now, I’m not alright, because y’all keep trying me” (23). She writes on the way her professional and personal behavior depends on contexts she has learned to navigate “as a tutor, then a Black tutor … a writer, then a Black writer” differentiating, “When I am not in self-care, / self-defense, or / ‘Oh Lord not me today’ mode” (Green 23). Nanton’s own experience of violent toxicity in the writing center will linger in our field’s scholarship, but more significantly, it will persist in her life:

What I have experienced at this writing center, I now will take with me for the rest of my life, to every job I have, and this will sadly more than likely never change. I will almost always feel as though I cannot trust my co-workers, or my bosses, particularly with personal or even workplace grievances. (Haltiwanger Morrison and Nanton)

Writing centers are key spaces of professionalization and mentorship for many student workers. They can inculcate racism and patriarchal violence early in an academic career, as with Nanton, and reify those same oppressions well after someone has worked their way up the ladder, as with Green. Both writers speak to the discriminatory stresses they experience, showing the reality that wellness for marginalized workers is a matter of survival and empowerment. In contrast to the ways that resilience places the responsibility on the oppressed to individually overcome structural violence, these writers place responsibility on writing center practitioners to make more livable professional and scholarly spaces.

I’d like to return to the question I posed at the start of this essay: what oppressions necessitate wellness and how can we name and resist them? In their writing, Green as well as Haltiwanger Morrison and Nanton make the answer clear. The most marginalized of us are already speaking to the oppressions we experience. Multiple marginalized scholars like Green, Haltiwanger Morrison, and Nanton name and work to resist said oppressions. Wellness can be the next step, where we work towards “moving beyond alright” (Green 23), and where we step even further into building alternatives to institutional structures that beget oppression. Based on the activist history of self-care, I posit four principles for community wellness in the writing center. It is my hope that we form a more radical relationship with our work at this early stage of our field’s wellness scholarship.

Principle 1: Connect wellness to local activist and community health programs

Wellness in the writing center is intertwined with broader networks of care in university services; however, we must hold space to discuss the real limitations of those services, their need of revision, and the community-based alternatives that can be cultivated and supported. Holding space means that we disrupt top-down forms of professional development to create opportunities for workers to share experience and expertise with aspects of the institutional structures they inhabit. That institutions have barriers to university services is not a new insight to writing center professionals, given research into the barriers that writing centers themselves have between their services and marginalized populations (Salem). Yet, oft-cited writing center scholarship on mental health (Degner et al.; Perry) points to university services without attending to the violence and inaccessibility those spaces present to first-gen, queer, international, and minority students who work at the writing center.

We cannot only look and work inward; wellness in the writing center must reckon with our position in universities writ large, contending with universities’ material conditions and broader issues of labor, discrimination, and care. We cannot only look and work inward; wellness in the writing center must reckon with our position in universities writ large, contending with universities’ material conditions and broader issues of labor, discrimination, and care. Fifty-seven percent of counseling program directors report they lack the hours to meet student needs. The average wait for university students to receive support is 17.7 days on a waitlist—that is, for the 33.7% of centers that have a waitlist to begin with (LeViness et al. 2). Arguing that writing centers partner with campus services, as both Degner et al. and Perry suggest, is an important first step. However, doing so uncritically—without attending to disparities of access and to the material conditions of local campus services—can be inconsiderate of marginalized workers’ vulnerability at best, and a danger to their wellbeing at worst if they are directed to services that cannot meet their needs.

Institutional support as it currently operates is not a viable source of care for many students, and so writing centers can list forms of local support for staff and connect with community organizations to provide alternatives to university resources. While local resources are supplementary to institutional support within the university for some, they are vital alternatives for students who require networks of community care outside the discriminatory structures of the university. There are often deep material disparities between universities and the communities they are located in, so in highlighting community support organizations, writing centers should not simply exacerbate often limited community resources to fill a university gap of support. While marginalized student workers need support, whether from within or outside of their university, writing centers should not be complicit in passing responsibility for care from universities onto local communities. Monetary support, volunteer work, and building community literacy partnerships funded by host universities are just a few examples of the ways writing centers can practice reciprocity with community support organizations.

Professional development and wellness training in the writing center can discuss the limitations of campus counseling and other student services, including material limits such as inaccessible wait times and the representational limits of whiteness, class, and normativity cited throughout this piece. Writing center professionals can hold space in our centers themselves to share campus initiatives for change, connecting writing center wellness to student/worker activism. At institutions ranging from the University of California at Berkeley to the University of Kansas, students have organized and struggled for mental health resources to support students of color (New). By raising awareness of local activist initiatives, writing centers can support larger forms of change within their universities and communities, advocating for better systems of support for marginalized students. Grappling with disparities in support turns us toward the larger context of wellness in the writing center—what makes it necessary and what institutional forces hinder its support structures.

Principle 2: Contextualize wellness in terms of and in resistance to institutional ableism

Writing center professionals must deploy wellness practices critically, not just to react to limited wellness resources under university austerity, but to be proactive against the ways that wellness has historically been leveraged to reify ableist notions of ability in the workplace (Bagenstos). Situating community wellness in terms of writing center work means we must contextualize our practices in the larger institutions that house our work. Disability is necessarily implicated in any discussion of professional wellness, given problematic relations between individual responsibility, productivity, and health in the workplace. As such, this principle is meant to give ableism its own focus—interconnected with other oppressions, but especially pertinent to the ways wellness can exclude or ignore lived experiences of disabled workers. Ableism is broadly defined as an orientation toward disability as “abject, invisible, disposable, less than human, while able-bodiedness is represented as at once ideal, normal, and the mean or default” (Dolmage). In the context of higher education, however, this definition is further whetted to include the ways in which academic structures are designed—what Jay Dolmage defines as academic ableism.

As writing center scholars have pointed out (Babcock and Daniels, Daniels et al.), our work is in no way excluded from the ableist practices of assignment deadlines, attendance, or even the inaccessibility of our centers themselves. This same point holds true for disabled writing center workers, inviting us to examine our professional development in general, and wellness in particular, for any capitulation to ableism. Writing centers are not separate from university austerity, institutional ableism, or other forms of oppression that are often directly enacted in structures of university administration and service (Strickland; Welch and Scott). Professional development that foregrounds workplace solidarity can position self-care as an anti-ableist approach to wellness and also foreground the interconnectedness of writing center labor and resistance. Put another way, wellness should not just be ‘not ableist,’ for example, by ensuring that wellness practices like meditation (Featherstone et al.; Mack and Hupp) are inclusive, accessible, and voluntary for disabled and non-disabled workers. These practices should also be anti-ableist—they should point out the ableist ways wellness and health can be linked to productivity and instead make space for alternative definitions. Consultants and administrators alike should challenge why is wellness important? Who is it important for? Why is it necessary? Is it just to make us all more productive, and if so, who does that benefit? Who does it exclude? How do we practice wellness to support one another? Why do we need to support one another in the first place?

Consultants and administrators alike should challenge wellness initiatives by asking:

- Why is wellness important?

- Who is it important for?

- Why is it necessary?

- Is it just to make us all more productive, and if so, who does that benefit?

- Who does it exclude?

- How do we practice wellness to support one another?

- Why do we need to support one another in the first place?

Disability studies in writing center scholarship must be brought to bear upon the ableism and inaccessibility that wellness can reify. Texts written by disabled writing center scholars, like Kerri Rinaldi’s “Disability in the Writing Center,” can contextualize writing center wellness alongside broader conversations of writing center work to address institutional ableism in the ways we interact with writers and workers alike. Work from outside the writing center grapples directly with the ableist tendencies of wellness in workplaces (Basas; Kirkland) and more broadly engages with inaccessibility within institutions like the university (Minich). Furthermore, any notion of disability justice must be intersectional, resisting the ways that disability is often whitewashed in scholarship (Bell) and resisting the lack of support for disabled workers of color. Disability studies texts like Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha and work by Jina Kim and Sami Schalk build on conversations about care and the methods with which we confront and redress ableism and racism as linked structures of oppression. This principle and the texts listed above are intended to initiate a discussion of anti-ableism in writing center wellness scholarship. We can begin to alter our practices by citing outside the borders of our own literature and amplifying the histories of oppression that make wellness and care necessary in the first place.

Principle 3: Develop wellness through antenarrative and experiential scholarship

In professional development, writing center workers can be encouraged to amplify the perspectives of marginalized scholars, complicating what we think about as the key scholarship that informs our practices. Antenarrative is an applicable type of retrospection and speculation theorized for professional spaces. Jones et al., citing David Boje’s 2011 definition of antenarrative, writes that:

In contrast to narratives, which Boje conceived as characterized by ‘stability and order and univocality’ (5), antenarratives are poly-vocal, dynamic, and fragmented—yet highly interconnected. They link the static dominant narrative of the past with the dynamic ‘lived story’ of the present to enable reflective (past oriented) and prospective (future oriented) sense making. (Jones et al. 2)

This method has been applied to both professional and managerial settings (Boje) and to professional writing scholarship (Jones et al.) as a way to disrupt normative histories of practice. By examining the history of writing center scholarship and looking beyond our grand narratives, student workers can amplify the work of queer, disabled, and minority voices that apply to our notions of wellness—whether directly from our discipline, or from other fields of study. We can apply these scholarly perspectives in local training modules and other forms of professionalization, setting the stage for the work that has already been done within and beyond our field. This same methodology can expose exigencies where our scholarship lacks the perspectives of many writing center workers and must be expanded to more fully represent the diversity of experiences that inform and complicate our work.

Where antenarrative reframes the past, experiential scholarship can push our discipline into new ways of doing and caring that would otherwise be obscured by institutional norms. In a tutor column for the South-Central Writing Centers Association, Shantel Buggs theorizes how experiential knowledge could frame writing center consultations. Drawing from standpoint theory in Black feminist thought, Buggs asks, “how can students of color feel comfortable in the writing center, and how can the writing center encourage these students to embrace their own epistemological standpoints?” (23). As with students’ writing experiences, writing center workers’ needs for wellness are intertwined with their positionality and identities. This principle directly takes up and amplifies the calls to action women of color have made and modelled with their own stories in writing center studies. In their piece from 2017, Wonderful Faison and Anna Treviño suggest shifting writing center practice according to “the experiences of historically marginalized bodies working and receiving assistance/services in the WC.” Haltiwanger Morrison and Nanton similarly call for this shift to draw on “the voices and experiences of tutors of color to inform the practices and scholarship of our field.” Experiential knowledge reveals the political dimensions of our work that we often obscure: challenging, revising, and reclaiming writing center practice towards a more livable and just end.

Larger-scale studies can require methods training beyond what writing centers can offer in professional development to their workers. To disrupt our grand narratives in ways that can be accessible and materially feasible, writing centers must amplify marginalized workers’ experiential knowledge. Knowledge from outside of writing center scholarship can also offer perspectives that intervene in wellness and care. Counseling, social work, women and gender studies, linguistics, education, and many more fields are outside of writing center studies, but often are embodied and represented in our centers’ staff and should be amplified in our wellness work. Our scholarship is often characterized by an “inward gaze” and “tight-knit genealogy,” as Neal Lerner put it in his analysis of the Writing Center Journal (68). Our homogeneity is in the way we cite so adamantly from within our field, but I argue it is also apparent in which conversations we cite marginalized writing center scholars. Wellness can be a topic in which we emphasize a diverse, outward-facing perspective from conventional writing center knowledge. Workers bring disciplinary and experiential perspectives that, when paired with knowledge of what has already been done, afford insight into what needs to be done next.

Professional development can and should inform local practices and broader scholarly conversations from the perspectives of those who are otherwise not often cited in writing center scholarship. Respecting the diversity of a writing center’s workforce goes beyond quantitative data—the experiences within must inform how wellness is encouraged and addressed. What is needed is a system of accountability to respect and amplify marginalized workers’ epistemologies and experiences. Only by committing to accountability can practices like antenarrative and experiential knowledge-making be ethically organized towards inclusive community wellness.

Principle 4: Position wellness within a pedagogy of care

Calling for resources, accessibility, antenarratives and experiential knowledge from vulnerable workers, including tutors and directors, risks placing a burden on members of the communities that wellness is meant to support. Thus, it is necessary to frame all three previous principles in terms of a pedagogy of care in writing center wellness. In her article “Pushback,” Ersula Ore writes about her interactions confronting and questioning white students’ microaggressions in the everyday spaces of the university. On her role as a professor, she argues, “those of us resting at the intersection of multiple forces of oppressive service, and those of us who are not, take into account the ways in which histories reverberate and intersect in academic space” (28). Her piece frames transgressions of students’ etiquette and challenges to students’ assumptions and privilege as caring interventions. She is caring for students who will not otherwise see how they reify oppression when she confronts and educates them. Ore concludes that she is also caring for herself as a woman of color whose professional belonging is constantly under doubt in ways that she experiences as intersectional oppressions.

Ore speaks to the professional tensions of her role as an educator and her need to protect and care for herself—a tension patently applicable to writing center work as well.

Green directly cites her experiences as a director facing the same oppressions as a Black female academic. Recounting instances of colleagues berating her about what her “qualifications were for doing this work,” she writes, “”microaggressions have been tattooed on my soul and branded in my mind” (23). At her own institution, Ore is asked if she “works here” in the elevator to her academic building; Green is harassed in her car, asked if she “had any business on campus” (Ore 9; Green 24).

Both Green’s and Haltiwanger Morrison and Nanton’s pieces work as forms of pushback against white supremacy in writing center studies. Like Ore, they engage in experiential knowledge-making that informs writing center scholarship as well as model ways to produce knowledge within and about writing centers locally. Addressing wellness means engaging in care practices that respond to the inequities that emerge in writing center work at both local and disciplinary levels. A pedagogy of care in the writing center means that no worker should be asked to inform on their community or to act as tokenized figures in research and wellness practices. From experiential scholarship and antenarrative to community networks of support, writing centers should hold space for workers to share connections, but never place the burden of making wellness inclusive on those who are meant to benefit most from its practice. As Ore writes, citing Fannie Lou Hamer, “there comes a point where one becomes ‘sick and tired of being sick and tired’” (29). A pedagogy of care intervenes before writing center workers reach “a point where silence and acquiescence to gendered scripts, hierarchies of discipline, and customary performances of the color line” have the exact opposite effect intended by wellness (Ore 29). By ensuring that writing center wellness does not rely on vulnerable workers overextending themselves to create change, a pedagogy of care enacts a constantly reflexive relationship between workers and wellness. We must check and recheck our practice to ensure that we are caring of and accountable to one another. Care can be abrasive. It can make people uncomfortable as it shakes and unsettles institutional norms of behavior. These are features of a political framework of wellness informed by experiences of oppression and resistance to its continuity. We must recognize, as Ore does, that pushback can be a way to care for oneself and others; that wellness is both politically resistant and proactive in creating change. Care can be abrasive. It can make people uncomfortable as it shakes and unsettles institutional norms of behavior. These are features of a political framework of wellness informed by experiences of oppression and resistance to its continuity.

Conclusion

Under a pedagogy of care, principles of community wellness work to address the scholarship already being done on wellness in the writing center, including those adjacent in this digital edited collection. The ways we implement empirical scholarship into our professional practices are always political, expressing some values over others through the communities and traditions we evoke and groups who benefit as a result. The principles presented in this article are not just a means to produce new knowledge, but to re-contextualize extant scholarship. We must grapple with the values we express as a field when we discuss wellness, and work to apply anti-racist and anti-ableist frameworks in all of our scholarly conversations. If we enact wellness practices by contextualizing and resisting institutional oppressions that necessitate its practice in the first place, we can hold ourselves accountable to the most vulnerable of our communities.

This essay is as much a tool for administrators designing resources as it is a guide for workers to resist uncritical wellness practices. There is nothing in the phrasing of the above principles that precludes tutors or graduate administrators from cultivating community wellness in the writing center. It is my hope that this essay might help writing center administrators ally with and support their workers, especially as many directors themselves occupy precarious labor positions (Caswell et al.) and experience oppression as queer, disabled, minority, or otherwise marginalized academics (Green). Directors, consultants, and staff can all build solidarity to contextualize material conditions rather than stratify wellness along managerial lines. However, as is so often the case, it will be workers who carve out livable spaces for community and form coalition in the writing center.

As wellness takes on greater importance as a part of writing center training, workers can be critical of ableist notions of health and productivity. Where university administrations advertise overburdened counseling services, workers can consider the needs of our coworkers and connect with community actions and resources we are aware of, and often organize ourselves. Workers can push back in training when the material issues of funding and representation within university services are glossed over. This is the activist history of wellness—not managerial edicts, but collective, local acts of resistance and care backed by principles that can be taken up by our whole field and applied according to local contexts. If administrators seek to implement equitable wellness practices, they must do so as workers first and foremost—as peers to staff members and tutors with shared goals that will, at times, conflict with university administration as we build solidarity with one another. We are all accountable to one another when we seek to make wellness an ongoing and constantly revised aspect of writing center practice.

Works Cited

Archive on Demand. “Moving Beyond Alright with Neisha-Anne Green.” YouTube, keynote by Neisha-Anne Green, 30 May 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y6szZCwGFiU

Babcock, Rebecca Day, and Sharifa Daniels. Writing Centers and Disability. Southlake, Texas: Fountainhead Press, 2017.

Bagenstos, Samuel R. “The EEOC, the ADA, and Workplace Wellness Programs.” Health Matrix, vol. 27, no. 1, 2017, pp. 81-100.

Bassas, Carrie Griffin. “What’s Bad About Wellness? What the Disability Rights Perspective Offers About the Limitations of Wellness.” J Health Polit Policy Law, vol. 39, no. 5, 2014, pp. 1035–66.

Bassett, Mary. “Beyond berets: the Black Panthers as health activists.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 106, no. 10, 2016, pp. 1741-43. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5024403/

Bell, Christopher. “Introducing White Disability Studies: A Modest Proposal.” The Disability Studies Reader. 2nd ed. Ed. Lennard J. Davis. New York, NY: Routledge, 2006, pp. 275–82.

Boje, David. M. Storytelling Organizations. London, England: Sage, 2008.

Buggs, Shantel G. “Experiential Knowledge in the Writing Center: From a Black Feminist Perspective.” South Central Writing Centers Association Annual Meeting, Oklahoma State University, 2014.

Carey, Tamika. Rhetorical Healing: The Reeducation of Contemporary Black Womanhood. New York: SUNY Press, 2016.

Caswell, Nicole, et al. The Working Lives of New Writing Center Directors. UP of Colorado, 2016.

Cavounidis, Costas, and Kevin Lang. “Discrimination and Worker Evaluation. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 21612.” NBER, 2015. https://www.nber.org/papers/w21612

Daniels, Sharifa, et al. “Writing Centers and Disability: Enabling Writers Through an Inclusive Philosophy.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 2015. http://www.praxisuwc.com/daniels-et-al-131

Degner, Hillary, et al. “Opening Closed Doors: A Rationale for Creating a Safe Space for Tutors Struggling with Mental Health Concerns or Illnesses.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 2015. http://www.praxisuwc.com/degner-et-al-131

Dolmage, Jay. Academic Ableism: Disability and Higher Education. U of Michigan P, 2017.

Dyrbye, Liselotte, et al. “Race, ethnicity, and medical student well-being in the United States.” Archives of Internal Medicine, vol. 167, no. 19, 2007, pp. 2103–09. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/413324

Erevelles, Nirmala. “Race.” Keywords for Disability Studies, edited by Rachel Adams and Benjamin Reiss, New York UP, 2015, pp. 145–48.

Faison, Wonderful, and Anna Treviño. “Race, Retention, Language, and Literacy: The Hidden Curriculum of the Writing Center.” The Peer Review, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017. http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/race-retention-language-and-literacy-the-hidden-curriculum-of-the-writing-center/

Featherstone, Jared, et al. “The Mindful Tutor.” How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019. https://wlnjournal.org/digitaleditedcollection1/Featherstoneetal.html

Fitch, Bob. “Black Community Survival Conference, March 30th, 1972. Bobby Seale.” Bob Fitch photography archive – Black Panther Party, Oakland, California, Stanford Digital Repository, 30 Mar. 1972, https://purl.stanford.edu/pj821gy9714

Fitch, Bob. “Black Community Survival Conference, March 30th, 1972. Sickle cell anemia testing.” Bob Fitch photography archive – Black Panther Party, Oakland, California, Stanford Digital Repository, 30 Mar. 1972, https://purl.stanford.edu/zq284sv2015.

Green, Neisha-Anne. “Moving beyond Alright: And the Emotional Toll of This, My Life Matters Too, in the Writing Center Work.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 37, no. 1, 2018. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26537361?seq=1

Haltiwanger Morrison, Talisha M., and Talia O. Nanton. “Dear Writing Centers: Black Women Speaking Silence into Language and Action.” The Peer Review, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019. http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/dear-writing-centers-black-women-speaking-silence-into-language-and-action/

Harris, Aisha. “How ‘Self-Care’ Went From Radical to Frou-Frou to Radical Once Again.” Slate Magazine, 5 Apr. 2017. http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2017/04/the_history_of_self_care.html

Hyun, Jenny. K., et al. “Graduate student mental health: Needs assessment and utilization of counseling services.” Journal of College Student Development, vol. 47, 2006, pp. 247–66.

Jenkins, Susan. “Community Wellness: A Group Empowerment Model for Rural America.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, vol. 1, no. 4, 1991, pp. 388-404. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/267727/pdf

Jones, Natasha. N., et al. “Disrupting the past to disrupt the future: An antenarrative of technical communication.” Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 25, no.4, 2016, pp. 211–29. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10572252.2016.1224655?journalCode=htcq20

Kim, Jina. “Toward a Crip-of-Color Critique: Thinking with Minich’s ‘Enabling Whom?’” Lateral: Journal of the Cultural Studies Association, vol. 5, no.1, 2016. https://csalateral.org/issue/6-1/forum-alt-humanities-critical-disability-studies-crip-of-color-critique-kim/

Kirkland, Anna. “Critical Perspectives on Wellness.” J Health Polit Policy Law, vol. 39, no. 5, 2014, pp. 971–88.

Kennedy, Stephen D., and Stanley B. Baker. “School counseling websites: Do they have content that serves diverse students?” Professional School Counseling, vol. 18, no.1, 2014, pp. 49-60. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/School-Counseling-Websites%3A-Do-They-Have-Content-Kennedy-Baker/a7359e1458188f6e5200ab16cdd9d8dced38d96e

Lemke, Thomas. “’The Birth of Bio-Politics’: Michel Foucault’s Lecture at the College de France on Neoliberal Governmentality.” Economy and Society, vol. 30, no. 2, 2001, pp. 190-207.

Lerner, Neal. “The Unpromising Present of Writing Center Studies: Author and Citation Patterns in ‘The Writing Center Journal’, 1980 to 2009.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 34, no. 1, 2014, pp. 67–102. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43444148?seq=1

LeViness, Peter, et al. “The Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors Annual Survey Public Version 2018.” AUCCCD, 2018.

Lorde, Audre. A Burst of Light: and Other Essays, Ixia Press, 2017.

Mack, Elizabeth, and Katie Hupp. “Mindfulness in the Writing Center: A Total Encounter.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, Spring 2017. http://www.praxisuwc.com/mack-and-hupp-142

Maton, Kenneth. I., et al. “Experiences and perspectives of African American, Latina/o, Asian American, and European American psychology graduate students: A national study.” Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, vol. 17, 2011, pp. 68 –78. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3711504/

Minich, Julie Avril, “Enabling Whom? Critical Disability Studies Now” Lateral: Journal of the Cultural Studies Association, vol. 5, no.1, 2016. https://csalateral.org/issue/5-1/forum-alt-humanities-critical-disability-studies-now-minich/

McKinley, Christopher J., et al. “Reexamining LGBT resources on college counseling center websites: An over-time and cross-country analysis.” Journal of Applied Communication Research, 43(1), 2015, pp. 112–29. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00909882.2014.982681

Nelson, Alondra. Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight against Medical Discrimination. U of Minnesota P, 2013.

New, Jake. “Students demand more minority advisers, counselors.” Inside Higher Ed. 14 Jan. 2016. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/03/03/students-demand-more-minority-advisers-counselors

Ore, Ersula. “Pushback: A Pedagogy of Care.” Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, vol. 17, no. 1, 2017, pp. 9-33. https://read.dukeupress.edu/pedagogy/article-abstract/17/1/9/20496/PushbackA-Pedagogy-of-Care?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Perry, Alison. “Training for Triggers: Helping Writing Center Consultants Navigate Emotional Sessions.” Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016. http://compositionforum.com/issue/34/training-triggers.php

Rinaldi, Kerri. “Disability in the Writing Center: A New Approach (That’s not so New).” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 2015. http://www.praxisuwc.com/rinaldi-131

Ryan, Leigh, and Lisa Zimmerelli. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Salem, Lori. “Decisions… Decisions: Who Chooses to Use the Writing Center?” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 2, 2016, pp. 147-71. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43824060?seq=1

Schalk, Sami. “Critical Disability Studies as Methodology.” Lateral: Journal of the Cultural Studies Association, vol. 5, no.1, 2016. https://csalateral.org/issue/6-1/forum-alt-humanities-critical-disability-studies-methodology-schalk/

Skovholt, Thomas. M., and Michelle Trotter-Mathison. The Resilient Practitioner: Burnout prevention and Self-Care Strategies for Counselors, Therapists, Teachers, and Health Professionals. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. 2011.

Stamm, Beth Hudnall. Secondary Traumatic Stress: Self-Care Issues for Clinicians, Researchers, and Educators. Baltimore, Maryland: The Sidran Press. 1995.

Stebleton, Michael J., et al. “First‐Generation Students’ Sense of Belonging, Mental Health, and Use of Counseling Services at Public Research Universities.” Journal of College Counseling, vol. 17, no. 1, April 2014, pp. 6-20. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2014.00044.x

Strickland, Donna. The Managerial Unconscious in the History of Composition Studies. Southern Illinois UP, 2011.

Welch, Nancy, and Tony Scott. Composition in the Age of Austerity. UP of Colorado, 2016.