5 Cultivating an Emotionally Intelligent Writing Center Culture Online by Miranda Mattingly, Claire Helakoski, Christina Lundberg, & Kacy Walz

Keywords: Emotional intelligence, organizational culture, training, online writing centers, writing center culture, remote work

Introduction

Emotional intelligence (EI) is commonly understood as an indicator of one’s ability to identify and respond to emotional behaviors within oneself and others. This emphasis on individual competency can obscure the significant ways group members’ EI shapes and defines organizational culture. Organizational culture resists overt articulation, asserts Edgar Schein in Organizational Culture and Leadership, but manifests concrete expression through individuals’ shared behavioral and attitudinal reactions (Figure 1). Organizational culture finds expression through the values and underlying assumptions groups of individuals draw upon when they encounter similar situations and problems within an environment. For example, when tutors feel comfortable expressing uncertainty about emotional or stressful appointments and are compassionately recognized for their student-centeredness and desire to enhance their instructional approach, it reveals a piece of that center’s organizational culture. Likewise, if staff are encouraged to stay informed on current writing center scholarship but lack time, energy, or confidence to apply these principles to their work, it reveals important information about whether tutors are flourishing within that center’s culture. These emotional responses and the underlying values and assumptions that inform them are central to an organization’s culture. When expressed and reified across individuals’ common experiences, they reflect an accepted understanding of how that organization culturally reacts to the stress and success of daily interaction. Staff members’ emotional responses to their work, environment, and team dynamic reveal how a center’s culture is collectively understood. As such, cultivating EI also cultivates a healthy organizational culture.

In this chapter, we examine EI’s role in creating a healthy writing center culture, where staff feel confident responding to what Arlie Hochschild would call the emotional labor of writing center work. Specifically, we focus on how a year-long EI training series enabled our team to identify the emotional challenges of writing center work and how we could healthfully manage this labor through a culture of connectedness, empathy, and trust. By taking this approach, we combine the practice of understanding individual emotional intelligence with organizational culture theory’s concentration on collective behavioral response to draw attention to a new way of understanding EI’s importance and application to writing center work—one that is rooted in its impact on organizational culture.

We start our chapter with an examination of how organizational culture has been defined in writing center scholarship and theory before turning to highlight the often-overlooked role EI plays in organizational culture. We reflect on the organizational challenges our center faced when it doubled in size and became fully remote, the context in which our training emerged. We demonstrate how EI was essential to our staff’s ability to process larger organizational changes that impacted our team’s connection and communication. We then move to outline our training’s overall design and progression—a twelve-part series scaffolded to increase tutors’ awareness of the individual, interpersonal, and organizational applications of emotional intelligence—as well as its concentration on key EI attributes needed to engage with emotional labor’s different layers, such as self-perception, interpersonal communication, adaptability, decision-making, and stress management. We close with an evaluation of our training’s impact on our staff’s understanding and use of EI while keeping an eye to what these responses reveal about our center’s organizational culture. We highlight important developments in our team’s connectedness, including increased empathy, trust, and intention to assume the best in others, and tie this growth to both the shared training experience and our larger organizational efforts to make EI a foundational feature of our writing center culture. In conclusion, we advocate for a continued commitment to understanding writing center work and labor through the lens of EI and organizational culture.

Throughout this chapter, we aim to contribute to the growing research on wellness and self-care in writing center work through special attention to EI’s application in online settings. Genie Giaimo, for example, acknowledges awareness of self-care practices in writing center communities is growing but notes that existing studies, like those dedicated to mindfulness and mental health (Mack and Hupp; Degner et al.), are few and far between. We seek to address this gap by calling attention to EI training in online environments where clear communication and effectively reading others’ affects are especially challenging and can produce additional emotional labor for students, staff, and administrators alike. Beth Hewett and Rebecca Martini highlight similar concerns about writing program administrators and tutors feeling less prepared for online than face-to-face work. The Conference on College Composition and Communication has stressed the need to train and develop the professional writing community for effective online writing support (Figure 2).

In the wake of COVID-19, this need to understand the emotional labor of online writing center work has become more expansive and immediate, as institutions continue to grapple with how to support their students and staff within remote environments. Central to this call for training is the question of how writing centers cultivate online environments where tutors feel connected and thrive emotionally. Our EI training series is valuable for online educators, online writing centers, and in-person writing centers as it promotes the development of skills central to writing center work—emotional understanding, empathetic communication, and interpersonal relationship-building—while also exploring responses to the emotional labor of this work. We demonstrate how any writing center or educational forum can use EI tools to cultivate a healthy organizational culture online.

Writing Centers, Organizational Culture, and Emotional Intelligence

Writing center scholars have assessed organizational culture through various means but with little focus on how culture comes to be expressed and felt through emotional intelligence. In the writing center community, like many organizations, culture is often passed down through lore, storytelling, and anecdotal accounts that reveal the local context of individual writing centers (Briggs and Woolbright; Nicolas; Harris). Culture also emerges through resistance to narratives, like those that perpetuated norms around standard English, organizational status within an institution, tutors’ pedigree and pedagogy, and student demographics (Harris), giving rise to an understanding of writing center culture as existing within the noisy margins of negotiation and innovation (Boquet; Carino; Fischer and Harris; Heckelman; Pemberton). Institutional context, including physical location and departmental ties, along with center-specific resources, ranging from external-facing mission and vision statements to internal training procedures and reporting tools, have been key intersection points for local expressions of writing center culture (Boquet; Carroll; Griffin et al.; Grimm; Hall; Malenczyk; Nicklay), whereas professional publications, conference proceedings, and listserv conversations call attention to unofficial trends within the professional community (Griffin et al., Grimm; Lunsford and Ede). Additionally, collaborative research supports emergent views of the writing center community through empirical data that unites the local and national cultural context of centers (Babcock and Thonus; Griffin et al.; Valles et al.). Despite this thriving conversation of writing center culture, significant attention has not been paid to how writing centers define their culture and, specifically, how a center’s emotional health or its employees’ individual emotional intelligence impacts the community’s culture. Despite this thriving conversation of writing center culture, significant attention has not been paid to how writing centers define their culture and, specifically, how a center’s emotional health or its employees’ individual emotional intelligence impacts the community’s culture.

The gap, in part, is due to a struggle to define organizational culture and the means through which to understand it. Organizational culture, according to Schein’s definition, lies in the underlying values, assumptions, and beliefs that arise from responses to shared experience of leadership, team members, and new employees. It, however, has been similarly identified as conveyed through organizational rhetoric, including the way organizations use external-facing mission statements and marketing or recruitment information as well as internal-facing training materials and daily institutional communications to influence community members’ feelings and behaviors (Hoffman and Ford; Ihlen and Heath). Organizational rhetoric is a critical piece of organizational culture, but we argue that exclusive reliance on its messaging limits understanding of the work environment it creates and individuals’ ability to navigate the emotional labor associated with exchanges within this space. We likewise acknowledge that organizational storytelling offers an alternative to organizational rhetoric, as community members pass down institutional wisdom and cultural norms specific to an organization through personal anecdotes and accounts (Gabriel). However, we have found that storytelling also must be scrutinized regularly to ensure the underlying values and beliefs speak to the conditions and environment in which individuals emotionally labor (Table 1).

Table 1

A Comparison of the Varied Modes and Effects of Organizational Rhetoric, Storytelling, and Culture

| Concept | Mode | Purpose/Effect |

| Organizational Rhetoric | external (e.g., mission and value statements, marketing and recruiting materials) and internal (e.g., training materials, organizational announcements) communication | influences member behaviors (Hoffman and Ford; Ihlen and Heath); inspires confidence, trust, or integrity in an organization (Eubanks; Brown et al.; Fisher) |

| Organizational Storytelling | personal stories and anecdotes; informal conversation; mentoring | generates consensus and identity formation, encourages problem-solving (Eubanks; Brown et al.); exposes gaps (Condon) |

| Organizational Culture | underlying assumptions; espoused beliefs and values; artifacts (e.g., organizational communications, structures, and processes) | leads to shared community experience, understanding, problem solving, and unified vision (Schein) |

Schein’s definition of organizational culture draws attention to how organizational culture is interlaced with community members’ emotional experiences. Though Schein describes culture as “an abstraction,” he reports that “its behavioral and attitudinal consequences are very concrete” (8). Organizational culture must be examined iteratively, as culture lies in the underlying assumptions, values, and beliefs that arise from responses to shared experiences of leadership, team members, and new employees. Though Schein’s theory of organizational culture relies on individuals’ emotional responses, he emphasizes that these behaviors are equally reflective of groups in which employees participate, particularly as they become reiterative responses to routine interactions. Cultivating or changing an organization’s culture thus starts with understanding ourselves as individuals and as a community. Individuals’ varied emotional responses across team or project work versus one-to-one client interactions can highlight different layers of cultural expressions, just as involvement in a professional organization can cultivate a shared emotional understanding of an individual’s daily work. By taking the time to examine how staff regularly use emotions in response to daily tasks, team interactions, and professional activities throughout writing center work, writing center professionals can gain a more robust understanding of writing center culture and how it stems, in part, from emotional health and wellness. We, in response, demonstrate how discussing these principles of emotional intelligence and organizational health can build upon a center’s culture and connectedness.

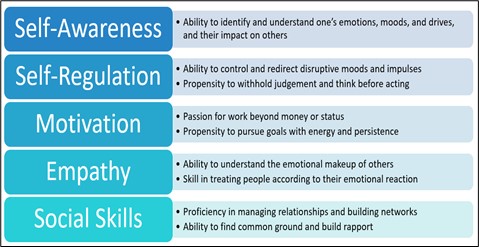

In that regard, emotional intelligence plays a vital role in our ability to understand a center’s cultural makeup and how administrators and tutors can positively impact the health of its culture as it evolves. Emotional intelligence helps members of an organization navigate changes to their environment and community in an emotionally healthy manner (Figure 3). Currently, individual tutoring sessions are the primary site where EI discussions come into play. Tutors must be adept at evaluating and responding to students’ emotional needs and the impact of those needs on writing, while adjusting their own emotional responses to guide and instruct with wellness in mind. Rebecca Jackson et al. similarly recognize the emotional labor administrators endure through the training, development, and mentoring of individual staff. Yet, thinking about EI through the lens of organizational culture enables us to see how emotional health and wellbeing factors into staff’s ability to respond to fluctuations in a center’s development. EI plays an essential role in helping members of a center negotiate variations in staff, tutoring offerings, and daily operations as well as more widespread changes stemming from budget cuts or turnover in institutional leadership. It has been a foundational tool in the response to COVID-19 for educators and administrators looking to understand and mitigate the added emotional labor associated with working remotely. Writing center work does not stop when these cultural and organizational shifts occur; it requires staff and administrators alike to employ EI as a means of responding to them. Investing in EI training will not eliminate the emotional labor associated with these fluctuations within a center, particularly as centers adjust to tutoring in the time of pandemics and administrators face increasing pressure to streamline services on reduced budgets. However, it can better prepare staff to communicate their emotional needs and employ greater self-care when such events do arise.

Resources on EI’s importance and impact during COVID-19 pandemic

- Yale News: Using emotional intelligence to combat COVID-19 anxiety

- Berkeley Greater Good Science Center: How to support teachers’ emotional needs right now

- Johns Hopkins School of Public Health: How to lead in emotional intelligence in the time of COVID-19

Specific to our purpose, we draw attention to the way EI better equips staff to handle the emotional labor unique to online writing center work. We see this use of EI as both a gap in the existing research and a significant need within the writing center community (Jackson et al.; Noreen Lape) as centers increasingly turn to online tutoring to extend and enhance their services. Online tutoring, especially asynchronous tutoring, often heightens the challenge of assessing and responding to students’ emotional needs, as expressions of stress, frustration, excitement, or indifference are harder to detect. Staff must adapt to a tutoring environment where students’ affect and its impact on their writing may be unknown or less apparent. Advancing a team’s emotional intelligence enables a more intentional and concrete articulation of organizational culture to emerge, thereby creating the space to discuss culture’s impact on individual health and a center’s wellness. Tutors likewise may struggle with the daily routine of an online workspace where their own emotional needs may be hidden from immediate view. We have found both in our regular practice and through our training series that the emotional labor of online writing center work extends well beyond individual tutoring sessions. It is also interwoven throughout online project work, team meetings, daily email communications, and ongoing professional development and training opportunities—each of which, in a remote environment, is mediated through technology. Though beyond the scope of our initial training series, we acknowledge how online environments pose additional challenges for members of multicultural, queer, and gendered communities, as they already advocate daily for equal recognition of their identity and unbiased understanding of their emotional needs. While emotional intelligence cannot eliminate emotional labor’s challenges, it is a means by which individuals and team members can attune themselves to recognizing and expressing emotional wellness within safe, inclusive environments.

A healthy writing center is an organization comprised of emotionally intelligent individuals and communicators, but this process ultimately starts with the culture that staff generate and reproduce through their understandings of and reactions to shared experiences. Advancing a team’s emotional intelligence enables a more intentional and concrete articulation of organizational culture to emerge, thereby creating the space to discuss culture’s impact on individual health and a center’s wellness. We, for this reason, designed the following training series as an exploration of how emotional intelligence underwrites our ability to support a healthy staff and generate a healthy organizational culture.

Context for the Training

Our emotional intelligence training emerged, in large part, out of a need to revisit the connectedness of our team after numerous shifts in our organizational structure and culture. The impact of these changes remained unprocessed in terms of our staff’s emotional wellbeing. The Walden Writing Center experienced significant growth in 2015. Our director’s proposal to grow the center and provide salaried positions to create more opportunities for students to access our services was granted, resulting in a doubling of the staff. The writing center is now a robust operation comprised of a director, four associate directors, eight managers, seventeen writing instructors, and seventeen editors. The large staff maintains two primary services: the paper review service and the form and style service and a multitude of additional services, such as webinars, course visits, residencies, doctoral writing assessments, and chat, email, and social media offerings. It was challenging to maintain connection for a large staff with varied roles. Two years after this growth period, our center shifted from a partially to a fully remote team, which further altered our team’s dynamic and communication.

These changes significantly influenced our center’s organizational culture, but it took time to discern the emotional impact on staff’s wellbeing. While our center always worked asynchronously, some employees had to adapt quickly to working as a fully remote team while others never had the opportunity to experience the team’s face-to-face dynamics. All staff now had to overcome the constraints technology places on communication and find new means of connecting with one another, similar to what many experienced in response to COVID-19. This challenge to connection and the lack of sensory input needed to interpret social learning and emotion impacted our organizational culture. More importantly, it called for thoughtful inquiry into what our culture became through this growth and transition to a fully remote experience.

To understand this impact, we had to revisit where emotional labor existed in our work. Walden writing instructors review twenty papers a week and must complete appointments within two days. Our live chat offers instantaneous support, our email service promises a twenty-four-hour response time, and our course visits feature daily responses to student questions. Throughout, staff are expected to be present and attentive to students’ needs, execute quality work that promotes learning, and be knowledgeable of supporting resources—all of which set high standards for responses that require high emotional intelligence. Furthermore, because our support is primarily written communication, there is always a historical record. Public accountability, while motivating, can also create anxiety around the mode of communication. Each of these factors—deadlines, high expectations, and public accountability—involves emotional labor and can create employee fatigue, stress, and feelings of disconnection. While much of this emotional labor was present throughout our work prior to any organizational change, staff had experienced these challenges differently, having been a previously smaller, hybrid team and, therefore, had varied methods for coping. For example, prior to the 2015 expansion, most staff worked in an in-person office setting and, similar to a small start-up team, created several of the services our center now maintains. Staff could easily turn to those around them for support, encouragement, and approval. When the writing center doubled in size, many original staff were promoted, and more remote employees were added. Promoted staff adjusted to newly developed positions within a growing organizational structure, and the team as a whole adapted to communicating and collaborating as a group in various locations. The center was no longer in a start-up period and rather was established and in need of being maintained. Staff experiencing different stages of institutional culture and the center being in a new stage of development strained our team’s shared experience and common understanding.

The expansion of staff and the fully remote transition, in turn, were not merely organizational changes; they marked shifts in our organizational culture. We had to rediscover what connectedness looked like as a larger, fully remote team and found it required additional forms of emotional labor. With miles of physical distance between our staff and technology obscuring individuals’ affect, emotional health easily became overlooked. Connection and authentic communication across a large team and in a remote environment requires vulnerability, intentionality, and risk-taking (Wang et al.), with risk-taking being as simple as speaking up during a recorded meeting or as daring as being forthright in communicating emotional needs. EI became a way to process and understand our center’s organizational changes, but it also built upon common skills needed in writing center work, including emotional understanding, empathetic communication, and interpersonal relationship-building. It became a way to recognize the gaps in our team’s connection and provide staff with the tools needed to navigate emotional wellness across a large team within a remote environment. Our writing instructor team thus launched an EI training series in 2018, as part of broader healthy organization initiative, and with the goal of fostering an emotionally healthy work environment.

Emotional Intelligence Training

Our EI series was a required training for our writing instructor team, which at the start of the training consisted of nineteen writing instructors. The training occurred once a month for the entirety of 2018. Each session was facilitated through Skype and was an hour-long training consisting of lecture, activity, and discussion.

We explored EI themes based on interests beneficial to our team while also incorporating topics from formalized EI trainings, including:

- interpersonal and self-perception,

- interpersonal relationships and empathy,

- adaptability and decision-making,

- general mood and self-expression,

- stress management,

- and emotional understanding and management regarding goal setting (Gilar-Corbi et al.).

Below, we break down each session chronologically. There is also thematic overlap between sessions as our goal was to scaffold trainings where we could expand our understanding of EI across our team and our organization as a way of cultivating a healthy writing center culture.

Training 1: We began our training with an explanation of EI and its benefits to individuals within shared community work environments. We first gauged staff’s understanding and use of EI through a survey before providing an introduction to EI. We then discussed staff’s results on the Meyers Briggs personality tests in order to begin understanding ourselves better.

Training 2: We next reviewed common email scenarios to understand our emotional responses and illustrate EI “[use] in everyday situations” (Hodzic et al. 145). We shared fabricated emails of various tones, syntax, and subject matter with our team, and then discussed individual interpretations of and reactions to each email (Figure 4, Appendix A). This exercise led to a discussion about communication preferences and strengthened awareness of how people might interpret content differently. This training was especially pertinent, as email is vital to our daily communication.

Training 3 and Training 4: We continued to scaffold our ideas as trainings progressed from examining EI’s application to the self and to others. In the first of two trainings, we focused on defining emotional regulation and applying it to ourselves. The following month, we expanded our conversation to discuss differences between intrapersonal and interpersonal emotional regulation and ways to engage perspective-taking (Hofmann et al.).

Training 5: Having considered emotional regulation in connection to ourselves and others, we felt it important to address our goal of feeling connected as a large, remote team. We brainstormed ways our remote team could use EI techniques to create sincere connections, particularly for those seeking deeper, more frequent interactions at work. We examined our use of Yammer and Skype to continue building and practicing EI through additional synchronous and asynchronous interactions with our colleagues.

Training 6: Our sixth training focused on unconscious bias and its impact on our daily work with students and each another. The discussion expanded on EI’s tenets of understanding the self and the importance of perspective-taking. Additionally, the topic of unconscious bias aligned with our center’s diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, as we discussed results from the Harvard bias test via Project Implicit (Figure 5) that participants completed prior to the session.

Training 7: In our seventh training, we discussed the emotional labor of our daily work (Hochschild), including the toll of working remotely. We focused on common scenarios we find challenging (e.g., students who come to us upset or insist on immediate answers to complex questions) and ways to mitigate the effects of emotional labor. This training enabled us to revisit our experience as a remote team and identify the shared values we espouse in response to the emotional labor of writing center work.

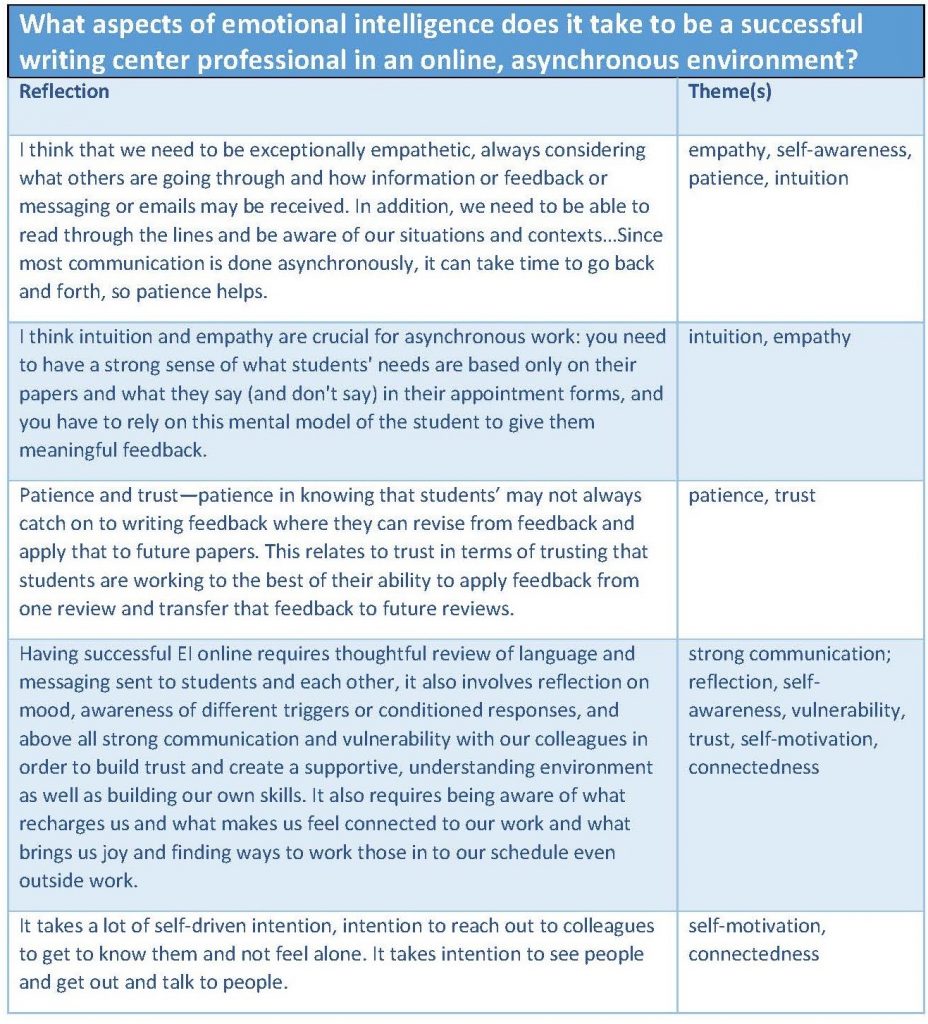

Training 8: In our eighth training, we practiced reflective writing as a way of learning about ourselves, our center, and our roles as writing center professionals (Table 2, Appendix B).

Table 2

Responses to Reflective Writing Prompt and its EI-related Themes

Training 9: For this session, we explored having open conversations around mental and emotional health at work and the benefits to our remote team culture. We discussed ways to share our mental states with others and the added support, connection, and wellness this type of candid communication could create for our team.

Training 10: Our tenth training centered around a chapter of Douglas Stone and Sheila Heen’s book Thanks for the Feedback. We discussed the text’s concepts of baseline response and emotional swing in order to establish how to create stronger emotional balance in response to stimuli (Appendix C). This session involved optional in-depth sharing of personal struggles, experiences, and challenges, which further enhanced a shared understanding of our remote work experience and our connection as a team.

Training 11: Toward the end of our series, we focused trainings on ways EI impacts our center’s vision, goals, and culture. We created personal vision statements to apply what we learned about ourselves through the EI training into specific, achievable actions aligned with our center’s goals and desired team culture.

Training 12: For our final session, we reviewed our year-long training series and completed an EI survey like the one administered at the year’s beginning to gauge progress and change. We wrapped up our training by reflecting on practices we could employ moving forward to continue building EI as individuals and as a team.

Assessment

We wanted to provide staff with meaningful EI training that enhanced our shared understanding of remote writing center work, expanded our team’s connectivity, and fostered a healthy organizational culture. To assess our training’s impact, we issued two surveys at the year’s beginning and end and offered additional feedback opportunities after individual sessions. By gathering feedback throughout the year, we hoped to understand what our colleagues found helpful, measure our training’s impact on individual levels, and provide an outlet for critical considerations in pursuing future training initiatives. We also used feedback to develop and adapt sessions to meet our team’s unique needs.

We issued the first survey in our initial training session. Thirteen out of nineteen staff members who attended the training completed the survey. The survey included a mix of scaled and free-form answer questions. We inquired about instructors’ understanding and use of EI at work, its importance and frequency within online environments, and EI strategies they currently applied in their work. After the training’s completion, we re-issued the same survey to understand if and how instructors’ EI changed over the year and again received thirteen submissions. In the second iteration, we included additional reflective questions asking respondents if the trainings raised their EI level, impacted their EI understanding, and eased use of EI online as well as what aspects of EI were still challenging.

There are several limitations to our training series’ results. One consideration is our survey’s sample size, which included nineteen writing instructors at the year’s beginning but only eighteen at its end. While thirteen participants responded to each survey, we cannot guarantee the same thirteen staff responded to each survey. Regardless, this response rate provided a representative sample of instructors knowledgeable of the training and its impact. We also recognize that email and Skype presentations are important aspects of our daily communication. Our staff value regular discussion of communication within these platforms and this could predispose individuals to evaluate the training favorably. Lastly, our training’s engagement was bolstered by required attendance and our administrative leadership’s investment in additional health initiatives beyond our training series throughout the year. We recognize these results may not be reflective of other writing centers and complicate our ability to apply conclusions widely. We do, however, believe our results provide a baseline for further research and demonstrate success potential for other organizations looking to implement similar training sessions.

Below, we provide an overview of staff’s feedback and its implications on the value of the training series. In the first survey, staff generally defined emotional intelligence as an awareness of one’s own and others’ emotions, and the ability to change behavior and reactions in response to that awareness. When asked to reflect on how they employ EI in their workday and what strategies they use, staff responses can be summarized in these ways:

- empathy in student interactions,

- emotional labor required to understand students and other staff clearly,

- emotional regulation practices,

- reflection before responding to students or co-workers,

- and work to employ vulnerability in interactions.

These responses demonstrate that staff had a sense of what EI entails, which is likely due to the nature of writing center work as a helping profession.

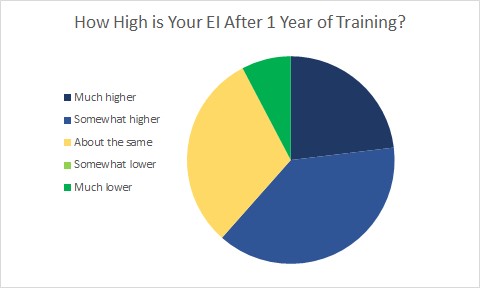

Maintaining and measuring EI effectively, however, are difficult tasks. Therefore, it is unsurprising that responses varied widely in management of EI online. While the majority of participants noted that their EI was higher or much higher than the previous year (Figure 6), there are instances where a respondent considered their EI lower, which could stem from the difficulty of mastering EI as a lasting trait. Negative responses may indicate staff resistance to the trainings, or a disagreement regarding EI’s place in writing center work. However, for the majority of the responses, EI training seemed to create a greater awareness of EI’s depth and complexity, as well as its application to daily writing center work.

Reflecting on our trainings’ impact, staff commented on emotional awareness of self and others but also reported using that awareness to enhance our team’s connectivity, empathetic communication, and interpersonal relations. Staff reflections, which we elicited periodically over the course of our training, included expressions of “connecting on a personal level” to colleagues and a strong sense of teambuilding. Though staff explained that it was difficult to connect with others in an online environment in general, they noted that the training helped them feel able to be vulnerable as well as more comfortable offering “positive feedback and encouragement but also coaching feedback” because all staff had been engaged in EI training throughout the year. Finally, respondents disclosed feelings of self-discovery and connectedness to their work:

I have grown so much in my awareness of myself and my interactions with my colleagues and team online. I have realized that I need to put the work in to make my appreciation and reactions apparent to others while also realizing when I need to take a break or step back and reflect before responding. I feel fuller, more connected to my colleagues.

Respondents acknowledged their emotional and nonverbal reactions had a significant impact on their ability to understand, communicate, and connect with others in a positive manner, demonstrating growth in self-awareness, emotion management, and interpersonal communication. These responses, however, also showed the value of EI training as a team building activity. Staff consistently noted how the training helped them understand their shared work environment and foster connectedness as individuals and as a team.

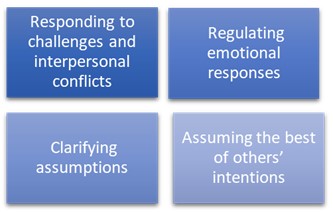

In addition to staff’s self-reported survey results, we asked our administrators to provide their impressions of our training’s impact. One administrator expressed the belief that the trainings positively impacted staff in our online workspace and mitigated some potential negative impacts of online work. Another administrator found that staff showed improvement in “responding to challenges and interpersonal conflicts,” “regulating their emotional responses,” “clarifying assumptions,” and “assuming the best” of others’ intentions (Figure 7). These responses support facets of a strong team culture and healthy organization in addition to demonstrating EI qualities important to writing center work.

Overall, our staff’s and administrators’ responses indicate that these trainings were valuable for cultivating emotional awareness and enhanced connection as a team. Staff noted, as a result of our training, improvements in their reactions to and interactions with others as well as feeling confident in employing greater empathy, openness, and intentionality in our online work environment. Importantly, respondents tied these developments to knowing our entire team engaged in the same conversations about emotional intelligence and health, thereby calling attention to positive growth in our organizational culture. Staff were able to acknowledge the emotional labor common in writing center and remote work, identified experiences and values that united them, and expressed being better equipped with the tools needed to thrive within these environments. These results indicate that our EI trainings were beneficial to staff’s emotional wellbeing and our goal of building a healthy organizational culture.

Conclusions and Future Considerations

Through the year-long training series, the Walden Writing Center staff worked to advance their EI as individuals and as a team working in a remote environment. As leaders of this project, we created regular training content with the goal of fostering a healthy workplace through increased opportunities for EI growth and enhanced team connectedness.

In developing these trainings, we noticed important implications and gaps in the existing research on EI and its application to writing center work. First and foremost, we recognized a need for EI-specific training for writing center staff. EI is intertwined with wellness, as EI addresses healthy ways to manage and respond to the emotional labor of writing center work and is essential to helping tutors find balance amongst their commitment to student development, the emotional strain of challenging sessions, and their own self-care. However, EI remains underutilized in trainings and research within the writing center community. Lape, for example, examined tutor training manuals for ways to cultivate EI in her staff’s daily practice and overall team culture only to find that these guides focused “far more on cognitive than affective skills,” despite EI being “no less important than knowledge of discourse conventions and the writing process” (1-2). This broader characterization of EI training in writing communities was reflected in our team’s practice as well, with our pedagogical and professional development trainings focused on cultivating staff’s writing support and feedback-related skills through peer workshops, shadow reviews, and journal clubs.

Moreover, though we employed regular wellness meetings to discuss mindfulness and other self-care techniques, staff struggled to manage emotions associated with both their daily work and communication within a remote environment. The results of our trainings revealed an increase in staff’s self-awareness of their own EI as well as its application to their work through enhanced adaptability, decision-making, and empathy. Our training series also demonstrated EI’s impact on team connection and provided an outlet for our center to cultivate a healthy online writing center culture where staff can feel confident navigating the challenges of their work and thrive emotionally. We, for this reason, see an opportunity for EI to become an integrated component of writing center training and pedagogy and suggest that there should be additional research about EI’s influence on tutor preparedness and team culture.

We also discovered the vital need for research and training for writing center staff working in online or remote environments.

We also discovered the vital need for research and training for writing center staff working in online or remote environments. According to the most recent report from the Writing Centers Research Project Survey, out of 202 responding centers, 132 reported that they offered online or virtual services. The previous report recorded 114 out of 193 centers offering these services, indicating an increase from 59% to 65% of centers at least partially operating online in a single academic year. These offerings could be higher as centers continue to determine how best to respond to COVID-19. Despite this rise in online writing services, little research has been conducted on effective training for writing center staff working online. Rebecca Martini and Beth Hewett highlight a specific shortage of scholarship, offering practical advice for online tutoring and training rooted in theory.

Our training was supported by research that established EI’s value in the workplace and as a set of learned skills that could be grown over time. Specifically, Sabina Hodzic et al. found that long-term trainings with clear action steps fostered the strongest EI growth for employees. We also recognize the need to expand research into EI’s impact on psychological safety for all members of our diverse community, which was beyond the scope of our initial training series but is a vital need in remote environments. In an attempt to apply this research to our own workplace and address potential gaps, our center elected to continue regular EI trainings throughout 2019.

We conclude that EI trainings are a worthwhile investment in developing and supporting writing center staff, as it helps to manage the stress of work and create a healthy organizational culture. EI training is particularly valuable to online workspaces where it can be difficult to foster a strong team culture. We found that EI training enhanced interpersonal communication and connection and that members of our team felt more thoroughly equipped to handle the emotional labor and remote nature of our writing center work. Moreover, our series enabled us to examine and then demonstrate how EI training benefits those throughout the writing center field, including administrators and staff faced with the challenge of effectively and healthily translating face-to-face writing center services to online environments.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the Walden University Writing Center instructor managers for encouraging us to conduct this year-long training and supporting our pursuit of this chapter, and thank you to the entire writing instructor team for participating in these trainings and engaging in meaningful discussions that strengthened our organizational culture. Additionally, thank you to Nicole Townsend, current director of the Writing Center at Capella University and former writing instructor at Walden, for her work on these trainings and inspiring center interest in this topic. Thank you as well to all the WLN reviewers and Genie Giaimo for supporting our vision and working with us on this chapter. We are thrilled to have our work available for readers.

Works Cited

Babcock, Rebecca Day, and Terese Thonus. Researching the Writing Center: Towards an Evidence-Based Practice. Peter Lang, 2012.

Boquet, Elizabeth. Noise from the Writing Center. Utah State UP, 2002.

Briggs, Lynn C, and Meg Woolbright, editors. Stories from the Center: Connecting Narrative and Theory in the Writing Center. National Council of Teachers of English, 2000.

Brown, John S, et al. Storytelling in Organizations: Why Storytelling Is Transforming 21st Century Organizations and Management. Routledge, 2016.

Carino, Peter. “Reading Our Own Words: Rhetorical Analysis and the Institutional Discourse of Writing Centers,” edited by Paula Gillespie et al., Routledge, 2002, pp. 91-110.

Carroll, Meg. “Identities in Dialogue: Patterns in the Chaos.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 27, no. 1., 2008, p. 43-62. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442284?seq=1

Condon, Frankie. I Hope I Join the Band: Narrative, Affiliation and Antiracist Rhetoric. Utah State UP, 2012.

Conference on College Composition and Communication. A Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for Online Writing Instruction (OWI). CCCC, 2013. https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/resources/positions/owiprinciples.

Degner, Hillary, et. al. “Opening Closed Doors: A Rationale For Creating A Safe Space For Tutors Struggling With Mental Health Concerns of Illnesses.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, 2015. http://www.praxisuwc.com/degner-et-al-131.

Eubanks, Philip. “Poetics and Narrativity: How Texts Tell Stories.” What Writing Does and How It Does It, edited by Charles Bazerman and Paul Prior, Routledge, 2004, pp. 33-56.

Fischer, Katherine, and Muriel Harris. “Fill ‘er Up, Pass the Band-Aids, Center the Margin, and Praise the Lord: Mixing Metaphors in the Writing Lab.” The Politics of Writing Centers, edited by Jane Nelson and Kathy Evertz. Heinemann, 2001, pp. 23-36.

Fisher, Walter R. “Narration as Human Communication Paradigm: The Case of Public Moral Argument.” Readings in Rhetorical Criticism, edited by Carl R.Burgchardt, Strata Publishing, 2005, pp. 240-61.

Gabriel, Yiannis. Storytelling in Organizations: Facts, Fictions and Fantasies. New York: Oxford UP, 2000.

Giaimo, Genie. “WLN Special Issue: Wellness and Self-Care in Writing Center Work, with Dr. Genie N. Giaimo.” Connecting Writing Centers Across Borders, A Blog of WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship. April 25, 2018. https://www.wlnjournal.org/blog/2018/04/cfp-wln-special-issue-wellness/

Gilar-Corbí, Raquel, et al. “Can Emotional Competence Be Taught in Higher Education? A Randomized Experimental Study of an Emotional Intelligence Training Program Using a Multimethodological Approach.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 9, no. 27, 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6030676/.

Goleman, Daniel. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Bloomsbury Publishing, 1995.

Griffin, Jo Ann, et al. “Local Practices, National Consequences: Surveying and (Re)Constructing Writing Center Identities.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, 2006, pp. 3-21. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442246?seq=1

Grimm, Nancy. “New Conceptual Frameworks for Writing Center Work.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 29, no. 2, 2009, pp. 11-27. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43460755?seq=1

Hall, R. Mark. “Theory In/To Practice: Using Dialogic Reflection to Develop a Writing Center Community of Practice.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 31, no. 1, 2011, pp. 82-105.

Harris, Muriel. “Making Our Institutional Discourse Sticky: Suggestions for Effective Rhetoric.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 30, no. 2, 2010, pp. 47-71. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442344?seq=1

Heckelman, Ronald. “The Writing Center as Managerial Site.” The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 23, no. 1, 1998, pp. 1-4. https://wlnjournal.org/archives/v23/23.1.pdf

Hewett, Beth L. The Online Writing Conference: A Guide for Teachers and Tutors. Bedford/St Martin’s, 2015.

Hewett, Beth L, and Rebecca H. Martini. “Educating Online Writing Instructors Using the Jungian Personality Types.” Computers and Composition, vol. 47, 2018, pp. 34-58. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S8755461517300531

Hochschild, Arlie R. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: U of California P, 1983.

Hodzic, Sabina, et al. “How Efficient Are Emotional Intelligence Trainings: A Meta-Analysis.” Emotion Review, vol. 10, no. 2, 2017, pp. 138-48. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1754073917708613

Hoffman, Mary, and Debra Ford. Organizational Rhetoric: Situations and Strategies. SAGE Publications, 2010.

Hofmann, Stefan G., et al. “Interpersonal Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ierq): Scale Development and Psychometric Characteristics.” Cognitive Therapy and Research. vol. 40, no. 3, 2016, pp. 341-56.

Ihlen, Øyvind, and Robert L. Heath. The Handbook of Organizational Rhetoric and Communication. Wiley Blackwell, 2018.

Jackson, Rebecca, et al. “Writing Center Administration and/as Emotional Labor.” Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, http://compositionforum.com/issue/34/writing-center.php.

Lape, Noreen. “Training Tutors in Emotional Intelligence: Toward a Pedagogy of Empathy.” Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 33, no. 2, 2008, pp. 1-6. https://wlnjournal.org/archives/v33/33.2.pdf

Lunsford, Andrea, and Lisa Ede. “Reflections on Contemporary Currents in Writing Center Work.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 31, no. 1, 2011, pp. 11-24. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442355?seq=1

Mack, Elizabeth, and Katie Hupp. “Mindfulness in the Writing Center: A Total Encounter.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 14, no. 2, 2017. http://www.praxisuwc.com/mack-and-hupp-142.

Malenczyk, Rita. “’I Thought I’d Put That in to Amuse You’: Tutor Reports as Organizational Narrative.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 33, no. 1, 2013, pp.74-95. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442404?seq=1

Martini, Rebecca H., and Beth L. Hewett. “Teaching Tutors Not to Tutor Themselves: Personality in Online Writing Sessions,” ROLE: Research in Online Literacy Education, vol. 1, no. 1, 2018. http://www.roleolor.org/martini–hewett-personality-in-online-writing-sessions.html.

Nicklay, Jennifer. “Got Guilt? Consultant Guilt in the Writing Center Community.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 32, no. 1, 2012, pp.14-27. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442378?seq=1

Nicolas, Melissa. “Why there is no ‘Happily Ever After’: A Look at the Stories and Images That Sustain Us.” Marginal words, marginal work?: Tutoring the Academy in the Work of Writing Centers, edited by William J. Macauley and Nicholas Mauriello, Hampton Press, 2007, pp. 1-17.

Pemberton, Michael. “The Prison, the Hospital, and the Madhouse: Redefining Metaphors for the Writing Center.” Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 17, no. 1, 1992, pp. 11-16.

Schein, Edgar. Organizational Culture and Leadership. Jossey-Bass, 2017.

Stone, Douglas, and Sheila Heen. Thanks for the Feedback. Penguin Books, 2014.

Valles, Sarah Banschbach, et al. “Writing Center Administrators and Diversity: A Survey.” The Peer Review, vol. 1, no. 1, 2017, http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-1/writing-center-administrators-and-diversity-a-survey/.

Wang, Yanfei, et al. “Humble Leadership, Psychological Safety, Knowledge Sharing, and Follower Creativity: A Cross-Level Investigation.” Frontiers in Psychology, Frontiers Media S.A., 19, 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6156152/.

Writing Center Research Project Survey. Purdue Online Writing Lab, 2014. https://owl.purdue.edu/research/writing_centers_research_project_survey.html.

Appendix A

Main Focus: Emotional Intelligence and Email Communication

Context: As an online center, email is a primary form of communication we deal with daily but can be sources of added anxiety, stress, confusion, and emotional labor. This exercise was designed to create the space for staff to discuss their emotional response to various communication styles and identify their own preferences for expressions. This exercise could easily be adapted to role-playing communication from students or between staff members in an in-person environment as well.

Length: 1 hour

Presentation: To begin, introduce common complaints associated with email communications. We used examples from Shirley Taylor’s Email Etiquette: A Fresh Look at Dealing Effectively with Email, Developing Great Style, and Writing Clear, Concise Messages, including:

- Vague subject line and/or message

- No greeting and/or no sign off

- Sloppiness (e.g., treating email like text messages)

- Tone (e.g., unfriendly, directive, chatty)

- Being forced to hunt for a response

- Incorrect usage of capital letters (e.g., using ALL CAPS to express emotion or emphasis)

Activity A: Then, create a check-in where staff discuss their own habits, emotional reactions, and preferences when sending and receiving emails.

Questions might include:

- Do I differentiate my tone/style depending on the individual or group I am sending the email to?

- What are my own pet-peeves concerning email?

- Have I met this individual sending the email in person? Does knowing/not knowing this individual affect how I read this email?

- Are there any emails I disregard without reading? If yes, what signals me to disregard specific emails?

- How do I determine whether or not I should respond?

Activity B: Next, share fictional emails (or scenarios) with the staff. After reviewing each email, use the questions listed below to reflect on staffs’ emotional response to each email and what next steps they might take.

Directive Email:

Hello, William,

This is a reminder to keep track of your work and hours carefully and ensure you are presenting your best self to students. As you know, students are very important to us.

Be sure to:

- Review your introduction and conclusion in paper reviews to ensure a conversational tone.

- Read back through emails to students before you send them, making sure that you address their concerns.

- Track your time in TMI as Papers or Student Communication.

- Prioritize papers using the priorities checklist.

Melanie Atwood, PhD

Director of Writing Things

Walden University

Nondirective email:

Hi, Glinda,

Good morning! I was hoping to dive into our slide revisions for our upcoming presentation. I have different thoughts on where we might begin. First, there is some information on slides 4, 6, and 7 that is out of date. I was hoping that someone could update these details. Second, I was concerned about the amount and density of instructional content throughout the presentation. I know that we have a lot of ground to cover, and it all seems like essential information to address. We don’t usually make it through the entire slide deck. Perhaps we could build in more discussion questions to break up the instructional content. Thirdly, I had this idea that we could incorporate some of the recent update on APA formatting to share with everyone. Is there a place where you think we could fit this information and resources in? We probably need to get started on these revisions soon since the presentation is next week.

Oh, and, before I forget, we also need to address the post-presentation survey. I recall that some participants had trouble accessing it. The main issue is that it is missing the updated questions from quality metrics.

I am interested in hearing your thoughts. Thanks for all of your hard work!

Sincerely,

Jamie

Discussion Questions:

- What was your initial reaction to this email?

- What is your image of the individual behind this email?

- What do you like about this email?

- What do you dislike about this email?

- Does this email invite a response?

- What would your next step be after receiving an email like this?

Wrap up Presentation: Finally, provide some possible tips to crafting and responding to email communication, including discussion of:

- Opening address

- Purpose for email (e.g., “I’m reaching out because…”)

- Not assuming; giving the sender the benefit of the doubt

- Invite response, start dialogue (e.g., “If you have any questions…”)

- Sincere sign-off

Source:

Taylor, Shirley. Email Etiquette: A Fresh Look at Dealing Effectively with Email, Developing Great Style, and Writing Clear, Concise Messages, ebook, Marshall Cavendish International, 2010.

Appendix B

Main Focus: Reflective Writing and Emotional Intelligence

Context: The goal of this session was, first, to consider connection between mindfulness, emotional intelligence, and reflective writing, and, second, to create the space for staff to explore this relationship through a series of rapid reflections. This session was completed at the mid-point in our year-long training series and included a review of key concepts from previous EI trainings in the year. Through this presentation, review, and reflection activity, we aimed to take a closer look at our team’s culture and identity as well as to build a healthy organization.

Length: 1 Hour

Presentation: To start, provide a quick overview of what mindfulness entails and how it both relates and differs from emotional intelligence. Below are a few principles we reviewed:

- Mindfulness

- Inward focus on an individual’s thoughts and feelings without fear of judgment (Goleman and Lippincott)

- Act of noticing (i.e., by noticing emotions, anxieties, ideas, stressors, you can strengthen neural pathways and create a calm, confident headspace)

- Emotional Intelligence

- Comprised of the perception, understanding, and management of emotion in the self and in others (Kirk et al.)

- Attention to behavior patterns and emotional labor

- Learn how to respond rather than react

- Establishes a foundation to build competencies, realistic expectations or goals, and wellness practices

Once you have reviewed these concepts, identify how reflective writing can help bring greater awareness to each of these concepts. Below are a few principles we discussed:

- Reflective writing: the act of writing about meaningful emotional experiences

- Benefits include:

- Enhances cognitive processing and restructuring

- Helps articulate or visualize thoughts and emotions

- Enables individual to recognize patterns

- Can lessen stress and anxiety around events or habits

Activity: Next, create the space for staff to engage reflective writing. To do so, have staff type anonymously or write and share responses to the following prompts. After each written reflection, take a few minutes to share what staff learned. For more details, see the list of supporting questions below each reflection prompt.

**Note: We focused our reflection questions on aspects of the staffs’ own sense of purpose and connection and explored how this individual emotional connection translated to our center’s overall culture, remote environment, and the larger writing center community. However, these prompts could easily be adapted to focus on other areas of EI, emotional labor, mental health and wellbeing, team culture and dynamics, or general staff experiences.**

Reflection Prompt 1: Take 5 minutes to read and respond to questions 1 and 2.

- How would you describe your purpose as a writing center professional?

- How connected do you feel to this purpose on a daily basis? What challenges do you face that might impede or make it difficult to achieve this purpose?

Afterward, share responses and reactions as a group. Participants might share:

- What you learned about yourself

- What you learned about others’ sense of purpose

- If you noticed common themes in the connection we feel or challenges we face in writing center work

Reflection Prompt 2: Take 5 minutes to read and respond to questions 3 and 4.

- How would you describe our culture as a writing center? What would you say are the core values of our center?

- What aspects of emotional intelligence does it take to be a successful writing center professional in an online, asynchronous environment?

Afterward, share responses and reactions as a group. Participants might share:

- What you learned about our center (e.g., culture, core values)

- What is shared about how we understand online writing center work

- Whether there were common themes in the responses

Reflection Prompt 3: Take 5 minutes to read and respond to questions 5 and 6.

- What core principles do we share with other writing centers?

- What advice might you share with the larger writing center community about how to maintain positive self-care and wellness as both a writing center professional and one that works within an online, asynchronous environment?

Afterward, share responses and reactions as a group. Participants might share:

- What you learned about our view the larger writing center community

- What we share or unites us as writing center professionals

- Whether there were common themes in the advice we’d share about our work

Sources:

Goleman, Daniel, and Matthew Lippincott. “Without Emotional Intelligence, Mindfulness Doesn’t Work.” Harvard Business Review, 8 September 2017, https://hbr.org/2017/09/sgc-what-really-makes-mindfulness-work, Accessed 14 August 2018.

Kirk, Beverly, et al. “The Effect of an Expressive‐Writing Intervention for Employees on Emotional Self‐Efficacy, Emotional Intelligence, Affect, and Workplace Incivility.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology, vol. 41, no. 1, 2011, pp. 179-195.

Appendix C

Main Focus: This training was composed of two parts: 1. “swing and baseline” and 2. “sharing and mental health.”

Part I

Context: In Part I, we discussed terms and concepts from Stone and Heen’s book, Thanks for the Feedback.

Length: 30 minutes

Presentation: To begin, use Stone and Heen’s book, Thanks for the Feedback, to introduce and discuss the terms swing, baseline, sustain, and recovery. Below is a quick overview of each term. Once you have defined each term, provide an explanation of the four sustain/recovery combinations.

- Baseline “refers to the default state of well-being or contentment toward which you gravitate in the wake of good or bad events in your life” (150)

- Swing “refers to how far up or down you move from your baseline when you receive feedback” (150).

- Sustain and recovery “refers to duration, how long your ups and downs last” (150)

- Four sustain/recovery combinations: Quick recovery from negative, long sustain of positive; Quick recovery from negative, short sustain of positive; Slow recovery from negative, long sustain of positive; Slow recovery from negative, short sustain from positive (157-158).

| Long sustain of Pos. | Short sustain of Pos. | |

| Quick Recovery from Neg. | “I love feedback!”

It’s easy to stay positive |

No big deal either way

Positivity is great but I prefer to feel “even keel” overall

|

| Slow Recovery from Neg. | “I’m hopeful but fearful”

When something bad happens I feel down for a while

|

“I hate feedback”

I try to stay positive but bad things always seem to happen

|

Activity A: Using a variety of situations, have participants identify where they would land on the swing spectrum using the four sustain/recovery combinations provided above, which can also be found on pages 157 – 158 of Stone and Heen’s book. Some examples we used during our session included:

- If a student expresses extreme frustration to you in chat about past instructor feedback;

- if you received a thankful email from a student after a paper review appointment;

- if your car breaks down and will be expensive to repair;

- if you have—then resolve—a fight with your partner.

** Note: We used possible examples from both professional and personal settings in order to acknowledge the emotional labor associated with daily work life balance and the impact each has on the other. If preferred, you could adapt these examples to be explicitly writing center or tutoring specific scenarios.**

Participants can then share their responses (optional) and/or a reflection on things that bring them long positive or long negative impacts.

Wrap up presentation: Next, provide an explanation of why knowing swing and baseline is important in the context of EI. Concepts from Thanks for the Feedback we used for discussion:

- 50 percent of our happiness is how we “interpret and respond to what happens to us” and about 10 percent “is driven by our circumstances” (158).

- Understanding swing helps us receive feedback more effectively.

- Understanding swing helps us identify distortions in our own perceptions of ourselves and others’ views of us.

All of these concepts help with EI because they deal with emotional regulation, coping, effective communication, and asking for support from others.

Source: Stone, Douglas, and Sheila Heen. Thanks for the Feedback. Penguin Books, 2014.

Part II

Context: For Part II, we looked to build on the above conversations about swing, baseline, and recovery in order to address the potential impact on staff’s mental and emotional health. While not required, we encouraged staff to be vulnerable about their mental health and did so by first sharing examples of our own struggles. This section of the session was optional, and some staff chose to remain silent and write responses or reflect independently. This session approach may be most successful after some foundational sharing and EI building practice, as our team had worked to establish trust in previous trainings prior to this session.

Length: 30 minutes; 10 minutes for each activity

Activity A: Have staff complete an anonymous poll about mental health challenges with questions like: Have you experienced any of the following: depression, loneliness or isolation, chronic pain, etc.? [Optional, depending on participants’ comfort and team connection: share the number of respondents per each question in order to bring light to what mental health might look like in your center.]

Activity B: Discuss awareness as the first step to creating an active plan to boost mental health. Brainstorm with the group ways to boost mental health through connectivity at work as well as through individual practices at home. These might include: keeping a gratitude journal, taking time to chat with a colleague during the day, sending an appreciative message to a coworker, or meditation.

Then, practice this support of mental health by having staff share something they appreciate about another staff member (verbally or via written message).

Activity C: Once appreciation moments have been shared, offer the following prompted discussion. Allow staff to remain silent if they choose. Have presenters start things off to help begin the conversation:

- What’s something that’s been difficult for you to manage emotionally this year?

- What’s something you feel you handled well emotionally this month?

- Is there anything happening with you now/recently that you’d like to share?

"OWI Principle 7: Writing Program Administrators (WPAs) for OWI programs and their online writing teachers should receive appropriate OWI-focused training, professional development, and assessment for evaluation and promotion purposes."

C's Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for Online Writing Instruction (OWI)