6 Tutors as Counselors: Fact, Fiction, or Writing Center Necessity by Sarah Brown

Keywords: Motivational interviewing, mental health, writing tutors, psychotherapy, evoking, tutor training

Introduction

In this chapter, I examine contemporary counseling techniques—particularly William R. Miller and Stephen Rollnick’s motivational interviewing (MI) technique as described in their book Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change—as they relate to writing center practice and tutor training methods. In doing so, I propose ways that writing centers have the potential to provide both academic help and emotional support to students in their tutoring sessions.

My motivation for writing this chapter stems from personal experience at my university’s writing center, both as a tutor and a writer. As a graduate student tutor, I feel confident in my qualifications, training, and ability to assess my client’s needs. Although the emotionally overwhelmed client is rare, I have had a few experiences with them. Disappointed by my lack of training on how to respond to an emotionally overwhelmed client, I felt that what little advice I did give was, unfortunately, inadequate. Disappointed by my lack of training on how to respond to an emotionally overwhelmed client, I felt that what little advice I did give was, unfortunately, inadequate. For example, I had a doctoral student share how her somewhat tempestuous relationship with her advisor had manifested throughout the dissertation writing process. She described their interactions in-depth and discussed the emotional turmoil those interactions had caused her. She spoke about the anxiety she experienced when communicating with her advisor by email. And, naturally, she expressed how anxious she was to revise her work and share it with an advisor whom she respected but feared because of their incompatibility. This particular session was emotional, not only because of what she shared, but also because I felt an emotional response to her struggle and an overwhelming pressure to be the person to resolve this issue for her. In the same semester, a freshman client asked for help on how to begin her essay. She had not conducted any research or chosen a topic. Our conversation was difficult because of her lack of effort, but she later confessed that she was incredibly homesick. Although she never explicitly described a connection between her homesickness and her procrastination with the project, I believe there was one. She was clearly stressed, overwhelmed, and seeking guidance of a particular kind, and I realized I was unequipped to give her the advice she needed.

As a result of these emotional experiences, I began conducting research for this chapter with these writers in mind. I wanted to discover techniques that would have made disheartened writers like these feel more confident and develop a plan for how to help future writers address their personal challenges. In my experiences as a writer, too, I realized how emotional a writing center session can be. For some students, writing center sessions can become emotional when outside problems are affecting a writer’s wellbeing.

Mental health concerns have risen recently among graduate students, affecting both writing center tutors and writers at institutions that serve graduate writers and/or that are staffed with graduate writing tutors (Kruisselbrink 1; Morrish 13; Tinklin et al. 495). In current writing center practice, there are few techniques tutors are trained to use to inform, support, and provide guidance for writers who are facing mental health concerns like stress and anxiety. And the methods that are sometimes used—which typically include informing the writing center director or referring the student to counseling services—have the potential to disregard the student’s ability to incite personal change in themselves, as well as the material circumstances of an institution’s therapeutic support. After researching the connection between humanistic psychology and the writing center, I propose the incorporation of Motivational Interviewing into tutor training, and I suggest how it could be used as a supportive method in sessions with emotional writers. Although I believe in the potential effectiveness of MI, especially for tutor training, I have not had the opportunity to practice it myself before graduating; therefore, this is an exploratory chapter that I hope other scholars will put into practice.

Literature Review

As a graduate student, I know all too well the difficulty of balancing my academic life and my personal life. Graduate students and undergraduate students often experience stress related to their multiple roles. Additionally, it is important to recognize the ways in which writing center practices resemble those in psychology. Christina Murphy analyzes the similarity between tutoring and therapy and claims that usually “the people who enter in therapy are ‘hurt’—they are suffering from negative feelings or emotions, interpersonal problems, and inadequate and unsatisfying behaviors” (14). Murphy draws parallels between people who seek therapy and those who seek writing center support:

The same is often true of individuals who come to a writing center. They, too, are “hurt” in that they display insecurities about their

abilities as writers or even as academic learners, express fear to the tutor that they will be treated in the same judgmental or abusive way that they have been treated by teachers or fellow students before, or exhibit behavior patterns of anxiety, self-doubt, negative cognition, and procrastination that only intensify an already difficult situation. (14)

To emphasize the importance of understanding mental health concerns in the writing center, this section also provides a brief overview of recent studies on mental health issues in educational institutions, focusing on students, tutors, and staff. Thus, this literature review will cover the history of MI to establish some context for the reader and to provide a better understanding of the potential connectivity of MI to writing center work. This overview not only identifies the problem—a lack of training around strategies to use in responding to tutors and students with mental health concerns—but it also offers support for using MI techniques to make writing centers more attuned to the emotional needs of their tutors and writers.

Mental Health Concerns in Tutors and Administrators

Hillary Degner et al.’s study on understanding writing center tutors’ mental health discovered that 57% of writing center tutors (the majority of whom are graduate students in their study) and administrators suffer from some form of mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, and Attention Deficit Disorder (Degner et al.). The study revealed that 56% of the tutors’ and staff’s mental health concerns affected their tutoring abilities. Degner et al.’s study supports my argument for better student mental health awareness in writing center practice, and it also reveals that there needs to be equal awareness of writer and tutor mental health.

Role Strains in Graduate Students/Tutors

Additionally, Rebecca Grady et al. note that graduate students experience role strains because of the different responsibilities and jobs they take on. They note that “the social position of graduate students is rife with chronic role strains—ongoing or repetitive difficulties in meeting role(s) expectations—such as role conflict and role overload. While still students, many are also instructors or in other supervisory roles at their universities cause stress” (5). Role strains often lead graduate students to question their priorities even as they struggle with time management (6). In a study on undergraduate and graduate student’s stress levels and help-seeking behaviors, Sara Oswalt and Christina Riddock identify that stress levels among undergraduate and graduate student populations has increased over the past several decades (25). They also note that graduate students seek mental health support at low levels, even though they might be interested in this kind of support for role conflict and other experiences that contribute to their stress levels (26). We often forget that graduate students are just as likely to experience mental health issues and disabilities as undergraduate students. This mental fatigue is often due to graduate students having to fulfill multiple roles at one time (as teacher, tutor, and student).

Isolation among Graduate Students

Graduate students struggle with more than just role strains; they also experience isolation. In a review of the literature, Jenny K. Hyun et al. found that “although the severity of mental health problems was the greatest predictor of seeking counseling, graduate students were more likely to seek counseling because of their distance from other sources of social support” (249). Yet graduate students also sought support from advisors or peer counselors who were largely unequipped to handle severe mental health concerns (249). Being away from family, friends, and other forms of social support, then, contributes to mental health issues in graduate students and higher education may be largely unequipped to support acute needs. Furthermore, these needs are not new. Mental health concerns can trickle down into writing centers and manifest in the dynamics between graduate writers and tutors Mental health concerns among graduate and undergraduate students is a long-term issue. A 2001 MIT survey reveals that out of its undergraduate and graduate respondents, “74% reported having had an emotional problem that interfered with their daily functioning . . . [and] 35% of students reported a wait of 10 or more days for their initial appointment with the [mental health] service” (MIT Mental Health). A recent study found that “graduate students are more than six times as likely to experience depression and anxiety as compared to the general population” (Flaherty). These findings regarding the high levels of mental health concerns among graduate (and undergraduate) students are compounded by the way educational institutions handle mental health concerns, which includes a lack of appointment availability at their on-site mental health facilities and, for some graduate students, outsourcing of mental health support to entities outside the institution. These mental health concerns, then, can trickle down into writing centers and manifest in the dynamics between graduate writers and tutors.

Motivational Interviewing—A Historical Overview

Miller and Rollnick’s collaboration in their 1991 book Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior is perhaps the first collective example of MI concepts, but its early roots go much further back. According to Theresa Moyers, several psychological approaches influenced MI, primarily client-centered psychotherapy (292). She notes, however, that MI is more heavily influenced by social psychology, emphasizing Brehm and Brehm’s 1981 work in reactance forms, which attempt to determine “the right moment to move forward in suggesting action” with a client (292). This approach came at a difficult time in the field of psychology, when psychologists were experiencing “increasing frustration with the unsubstantiated and clinically unsustainable belief that one should confront and coerce writers to change” (Allsop 343). As Moyers points out, interest in MI and its applications became even more popularized following the publication of Miller and Rollnick’s Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change when its techniques had been circulated (296). Moyers and Miller provide what I believe to be the most accurate definition of this technique: “MI directly addresses what is a very common and often frustrating issue in practice: people’s reluctance to change despite advice to do so” (759). Or, in the case of the writing center session with an emotionally overwhelmed student, a reluctance or inability to change that might be due to a lack of emotional guidance. If tutors were better prepared with appropriate guiding questions that would lead writers toward motivation for personal change, the writing center could provide writers with change-focused approaches that are beneficial for their writing habits and their personal lives.

Defining Motivational Interviewing and Identifying the Connection Between Tutoring and Counseling

MI ultimately encourages the use of self-motivational statements and actions, a practice that can incite positive change in the minds of students struggling with mental health issues, stress, anxiety, and procrastination. Though I have not had the opportunity to use this method in a session, I believe that it could help tutors to manage these kinds of writing center sessions and increase mental health awareness in writing center practice. Thus, I propose that writing centers train their tutors to use the technique of MI for several reasons. Both tutoring sessions and MI sessions are language-based, requiring conversation and collaboration, and both writing center attendees and MI clients are seeking answers, whether for academic or therapeutic purposes. Both tutoring sessions and MI sessions are language-based, requiring conversation and collaboration, and both writing center attendees and MI clients are seeking answers, whether for academic or therapeutic purposes. Both writing center sessions and therapeutic sessions have the opportunity to become forums where behavioral and personal change occur—where writers can recognize their potential as independently-thinking individuals. I recommend writing centers incorporate Miller and Rollnick’s MI therapeutic technique, which involves the following four processes: engaging, focusing, evoking, and planning. Several of these processes resemble those frequently used in writing center sessions, which is why I will emphasize the process I believe is missing from writing center work—evoking. An in-depth discussion of how each process could benefit writing center practice in new ways, however, might be beneficial to include in tutor training as well.

Motivational Interviewing Process

Engaging

Engaging is “the process by which both parties establish a helpful connection and a working relationship” (Miller and Rollnick 26). In a therapy session, this process lays the foundation for a productive relationship between the therapist and the client as the therapist reassures the client of their level of empathy, understanding, and support. Similarly, at the beginning of a tutoring session, one of the tutor’s responsibilities is to lay the foundation for a friendly and productive session and thus utilize the “engaging” process. Doing so requires the tutor to introduce themselves and learn session-related information about the writer (their name, why they have come to the writing center, and what they want to achieve during the session) all while affirming the writer’s strengths and expressing their belief in/support of the writer and their abilities.

Focusing

According to Miller and Rollnick, focusing is the process that determines a “particular agenda” for the session (27). Therapists typically approach this process by negotiating with the client to establish a shared purpose, thus making the client feel both reassured by the therapist’s guidance and confident in their own ability to construct a path toward personal change. Customarily, the writing center tutor is responsible for leading a discussion on what the writer would like to achieve in the session, which establishes a clear direction and agenda for the session as well. Sometimes, the writer volunteers this information, and the tutor does not have to tease it out. It is also worth noting that this “focusing” process sometimes takes place at the beginning of the tutoring session, but it can also take place in other moments. For example, some tutors prefer to read the writer’s text before discussing an agenda for the session. In this motivational technique especially, tutors can become more attentive to their writer’s personal anxieties based on what they determine is the agenda for the session.

Evoking

Evoking, the third process, “involves eliciting the client’s own motivations for change” (Miller and Rollnick 28). In a writing center session, this process would involve the tutor gently exploring why a writer does or does not want to make changes or the writer offering those motivations for change without any probing from the tutor. In many sessions, this process does not take place at all. But when the tutor does attempt this process, they can discover exactly how/where the writer’s personal or writing insecurities lie and thus better guide the writer toward solutions and growth. The use of the MI evoking process could benefit writers facing emotional struggles. Out of the four processes, this technique perhaps requires the most skills, and would thus require the most tutor training in the writing center, because the goal is to help the client determine their own “why” for personal change based on their personal ideas and motivators. A major part of this process, however, is the act of listening and gently exploring the writer’s desire to change. To determine which processes or habits the writer could benefit from changing, the tutor must be willing and capable of asking mutually beneficial questions that allow the writer to recognize their own personal difficulties. It is important for the tutor to make the writer feel heard and valued during this process; it is, however, equally important that the strategy the tutor uses to teach the writer emotional skills will benefit either their writing process or their emotional growth. If, for example, the writer opens up about their emotional concerns, the tutor can acknowledge the statements directly (“I hear you,” “It’s understandable that you feel this way,” etc.) and eventually, but gently, challenge the writer to address those emotions (“If you could change what you are feeling, how would you want to feel?”; “Let’s think of ways we can resolve this,” etc.). Again, implementing this MI technique into a writing center session could allow the tutor to not only become more aware of their clients’ personal struggles, but also equip them with the knowledge and support they need to assess and address those struggles.

Planning

Lastly, the planning process “encompasses both developing commitment to change and formulating a specific plan of action” (Miller and Rollnick 30). In a therapy session, this plan of action is accomplished over time and not always immediately carried out. The therapist encourages the client to commit to a plan for change based on the client’s personal insights. Similarly, tutoring sessions typically conclude with some kind of “takeaway,” such as encouraging the client to return to the writing center, following a more developed strategy like daily dedication to writing exercises, creating an outline before starting the writing process, or developing ways to cope with personal anxieties. Each of these takeaways could give writers motivational guidance toward creating better habits and personal change.

These processes build upon each other. Each process is mutually beneficial because they all serve one particular purpose—encouraging the client to take steps toward change.

Evoking may prove to be the most effective process with an emotionally overwhelmed client because it creates a space for the writer to examine possible reasons for their anxiety or mental block and actively work toward a solution, whether academic or emotional. The “evoking” process begins a process of effective communication. One way for writing center tutors to approach these anxieties is to offer discussion and/or questions that help transform the writer’s anxieties into conquerable tasks.

Some examples of writer anxieties include the following, which are based on my personal experience as a writing center tutor:

- I got a bad grade on this paper and my professor told me to come here.

- I have to write a paper on ___. I have no idea how to start.

- This paper is due at 2:00 p.m. today. Can you help me?

- I’m a really bad writer. Are you good at writing?

Or a student might open up about even more personal emotional struggles they are facing, whether family-related, relationship-related, or academic. For any of these situations, the evoking method has the potential to both comfort the student and encourage them to seek self-motivated ways of overcoming their emotional struggles. In MI therapeutic sessions, this process is quite strategic. Practitioners elicit and respond to change talk, and they also reinforce change talk by following a formula of question, affirmation, reflection, and summary. In a writing center session, I believe tutors should focus on providing affirmation and asking questions, stimulating the writer to consider solutions for personal change.

The following questions or statements might motivate or comfort writers:

- (Affirmation): I really appreciate that you shared this with me.

- (Affirmation): It is OK for you to be feeling this way.

- (Stimulation): Where do you think you could begin if you were to try to change this issue?

- (Stimulation): What could increase your confidence (or punctuality, organizational skills, etc.)?

Sometimes, a tutoring session is centered on helping the writer recognize that seemingly undefeatable tasks can be broken down and overcome. At other times, the writer and the tutor never get to read through the paper because the focus shifts to a conversation about other “life” skills like time management, step-by-step processes such as organization, or ways to improve communication between the student and their instructor. The foundation of Miller and Rollnick’s MI technique involves a conversational interaction, which they define as “a collaborative conversation style for strengthening a person’s own motivation and commitment to change”; this is most likely to occur in the “engaging” process of the session (12). To meet the client’s needs, the therapist and the client must first engage in conversation.

A synchronous (face-to-face) writing center session often:

- begins with a conversation about the assignment (the “engaging” process),

- moves to the client’s ideas about the assignment (either through brainstorming or reading the client’s text, which is the “focusing” process),

- then establishes the agenda for the session (the “evoking” and “planning” processes).

Questions and concerns may be addressed throughout, but an agenda-setting conversation remains the framework for the entire session, no matter what the tutor and the client seek to accomplish. Language and communication, as methods used in both therapy and writing center sessions, serve as the focal point for the majority of face-to-face and individual sessions. As demonstrated by the discussion above, some of these processes already take place in writing center sessions. The evoking method, however, encourages tutors to take an extra step with the emotionally overwhelmed client to establish a safe and self-motivated environment, affirm the client’s emotional needs, and gently encourage self-change.

Training Tutors in Motivational Interviewing—General Guidelines

Writing center directors and/or tutor training instructors will need to familiarize themselves with the MI technique in order to begin incorporating it into their tutor training programs. Due to the sensitive nature of mental health concerns, writing center directors and tutor training instructors might consider partnering with counseling services to prepare for tutor training, in order to learn about the potential challenges that students with mental health issues might face and how to adapt the questioning techniques used by counseling services to tutoring. If writing center directors and tutor training instructors feel unqualified to teach MI techniques, they could reach out to MI practitioners at their home institutions or consult with institutions that utilize these techniques for student support. The directors/instructors could then invite that outside speaker to their tutor training session to discuss incorporating MI into their writing center sessions. Whether it is directors/instructors themselves or a guest speaker who introduces MI into tutor training, they will have to introduce the technique in a practical way that tutors can imitate. Role-playing may be an effective approach. Watching videos of therapists applying MI techniques may be another option for the tutor training session. There are a variety of such videos available on YouTube (Figure 1), particularly on TheIRETAchannel (The Institute for Research, Education and Training in Addictions).

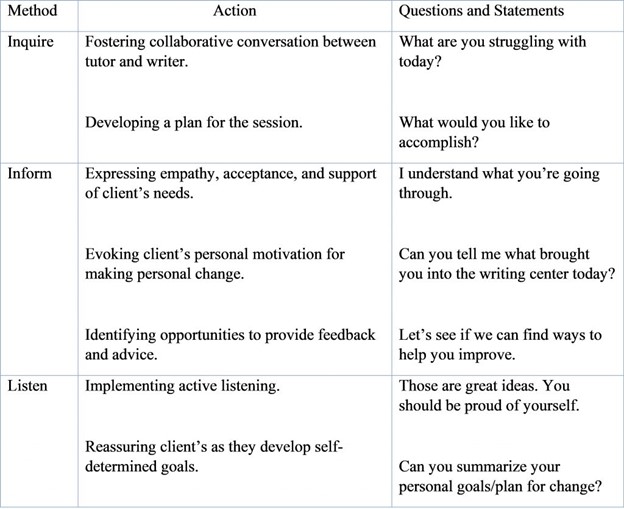

In a video that shares examples of motivational interviewing questions (Figure 2), the therapist uses several MI questions/statements to encourage the client (a woman with a potential drinking problem) to self-motivate. Below, I share a set of questions that aim to self-motivate a client along with a “translation” of each question for how these conversational techniques could be used in a writing center session conversation between tutor and writer.

Self-motivating Questions and Their “Translation” to Writing Center Tutorials:

- Therapist: What is it that you like about alcohol?

- Tutor: Are you confronting any issues with your writing or academic work?

- Therapist: What do you make of this connection between alcohol and stress?

- Tutor: What do you make of the connection between your academic performance and stress?

- Therapist: How have you considered trying to fix this?

- Tutor: How have you considered ways to fix this?

- Therapist: How important is it to you to do something about your drinking?

- Tutor: How important is it to you to work on your academic habits?

- Therapist: How ready are you to do anything right now?

- Tutor: Are you feeling comfortable enough to do something about this right now?

- Therapist: What are some things you could do right now to alleviate your stress?

- Tutor: Can you think of anything we could do right now to alleviate your stress?

After the MI techniques have been introduced to tutors during training, directors and instructors could encourage the tutors to apply the techniques through exercises. Again, I suggest role play where the scenario mirrors the therapy videos introduced during training. Role play gives tutors the opportunity to practice MI techniques that can then be incorporated into future sessions. While MI techniques could be included in a writing center tutor guidebook, so tutors can study them on their own time and/or reference them when necessary, writing center administrators should also prepare for tutor training in MI by reviewing Miller and Rollnick’s book on MI techniques.

A Motivational Tutoring Heuristic

To aid with understanding how to put MI into practice, I have developed a brief motivational tutoring heuristic that includes a guide to incorporating MI techniques into a writing center session. These methods may be applied in the order in which they are listed below or interchangeably throughout the session, depending on the client’s level of personal motivation. The first column describes the method being applied, the second column details what this method entails, and the third column provides conversational sentences or questions the tutor could rely on during the session in order to successfully implement the method.

Table 1

MI Heuristic

Study Limitations

As with every project, there are limitations to incorporating MI into common writing center tutoring practice. I must acknowledge the complicated but necessary balance of utilizing these MI techniques without falling into the role of a counselor. Tutors should be aware, too, that this balance will vary among different kinds of writers and tutoring sessions. I must acknowledge the complicated but necessary balance of utilizing these MI techniques without falling into the role of a counselor. Tutors should be aware, too, that this balance will vary among different kinds of writers and tutoring sessions. Certain writers may abuse the openness of the motivational method and take the direction of the session into unexpected territory, such as discussing intimate personal problems or taking over the session and distracting from the purpose at hand. Additionally, tutors may unintentionally place themselves in the role of a counselor by misusing the method. To prevent the tutor from introducing a “counselor role” into the session, tutors should be familiar with potential negative outcomes of using MI in a writing center session. During tutor training, tutors should be presented with complicated and nuanced situations so that they will be prepared to redirect a real session if it veers into a counseling realm. The dangers of a tutor taking on a counselor role are many, but one that can be more easily addressed is the client becoming too reliant on the tutor. If a tutor begins to feel that the writer is becoming too reliant, the tutor could gently remind the client of the session’s goal or the purpose of the writing center, or suggest they take a break. The tutor can also prevent taking on the role of a counselor by reminding the client of the method’s purpose. Writing center directors, too, can ensure tutors are supported in establishing boundaries in their writing center sessions.

Conclusion

Incorporating MI into tutor training may enhance the way we work with emotionally overwhelmed students. With this training, tutors cannot expect immediate personal change, but they may be able to help writers increase their self-awareness about how their feelings are impacting their ability to complete tasks. Still, we must remember that personal change is hard and often occurs in small steps over a long period of time. Given the increase in emotional needs of students, writing centers need to start thinking about how to support students who are overwhelmed. MI is one strategy writing centers should consider adopting as a tool to support these students.

Works Cited

Allsop, Steve. “What Is This Thing Called Motivational Interviewing?” Society for the Study of Addiction, no. 102, 2007, pp. 343-45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01712.x

Binkley, Collin, and Larry Fenn. “Colleges Struggle With Soaring Student Demand for Counseling.” NBC4 Washington, 25 Nov. 2019. https://www.nbcwashington.com/news/local/colleges-struggle-with-soaring-student-demand-for-counseling/2156039/

Cheung, Yin Ling. “The Effects of Writing Instructors’ Motivational Strategies on Student Motivation.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education, vol. 43, no. 3, Mar. 2018, pp. 55-73. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1174216.pdf

Degner, Hillary, et al. “Opening Closed Doors: A Rationale for Creating a Safe Space for Tutors Struggling with Mental Health Concerns or Illnesses.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, 2015. http://www.praxisuwc.com/degner-et-al-131.

Flaherty, Colleen. “Mental Health Crisis for Grad Students.” Inside Higher Ed, 6 Mar. 2018. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/03/06/new-study-says-graduate-students-mental-health-crisis

Grady, Rebecca K., et al. “Betwixt and Between: The Social Position and Stress Experiences of Graduate Students.” Teaching Sociology, vol. 42, no. 1, 2014, pp. 5-16. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0092055X13502182

Hyun, Jenny K., et al. “Graduate Student Mental Health: Needs Assessment and Utilization of Counseling Services.” Journal of College Student Development, vol. 47, no. 3, 2006, pp. 247-66.

Kruisselbrink Flatt, Alicia. “A Suffering Generation: Six Factors Contributing to the Mental Health Crisis in North American Higher Education.” College Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 1, 2013. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1016492

Miller, William R., and Stephen Rollnick. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York: Guilford Press, 1991.

—. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. New York: Guilford Press, 2012.

Miller, William R., and Theresa B. Moyers. “Motivational Interviewing and the Clinical Science of Carl Rogers.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, vol 85, no. 8, 2017, pp. 757-66.

“MIT Mental Health Task Force Report.” MIT, 6 Nov. 2001. http://web.mit.edu/chancellor/mhtf/

Morrish, Liz. Pressure Vessels: The Epidemic of Poor Mental Health Among Higher Education Staff. London: Higher Education Policy Institute, 2019. https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2019/05/23/pressure-vessels-the-epidemic-of-poor-mental-health-among-higher-education-staff/

Moyers, Theresa B. “History and Happenstance: How Motivational Interviewing Got Its Start.” Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, vol. 18, no. 4, 2004, pp. 291-98.

Murphy, Christina. “Freud in the Writing Center: The Psychoanalytics of Tutoring Well.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 10, no. 1, 1989, pp. 13–18.

Oswalt, Sara B., and Christina C. Riddock. “What to do about being overwhelmed: Graduate students, stress and university services.” College Student Affairs Journal 27.1 (2007): 24-44. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ899402

Tinklin, Teresa, Sheila Riddell, and Alastair Wilson. “Support for Students with Mental Health Difficulties in Higher Education: The Students’ Perspective.” British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, vol. 33, no. 4, 2005, pp. 495-512. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.571.7593&rep=rep1&type=pdf