4 The Hidden and Invisible: Vulnerability in Writing Center Work by Lauren Brentnell, Elise Dixon, & Rachel Robinson

Keywords: Vulnerability, emotion, social justice, trauma, identity, embodiment

It’s often uncomfortable to be vulnerable with others, especially within public spaces.

Introduction

It’s often uncomfortable to be vulnerable with others, especially within public spaces. Witnessing others’ vulnerabilities and being vulnerable ourselves asks us to extend empathy that might make us feel uncomfortable. Further, vulnerability is a privilege not always extended to everyone. As white people, we acknowledge that vulnerability doesn’t look the same for everyone and may even be dangerous for certain populations, such as people of color and members of the LGBTQ+ community. Throughout this piece, we consider what Richard Marback means when he says, “vulnerability requires more of us than empathy” (7), and what working with empathetic vulnerability might require of us in the writing center. What does it mean for us, and for more inherently vulnerable populations, to push past empathy into a space of authentic vulnerability? Does this look different in writing centers? As white people, we acknowledge that vulnerability doesn’t look the same for everyone and may even be dangerous for certain populations, such as people of color and members of the LGBTQ+ community. Writing centers are often idealized as successful and happy academic spaces (Grimm; McKinney), which contributes to the promulgation of a welcoming facade. However, writing center scholars often know that the concept of welcome is much more complicated and freighted with the emotional labor of consultants and directors (Caswell et al.; Dixon & Robinson).

When the three of us came together to write about being vulnerable in writing center work, we didn’t realize how we each independently approached the writing center space as one that simultaneously welcomes and rejects visible acts of vulnerability, particularly when enacted by tutors, administrators, and staff members. To be clear, writing centers are often described as “caring” spaces that resist traditional impersonal hierarchical structures and welcome vulnerability, but they also tend to be described as academic spaces that prioritize professionalism. Thus, vulnerability should be present in our interactions with clients but also shouldn’t, because we’re professionals. However, painful moments that require—or demand—visible vulnerability are often unpredictable; people do not schedule writing center appointments around these moments. Instead, moments of vulnerability present themselves in the “everyday” of the center: in our conversations, in our sessions, and in the ways we interact with the writing center space itself, and they are, sometimes, not pleasant or “welcome.”

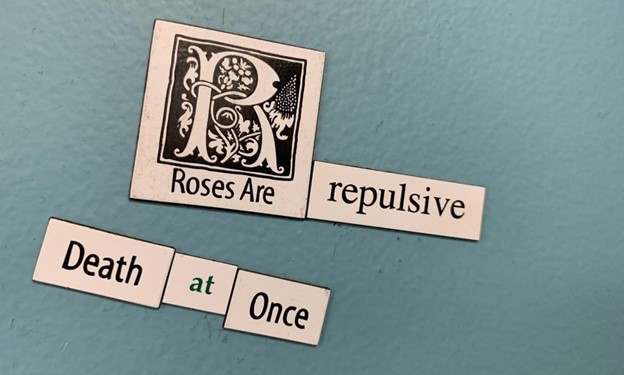

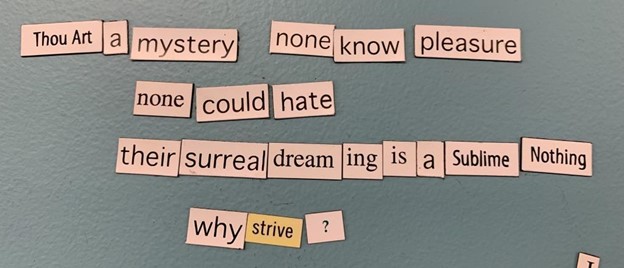

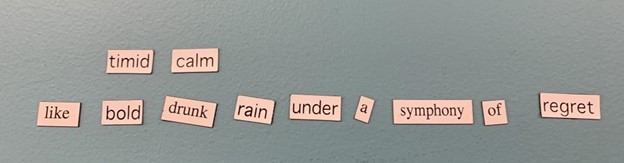

Traditionally, writing centers are marked as comforting spaces, often with touches of “home” like plants, coffee makers, and couches (McKinney). These comforting touches of home (hopefully) help to make the writing center an open, welcoming hangout space for consultants and writers alike. In this space, ordinary moments take place through social interactions but also in the mundane interactions with objects in the center. Gellar et al. call for writing center directors and scholars to “remain open to everyday moments” in the center (56), suggesting readers consider the everyday chats between consultants during their breaks and the meaning made in created and found objects such as magnetic poetry (Figure 1), internet bookmarks, and unshelved books (56). Indeed, they argue that seeing the everyday in these artifacts is one way to uncover what means and what matters in our writing centers” (58).

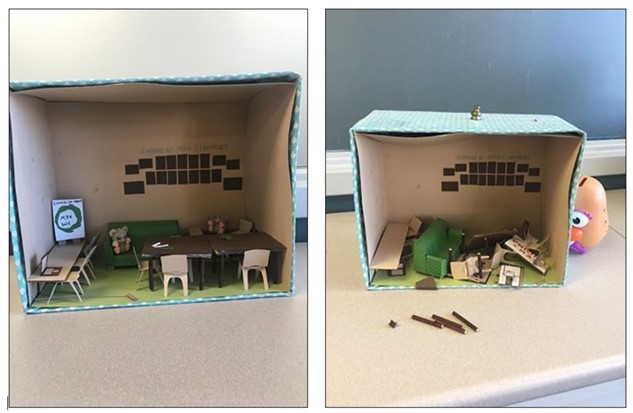

For us, evidence of vulnerability is present in the objects left behind in the center: in neglected plants left to die on the tables (Figure 2), in the magnetic poetry constructed to describe a client or consultant’s grief or apathy, in the toys and crayons broken and pulled apart after an anxiety-riddled session. Photographs of such evidence of everyday vulnerability are scattered throughout this article and are intended to illuminate how inanimate objects can reveal deep—and sometimes negative—feelings.

Because we—and many of those we work with—have painful, difficult moments on a daily basis, we argue for the importance of discussing, exposing, and integrating vulnerability into our everyday writing center work, even as we know this practice is more difficult for some populations than others.

Marback argues that while we often see vulnerability as something to be hidden or overcome, we should instead reorient to seeing vulnerability “not as a weakness but as a strength, an attitude of care and concern that connects us to the world and to each other” (1). This approach sees vulnerability not as something to be hidden away in order to create a “positive” community space, and not, even, as something everyone gets to choose. Instead, it is something to be safely discussed, even when it is uncomfortable. Vulnerability can help to create a community more attuned to all bodies within it, which is (supposedly) at the core of writing center work. In exposing, discussing, and exploring vulnerabilities, we can begin developing social justice-oriented practices in a writing center.

Throughout this chapter, we interrogate what it means to be vulnerable consultants in the writing center. Vulnerability can feel like a loss of control, an irrational response that makes us ashamed, particularly in the academic spaces where we work and rely heavily on rationality as a guiding principle. Instead, we see vulnerability as “emotional involvement,” which “demands from us an acceptance of greater risk than is demanded by empathy” (Marback 7). While empathy is frequently integrated into our work as writing center consultants, vulnerability demands more. We’re often empathetic to those who come to us for help—we take time to understand their writing, why they are writing, the struggles they are having. But vulnerability asks us to also be forward about our own struggles, which can leave us feeling exposed and uncomfortable in interactions with co-workers and in sessions. We are not calling for everyone to always be vulnerable. Instead, we advocate for allowing space for vulnerabilities not to be seen as shameful when they do come forward at work.

This chapter is presented in three parts. First, Lauren, a former consultant at The Writing Center @ MSU (Michigan State University), discusses the need for care-based responses within the writing center to both spoken and silent vulnerability. Then Elise, former interim assistant director at The Writing Center @ MSU and current writing center director at University of North Carolina at Pembroke, presents photos she took of objects in MSU’s center that mark consultants’ and writers’ unspoken vulnerabilities. These photos are peppered throughout the chapter to give a sense of the vulnerabilities that people (including ourselves) express within the writing center in non-verbal ways. Next, we have Rachel’s stories. Rachel, former interim assistant director and current graduate coordinator at The Writing Center @ MSU, writes of having to publicly and vulnerably live through her grief while continuing with the important, everyday tasks of writing center work (Figure 3). Finally, we conclude with strategies for creating and discussing vulnerable moments in your own center.

In Lauren’s research with trauma survivors, she advocates for care-based practices in all areas of our work, including research, teaching, writing program administration, and, of course, writing centers. Care-based practices include:

- Prioritizing the building of safe and open communities (Craig and Perryman-Clark; Herman; Yergeau)

- Promoting empathetic listening (Dolmage; Laub)

- Reflecting on positionality and relationality (Cedillo; Craig and Perryman-Clark; Powell et al.)

- Sharing power and flattening hierarchical governance (Guarino et al.; Tuhiwai Smith)

- Rebuilding networks of trust and care through care-based practices (Herman; Morales)

What we’ve learned from this model of care-based practices is that vulnerability is an active practice, one that we have to train both speakers and listeners to handle. Experiencing vulnerability is scary precisely because it is seen as weakness. We often hide our shame, our worry, our anger, our depression, and our grief from others because we fear the risks associated with being open. Likewise, we often fear being taken advantage of, being shunned, or being viewed as “difficult.” Many of us may not have a choice in that vulnerability; certain positionalities including race, sexuality, ability, class, and nationality are inherently more vulnerable than others, so these experiences and feelings may be heightened.

For listeners, vulnerability is scary because we don’t always know how to handle someone else’s pain, particularly when we aren’t trained as counselors. Even empathetic listeners can mess up by responding in seemingly dismissive ways that make vulnerable speakers feel unheard and unimportant. Therefore, engaging in the work of vulnerability means working to understand how we can make safe and open communities for both speakers and listeners to work together, trust each other, and care for everyone.

This leads us to a series of questions:

- Why is vulnerability in writing centers important—what benefits are there to being vulnerable and acknowledging others’ vulnerabilities?

- Where are these moments of vulnerability in writing center work?

- When do we share our vulnerabilities, and when do we hide our vulnerabilities?

- What is the difference between vulnerabilities that we feel as the result of life experiences and vulnerabilities that are part of our embodied identities?

- How do we navigate vulnerabilities with both empathy and action?

- What does it mean to be “vulnerable,” and does it look the same for everyone?

As part of responding to these questions, we take time to share our own vulnerabilities. While we reflect on these stories of vulnerability, we also relay ideas for how vulnerability can be integrated into writing center work, and how we can better respond to vulnerabilities as listeners, consultants, and co-workers. We hope to start a conversation on the vulnerabilities that we take into the writing center, as well as the vulnerability that the writing center as a space and practice puts on us. We conclude our chapter by providing activities for and examples of modeling vulnerability in your own writing center.

Lauren’s Story

Because it is mid-February in Michigan, I leave my apartment earlier than usual to make sure I have time to clear the snow off my car, navigate the half-cleared Michigan roads, and battle for a parking spot on campus before the lots are filled (a feat even more impossible in the cold, with more students driving rather than walking in the frigid temperatures and some spots taken up by the snow piles). Today, I am lucky and find a parking spot immediately, so I have time to grab coffee and arrive at my shift early. To pass the time before my appointments arrive, I log onto social media.

The first post I see notifies me that a friend of mine has died.

Immediately, I text a mutual friend to confirm the details. We quickly share stories and memories of our deceased friend and our frustration that we must mourn our friends before we are 30. Frustratingly, this is not the first time either of us has had to deal with death during the year—with the death of people our own age, other millennials who we probably just saw on Instagram or Snapchat the day before. Then, my appointment walks in, and I start a 4-hour writing center shift, where I have to shove aside my feelings and work with the writers who had scheduled appointments with me.

After my shift, I don’t get to fall apart—I’m on the job market, and I have an interview planned for the afternoon. So, I stay in the writing center, hoping the relatively public space will help me keep myself together until after I have to answer interview questions about my teaching and research and service—all of which, funnily enough, deal with issues of trauma and care and vulnerability. I’d love to be able to actually enact my research practices with the search committees, to be able to share the details of my life with them, to answer their call with “I just found out my friend died unexpectedly, and this is exactly why I do the work I do” instead of with a “hello,” but I know that doing so would probably mean that I don’t actually get that job. After my interview, I finally message some people in my program to say that my friend died and that I’ve been holding those emotions back all day.

Once I allow myself to feel these emotions, I think about the writing center as a space where I’d been forced to hide those feelings, to perform invincibility, to put on the mask and pretend nothing was going on for the writers who came in for help. Because I was trying to make sure I was caring for the writers I was working with, the mask of professionalism I wore meant that I was failing to care for myself and my emotions. In this way, the writing center felt like a space where I wasn’t allowed to be myself or to feel my own feelings.

But I then consider why I lingered in that space for an hour after my shift instead of going home, and I wonder if it is more complex than that. While I did not speak my vulnerabilities aloud, the writing center was still the space where I felt safe and comfortable in that moment, where I wanted to be in order to remain calm before an interview—it was a space of vulnerability, even if it was a silent vulnerability. The forced professionalism of the writing center, which felt stifling at first, ended up becoming a comfort to me as my shift ended. Because I knew I had to maintain my composure for the interview coming up, I found myself drawing on the writing center as a way to dwell in my emotions without being overwhelmed by them. I confessed what I was going through to a few other consultants who were there at the time, and who asked me how I was doing. They, in turn, offered their sympathies and support in ways that I needed. While I was silent about my feelings while working with writers, in the moment where I was no longer asked to act as a consultant (when my shift was over), I was able to start speaking my vulnerabilities.

Much of my work deals with silent vulnerabilities. Sometimes, this means considering how we can come to speak vulnerabilities and how we speak and story trauma, which carries many vulnerabilities. More recently, and for this project, I have become interested in how we as writing researchers, teachers, administrators, or consultants can support those who are vulnerable, whether we are aware of these vulnerabilities or not. In other words, the writing center may be a space for emotional vulnerability, a healing space as well as a consultation space. I’ve often found myself in the position of being a healer for writers who see themselves as “bad writers” or who don’t believe they can complete an assignment, but rarely have I felt that the center was a healing space for me. Indeed, the writing center seems set up to be a healing space for writers rather than tutors, as we often discuss how to navigate the feelings of those writers. What Elise, Rachel, and I consider here is how it can also be a potential healing space for those of us who work here.

To be clear, sometimes the writing center feels like another abuser, one that asks me to hang my vulnerabilities away at the door in order to work, invalidates my fears and worries, asks me to be professional and sees emotions as hindering that. In this way, writing centers mirror the institutions they are part of, the university settings wherein we are often asked to be students, faculty, and other professionals before we are asked to be people. But I believe that we do not need/have to feel this way in the center. This possibility can only be recognized as we open space for vulnerabilities, to not ask people to hang them at the door, to empathize with each other but also train our consultants to take action to help those who are vulnerable.

In my experience, writing center staff/administrators often pretend we’re not on fire. We put up images of “happy” writers and consultants on our webpages and tout our successes, but we ignore the failures that are all around us, including everyday feelings of depression, anxiety, and loss, or the general feeling of just being overwhelmed that many of us experience at some point (Figure 4).

But exposing vulnerabilities actually makes us a safer, and more honest, community. The writing center does not need to be a space that makes everyone “happy.” In trauma studies, we teach that rebuilding trust is often the exact opposite of making things “happy”: because trauma survivors know that happiness is often a façade, regaining trust is rooted in being open and honest about both personal vulnerabilities and institutional failings (Herman; Smith and Freyd). I believe that the writing center (like many other institutional offices) has often failed survivors in its reticence to address trauma within its walls. Michigan State is in a particularly vulnerable moment in the wake of Larry Nassar, so the reluctance of any space to recognize sexual violence is an issue for all departments to consider. We cannot skip reflecting on our failures, to expose our own vulnerabilities instead of hiding or defending them. We don’t need to just put the “happy writer” stories on the writing center websites—we also need to put the things that show the bad, from the mundane struggles that writers may go through the recognition that writing centers exist within institutional settings that are often filled with harassment, discrimination, and violence.

Tell people how to address discrimination and make space for them to do so, because these stories emerge within the writing center spaces. Provide anti-harassment and intervention training to consultants as part of job training, because many of us who work here and the writers that we work with will experience these at some point. Acknowledge that a large amount of violence occurs within the universities most of us work for and work to address that problem within the writing center, providing university and community-focused resources for both ourselves and the writers who come to us with these stories to utilize.

Elise’s Story

Since 2007, I’ve worked in four different writing centers as a consultant, coordinator, and now interim assistant director. My experiences in each one have been different, but one constant has always remained: they have always been a place where messy things happen. Since writing centers often become a kind of hub for consultants to hang out, the writing center has served as a backdrop and setting for many everyday life moments for me. And I’m a grad student, which means I’ve seen some shit . Thus, writing centers have been a backdrop not just for my happy life moments, but also some of my darkest times. In undergrad, I used my job in the writing center as an excuse to avoid my abusive boyfriend. I’ve also been sexually harassed at two different writing centers, by both a man and a woman. I had a miscarriage in 2017, and the center was a setting for many conversations about my grief. I’ve had arguments. I’ve cried . I’ve hidden. I’ve experienced trauma in the writing center. It’s these everyday moments I want to discuss here.

Arguably, Geller et al.’s (2007) discussion of everyday moments hearkens to the positives of the center, to the way we all like to think of our centers: hubs of fun chit-chat, snack-eating, stimulating consultations, hilarious haikus composed in magnetic poetry, delicious treats left out for all. Of course, most, if not all, writing centers have these moments. But they also have other kinds of moments: moments where consultants and writers disagree or end sessions early; moments where a consultant quietly puts together an angsty poem on the magnet board (Figure 5); moments where no one remembers to water the plants (Figure 6), clean out the coffee pot, or throw away the dried-up markers; moments where our pain and vulnerability are only made visible through the traces we leave behind (Figure 7).

If the writing center is to be conceived of as a homey space, I think it’s only natural for us to think about the “dark” things that happen in home spaces: sexual harassment, death, abuse, tears.

When you have a miscarriage, you’re confronted with a lot of positive narratives about trying again, having a rainbow baby, or the notion that your baby is safe in heaven. None of these narratives brought me comfort or solace. Instead, I found the push for constant positivity to be hollow and stifling. In addition, after my miscarriage, I lived through the interminable wait for Michigan State’s Office of Institutional Equity to make a decision about a sexual harassment case (the setting of which was the writing center) that I filed. We often discuss the positivity to be found in an end result of a case like this, but what of all the negative feelings accompanying the weight (and wait) of it all? Where does that leave me or anyone else experiencing negative feelings in a writing center space often advertised as comforting and happy?

I find myself often seeking comfort under the blanket of bad feelings I have been so often encouraged to recover from or get over. Instead, I have found myself deep-diving into darkness as pure resistance against all the hope-filled narratives of rainbow babies, second chances, and babies in heaven. Last year, in solidarity with queer scholars like Lee Edelman, Ann Cvetkovich, Jack Halberstam, and Heather Love, I found myself holding on to my failure, my depression, my empty womb, my childless future, my traumatized body and spirit. Love argues that “‘feeling bad’ has been a crucial element of modern queer experience” (160) “given the scene of destruction at our backs” (162). Queerly reaching out into the writing center space, I looked (and continue to look) for evidence of some kind of solidarity in my own personal darkness. I have found that a reveling in the negative has often been my only queer comfort. Indeed, according to Cvetkovich, “it might. . . be important to let depression linger, to explore the feeling of remaining or resting sadness without insisting that it be transformed or reconceived” (14). Thus, if we are to consider the everyday moments of the writing center, it is important to think about the negative, sad, and dark everyday moments that occur in the center as well.

I found depressing poems constructed on the walls, neglected plants, broken chairs, leftover and ruined works of art, old abandoned toys, and more. If Geller et al. call for writing center scholars to “remain open to everyday moments” in the center (56), I argue we need to make sure we’re attending to the dark, heavy, sad, and angry moments as well. They have just as much a place in the center as happy ones. In examining the dark everyday moments of the center evidenced through our interaction with objects in the center, I believe we can develop a better understanding of our consultants’ and writers’ states of mind. In addition, examining the objects of our offices and other workspaces within the center can help us to name some of the vulnerabilities we have likely been trying to repress or ignore. For instance, as I walked around taking photos recently, our writing center director asked me to take a photo of the yet-to-be unpacked boxes in her office, evidence, she said, of a lack of time due to a difficult semester (Figure 10).

Taking time to attend to the hidden and invisible acts of vulnerability in the center can open up space for writing center staff to begin conversing about how and why we might be hiding our negative feelings in the center, or how our space might reveal what negative emotions or actions are present in our workspace. Such conversations allow us to begin cultivating an understanding of a center that is not always a positive space, but a much more complex community.

Rachel’s story

During a recent session with one of my regular writers, I noticed that she was paying particular attention to the tchotchkes on the table in front of us while getting ready for the session. This writer is a graduate student and former consultant herself, so this attention perplexed me, since these items seem very natural in this space. Suddenly, she turned to look at me and said with complete seriousness, “What’s with the tissues on all the tables? Is this for if we cry?” (Figure 11).

The tissues aren’t a new addition to our tables, so I was struck speechless for a moment.

“I mean, do they think we’re gonna start crying during sessions or something?” she said, and forced a laugh.

But then I noticed something. Instead of dismissing herself with the same nonchalant tone with which she brought up the conversation, she used the tissues on the tables as a way to segue into a disclosure of how she is handling the stress of the semester—one of her final ones for her doctorate—describing how she feels like she can’t display her emotions in academia as a Black woman, and mentioning some challenges in her personal life. I sat. I listened. Then, she turned to me, and she sincerely asked how I was.

What a can of worms, I thought before I contemplated whether I should be honest with her, or give her the routine “I’m okay” answer that I’d been giving everyone lately.

I paused while she stared at me, waiting, and I decided I was safe.

I decided to be vulnerable.

I started working in writing centers in 2002, and I’ve held the gamut of positions from peer tutor to administrator. Along with all the joys that writing centers have brought to my academic and personal lives, like meeting lifelong friends in nearly all of the four centers in which I’ve worked, what I think about more often is how my 17-year writing center tenure has been punctuated by moments of implosion and forced vulnerability. These moments occurred when the façade of my strictly-orchestrated life fell apart in ways that were publicly unavoidable, and in ways that forced me to embrace my vulnerability in the writing center despite my position—a somewhat unwelcome gesture in a fairly emotionally-charged space.

Two implosions have left the greatest marks on my writing center life. In 2013, I was serving as the assistant director of a writing center at a moderately-sized southeastern university. I started work there in 2010 after leaving a lateral position as a way to shake up my life and, I thought optimistically, provide the change needed to save my failing marriage. Little did I know then that simply moving states and jobs doesn’t change your life. Alas, in the summer of 2013, I got divorced, and as sometimes happens with divorce, I decided to return to my maiden name. I remember sitting in my office one day, tissues in hand and tears streaming down my face, as I talked to my program assistant and dear friend. I was trying to figure out how to tell my staff that I was no longer going by the name they all knew. I had a new/old name. For me, it felt like a welcome return, but the majority of my staff didn’t know what was going on in my personal life, and I worried about the best way of relaying such intimate information. Of course, throughout this process, I couldn’t hide my face; daily, I carried around on my body all I was going through with my puffy eyes and tear-stained cheeks, and I’m sure my staff knew something was up.

After days of worry, I decided on an email simply and straightforwardly telling the staff what I was going through and what happened, to potentially head off any gossip that might occur. I chose to allow my colleagues into my life when I could have thrown up the walls around me even higher. Of course, my staff was empathetic, understanding, and welcoming of the new me; however, what I learned throughout this experience is that when we work in writing centers, we’re taught every aspect of how to care for our writers when they have meltdowns in our spaces, but we are rarely told how to care for ourselves when this happens . The needs of writing center tutors, administrators, and staff are made to feel secondary to the writers’ needs and desires, and I wonder if that’s how it should be.

Countless guidebooks and writing center training manuals show us what empathy toward a student looks like, but, perhaps ironically, they only relay one dimension of the friendly conversation that is encouraged in writing centers. Martini and Webster, in their introduction to The Peer Review special issue “Writing Centers as Brave/r Spaces” make note of the absence of guidance, particularly in guidebooks and manuals, for actually moving through the writing center space when they say:

Although these guidebooks often recognize the power dynamics at play (i.e., between tutor, writer, and instructor) and may acknowledge that not all writers are the same (i.e., offering advice for working with multilingual writers, adult learners, writers with anxiety, basic skill levels, or disabilities), most of the advice is prescriptive. Little, if any, attention is paid to how practitioners might act in response to intersectional identities or to the complexity of power dynamics across difference.

What, then, do we do with our complex emotional needs and those of our staff in writing centers?

The second implosion happened in January of 2018, when my mother passed away. When it happened, thankfully, I was with her and my father. I’m close with our administrators in the current center where I work, and upon her passing, they sent out an email to our entire staff and departmental faculty telling them what happened. Similarly to when I needed to tell my staff about my name change in 2013, my personal life was again the subject of a staff email—this time, though, not of my own choosing, and not coming from me. While the email, and my own subsequent Facebook post of the obituary, meant that my close friends could reach out to me during this time, it also meant that I had to deal with the “sympathy stare” when I returned to school one week after her funeral: colleagues, classmates, and professors who had no idea what to say to me or what to do with my sadness, and just stared at me with unwanted sympathy in their eyes. I found myself meeting the stare dead-on in defiance or getting caught smiling and nodding to the sympathetic friend, a way to reassure them that I was, indeed, okay .

As prepared as I thought I was to handle what happened in a space where the source of my grief didn’t happen, I was not. Every time someone would lovingly ask me “How are you?” or do a double take at me in the center, or look away when I caught them staring at me, I fought back tears and the urge to run away. Sometimes I didn’t win the fight, and I just let the tears come. Many times I simply sat at a window-facing table in the main consulting area of the center and cried openly as I stared out the window. Most people were scared to talk to me and skittish around me; rarely did anyone know what to do with me in this public space; writers handled me with kid gloves when they saw my face. I didn’t know what to do with myself, either, but I figured if there was ever a time to cry in the center, this was it. Right on time, though, the deep, shaming voice inside me quietly said that I needed to get it together at work, that this wasn’t the place, that I should save my crying, emotions, and vulnerabilities for closed doors, that my emotions and my vulnerabilities were unwelcome in this space.

Particularly in unwelcome spaces—like academia, conferences, or anywhere public—vulnerability can be seen as a weakness rather than a kind of strength illustrated through an emotive action or experience (like tears, laughter, or anger). However, one can choose to see the act of vulnerability in unwelcome spaces as a diffraction of sorts: vulnerability breaks apart traditional (heteropatriarchal, academic, etc.) norms and expectations while stitching together the fragmented, emotional pieces of oneself that have been shattered by an event. The diffraction provides us with a new way of seeing ourselves. It shows us that “there is no moving beyond, no leaving the ‘old’ behind” because it requires us to be honest and in touch with ourselves in ways that encourage us to remember the ‘old’ of our desires while living in the new” (Barad 168).

Most days, I don’t know if I’m ready to live with the new yet, but I am okay with sitting in the muck of my current state, even when it makes most people around me uncomfortable. This means that some days I need to cry in the center. I need to use the tissues at the table without shame or worry. I need to be visibly vulnerable with the people around me.

As I sat with my returning, graduate student writer that day and looked at the now-very-obvious tissues on the table, I made a decision. I leaned nearer to her and whispered, “Do you know what’s been going on with me this semester?” I never really know the best way to broach this topic now, so I tiptoed.

“No,” she said, taking a sip of her coffee, “What’s going on?”

“My mom passed away in January.”

“WHAT THE HECK ARE YOU EVEN DOING HERE?!” she exclaimed.

I gave her a weak smile and said, “I’m not really sure,” as I grabbed a tissue from the box (Figure 12).

Conclusion

In our own experiences, our vulnerabilities showed up in unexpected ways while we had to continue doing the everyday work of the writing center. Sharing these experiences in this chapter is a step toward what we would like to see writing center scholars continue to do: see and mark their centers as spaces where vulnerability is enacted on a daily basis. We conclude, then, with strategies for enacting and discussing vulnerability in other writing centers, based on some of the care-based practices central to Lauren’s work.

At the beginning of this chapter, we asked:

- What benefits are there to being vulnerable, and to acknowledging others’ vulnerabilities?

- Where are these moments of vulnerability in writing center work?

- When do we share our vulnerabilities, and when do we hide our vulnerabilities?

- What do vulnerable moments mean, and how do we navigate them with both empathy and action?

- What does it mean to be “vulnerable,” and does it look the same for everyone?

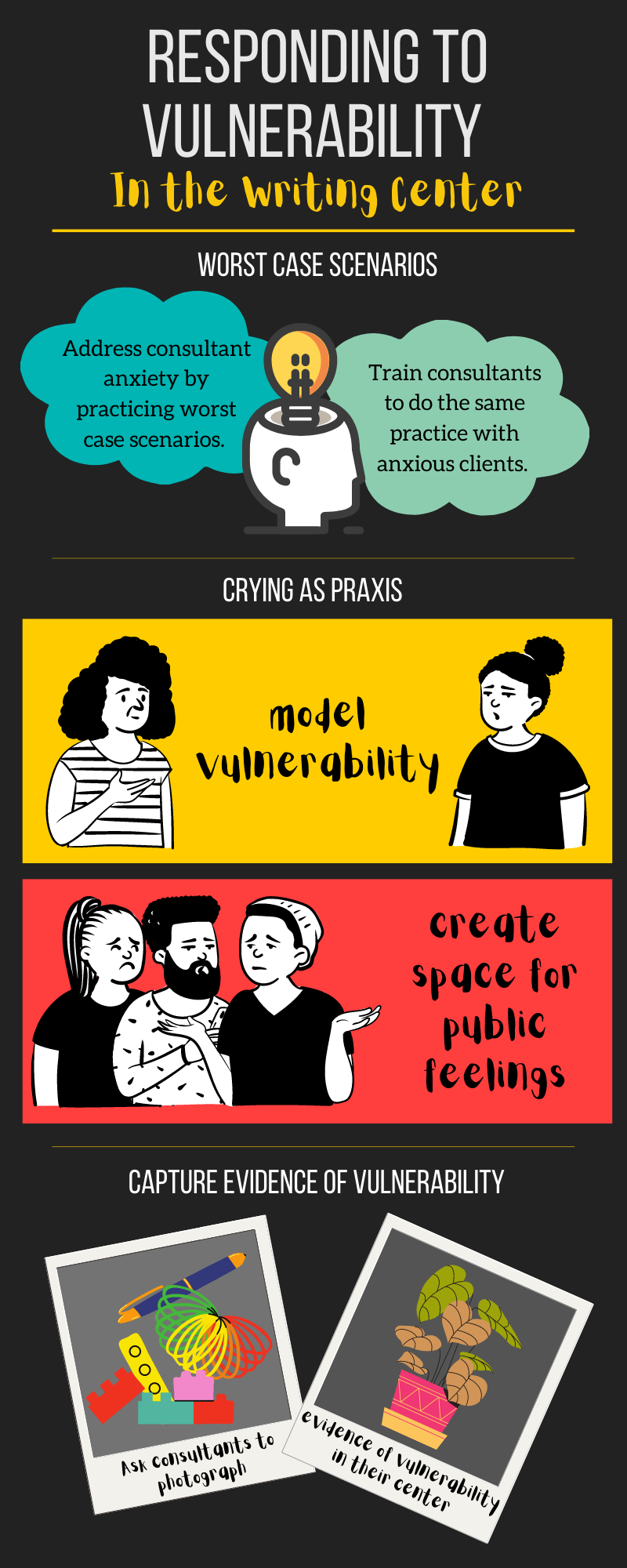

Below, we share three ideas for how vulnerability can be integrated into writing center work, and how we can better respond to vulnerabilities as listeners, consultants, and co-workers:

Cathartic Worst-Case Scenario Dump

There are multiple ways to enact a cathartic worst-case scenario dump. The first is by teaching your consultants to approach their anxieties about the writing center head-on by naming them, walking through their worst-case scenarios and working backwards through them. During trainings, consultants could work through their worries about sessions by running through worst-case scenarios with each other and considering how they might respond if such events happen.

One worst-case scenario for a consultant might be working with a writer who brings in a paper that is offensive (e.g., one that makes discriminatory comments based on race, gender, sexuality, or ability). During a cathartic worst-case scenario dump, consultants could first name their fear for this session: that the writer brings in an offensive paper and they do not know how to address these offenses. Then, others would validate this worry while also discussing strategies and solutions. This allows the consultant to find a support system within the writing center for handling these kinds of moments—so that if a moment they fear were to arise, the consultant has both strategies and support around them.

Another way to perform the cathartic worst-case scenario dump is during actual writing center sessions. Specifically, consultants can be trained to handle writers’ anxieties by having mock sessions where the writer brings in a work with a major writing worry. Then, the consultant can ask the writer about their worst-case scenarios and help work through those with them.

For example, if a writer came in with clear anxieties, the consultant might pause a session to ask about their worst-case scenarios (e.g., “I won’t finish this paper in time and will fail the course”). Then, the consultant can help address the writer’s vulnerabilities directly by working through them: “Let’s help you brainstorm some ideas for this paper and create a timeline so that you can get something written and turn it in on time.” This allows the consultant to use the writer’s vulnerabilities to create a conversation, rather than stall it. By acknowledging their vulnerabilities, consultants show empathy but also make a plan of action that writers can put into place.

In both cases, the cathartic worst-case scenario dump is meant to allow consultants or writers to share their vulnerabilities and worries while also giving them support to work through these worries in community with others.

Crying as Praxis

Consultants are often taught how to handle writers’ emotions during sessions. Some writing center guidebooks teach us that one of the many hats we wear is that of counselor. We are told that during sessions where writers have extreme emotional reactions we should “offer support, sympathy, and suggestions” and make sure we’re offering students access to the appropriate campus resources (Ryan and Zimmerelli 7-8). What is often left out of these scenarios is what happens when the consultant is the one having extreme emotional reactions. In these cases, we suggest that consultants be trained to handle themselves and their emotions with the same care and sympathy in which they would treat a writer, and to name those things when they happen during sessions or in the public spaces of the center. In other words, if a consultant feels like they might need to cry, don’t encourage them to rush out of the center to a private space; allow them to sit in the open and cry.

We understand that everyone handles their emotions differently. As writing center practitioners, we’re trained to understand this concept in sessions with writers (Ryan and Zimmerelli; Gillespie and Lerner). What we’re suggesting here is that consultants could also be trained to feel comfortable enough to step out of sessions, ask for space or time off, or openly share their stories with people they feel safe with when they have emotional reactions in the writing center space.

Training consultants to be sympathetic and caring of themselves is not easy. There are no simple steps or heuristic, and for some, approaching sessions without the comfort of an invisible mask will feel impossible, or even unsafe. Training consultants to be sympathetic and caring of themselves is not easy. There are no simple steps or heuristic, and for some, approaching sessions without the comfort of an invisible mask will feel impossible, or even unsafe. However, when administrators and other senior writing center staff model emotional vulnerability during sessions and in their everyday work, the ethos of the center will shift to one where reciprocal emotional sympathy is accepted and the center will start to feel like a space that is safe enough for others to test the crying waters when they need to.

Let us offer a point of clarity here: modeling emotional vulnerability does not always have to mean crying in public. For some, this can be an unsafe public act. Instead, we’re advocating for consultants to feel comfortable expressing their emotions (in healthy ways) in the center. This could be through tears, but it could also be in heartfelt conversations, expressions of frustration, or giggle fits.

Capturing Evidence of Everyday Vulnerability

Activity

- In a writing center training class or during a writing center staff meeting, ask consultants to take a few minutes to walk around the space of the writing center, taking pictures of objects that leave evidence of consultant or writer vulnerability (perhaps using the photos in this chapter as an example).

- After writers have taken their photographic evidence, have them share their findings with each other in groups (Figure 13), making note of what they think the photographs say about the feelings of the people who made them, and why they might be feeling this way.

Key Takeaway

* * *

We can’t guarantee that your center will become more vulnerable if you enact the strategies we have shared, but we do hope that these practices might allow you the space to see where vulnerabilities can show up among consultants in your writing center. By creating deliberate opportunities for vulnerability in these ways, and in other ways, we believe that the writing center can become a more empathetic and responsive space. In addition, we believe that our deliberate act of sharing our own vulnerabilities as consultants and administrators can help start a conversation about the emotions of our consultants, instead of merely discussing the emotional needs of the writers who utilize our center. We—writing center administrators, consultants, and writers—come to the center with emotions and vulnerabilities; being invited to share these experiences can create more community.

Works Cited

Barad, Karen. “Diffracting Diffraction: Cutting Together-Apart.” Parallax, vol. 20, no. 3, 2014, pp. 168-87.

Caswell, Nicole I., Jackie Grutsch McKinney, and Rebecca Jackson. The Working Lives of New Writing Center Directors. Utah State UP, 2016.

Cedillo, Christina. “What Does It Mean to Move?: Race, Disability, and Critical Embodiment Pedagogy.” Composition Forum vol. 39, 2018. https://compositionforum.com/issue/39/to-move.php

Craig, Collin Lamott, and Staci Maree Perryman-Clark. “Troubling the Boundaries: (De)Constructing WPA Identities at the Intersections of Race and Gender.” WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 34, no. 2, 2001, pp. 37-58.

Cvetkovich, Ann. Depression: A Public Feeling. Duke UP, 2012.

Denny, Harry et al. Out in the Center: Public Controversies and Private Struggles. Utah State UP, 2019.

Dixon, Elise, and Rachel Robinson. “Welcome for Whom: Introduction to the Special Issue.” The Peer Review, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019. http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/welcome-for-whom-introduction-to-the-special-issue/

Dolmage, Jay Timothy. Disability Rhetoric. Syracuse UP, 2014.

Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Duke UP, 2004.

Geller, Anne Ellen, et al. The Everyday Writing Center: A Community of Practice. Utah State UP, 2007.

Gillespie, Paula, and Neal Learner. The Longman Guide to Peer Tutoring. 2nd ed., Pearson, 2007.

Grimm, Nancy. Good Intentions: Writing Center Work for Postmodern Times. Heinemann, 1999.

Guarino, Kathleen, et al. Trauma-Informed Organizational Toolkit for Homeless Services. The National Center on Family Homelessness. 2009. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Trauma-Informed_Organizational_Toolkit_0.pdf

Halberstam, Jack. The Queer Art of Failure. Duke UP, 2011.

Herman, Judith. Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. Basic Books, 1997.

Laub, Dori. “Bearing Witness or the Vicissitudes of Listening.” Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis and History, edited by Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub, Routledge, 1991, pp. 57-74.

Love, Heather. Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History. Harvard UP, 2009.

Marback, Richard. “A Meditation on Vulnerability in Rhetoric.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 29, no. 1, 2010, pp. 1-13. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07350190903415149?journalCode=hrhr20

Martini, Rebecca Hallman, and Travis Webster. “Writing Centers as Brave/r Spaces: A Special Issue Introduction.” The Peer Review, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017. http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/writing-centers-as-braver-spaces-a-special-issue-introduction/

McKinney, Jackie Grutsch. Peripheral Visions for Writing Centers. Utah State UP, 2012.

Morales, Aurora Levins. Medicine Stories: History, Culture and the Politics of Integrity. South End Press, 1999.

Powell, Malea, et al. “Our Story Begins Here: Constellating Cultural Rhetorics.” Enculturation, no. 18, 2014. http://enculturation.net/our-story-begins-here/

Rowan, Karen, and Laura Greenfield. Writing Centers and the New Racism: A Call for Sustainable Dialogue and Change. Utah State UP, 2011.

Ryan, Leigh, and Lisa Zimmerelli. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. 6th ed., Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Smith, Carly, and Jennifer Freyd. “Institutional Betrayal.” American Psychologist, vol. 69, no. 6, 2014, pp. 575-87. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-36500-001

Tuhiwai Smith, Linda. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd ed. Zed Books, 2012.

Yergeau, Melanie. “Saturday Plenary Address: Creating a Culture of Access in Writing Program Administration.” WPA: Writing Program Administration. vol. 40, no.1, 2016, pp. 155-65. http://associationdatabase.co/archives/40n1/40n1yergeau.pdf

Appendix A

In-Text Hyperlinked Notes

Vulnerability: We acknowledge here that public vulnerability comes more easily to us than to some of our colleagues and friends of color. There are many types of vulnerabilities; some vulnerabilities we all experience through individual life moments, but different embodied identities may also present vulnerabilities due to discrimination, harassment, prejudice, and other forms of violence. Two of us (Elise and Lauren) are members of the LGBTQ+ community, and Lauren is disabled; these identities do affect when, and if, we can be vulnerable in certain situations, just as our privileged identities that we have as white people make us less vulnerable.

Professionals: From Lauren: It’s also worth noting here that the standards of professionalism are rooted in sexist, racist, neurotypical, and ableist notions of emotional distance, and that instances where we show vulnerability (often coded as a feminine act) are seen as not fitting for the workplace.

Social Justice-oriented practices in a writing center: We draw from the work of writing center scholars like Harry Denny et al. and Karen Rowan and Laura Greenfield, who claim in their own ways that writing centers can be third spaces where issues of race, gender, sexuality, language, class, and ability are meaningfully enmeshed in writing center conversations. We believe that writing centers, because of this liminal, third-space existence, are also spaces for those conversations to turn toward a social justice orientation.

We are not calling for everyone to always be vulnerable: It is the onus of the non-marginalized populations to create a safe enough space for these consultants to feel willing and able to discuss their vulnerabilities openly.

Care-based practices: For more discussion on care-based practices within university contexts, see the Two-Year College Association-Pacific Northwest’s 2019 newsletter, which outlines and discusses applications of trauma-informed values within institutional settings.

Died: From Rachel: Fortunately or not, for many of us, like Lauren and me, the writing center is often the space we’re in when alerted to bad or troubling news. The space then becomes filled with the (sometimes hidden) emotions of people experiencing this news.

I don’t actually get that job: From Elise: What I love about this is that you did get a job that values your vulnerability and trauma work. You get to be yourself there, be vulnerable in an academic space, and the students and faculty are better there for it.

Healing space: From Lauren: Here I use healing in a broad sense, recognizing the complexity and weight of the term. Many people prefer not to use “healing,” because it suggests that the vulnerability is a wound or a weakness to be covered up and disappeared, rather than something natural we use to learn and grow. I appreciate the idea of healing (-ing, not -ed) as a process rather than a state of being, however, and use the term to describe the interactions that we have with vulnerabilities and the process we go through to accept, work through, and live with these emotions.

Another abuser: From Elise: I certainly feel this, especially in this piece I wrote about sexual harassment and bisexuality a few years ago.

Larry Nassar: Larry Nassar is an American convicted serial rapist and sex offender, former USA Gymnastics national team doctor, former osteopathic physician, and former professor at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine.

For more information, visit https://www.michiganradio.org/post/timeline-long-history-abuse-dr-larry-nassar

I have seen some shit: From Rachel: Haven’t all of us graduate students seen some shit (some more than others, perhaps)?

Cried: From Lauren: The three of us also write about the specific act of crying in a forthcoming book chapter called “Crybabies in the Writing Center: Storying Affect and Emotion.” In it, we discuss crying as the same kind of vulnerable act we are calling for here, but also consider how crying comes with specific and complex power dynamics (who is crying and to whom?). But ultimately, crying, like many other forms of emotional vulnerability, presents opportunities to discuss social justice literacy, to form relationships and communities, and to reflect deeply on the emotions within our writing processes.

Michigan State’s Office of Institutional Equity: “MSU is committed to creating and maintaining an inclusive community in which students, faculty, and staff can work together in an atmosphere free from all forms of discrimination and harassment. File a Report Now.”

For more information, visit this link: https://oie.msu.edu/

Queer Comfort: From Rachel: I think you’re right in that many times people disregard negative feelings in times of misery, grief, and discomfort to instead seek out “positive vibes” in an attempt to feel better, but I’m really glad you pushed against this and sat in your discomfort and sadness for a little while. I think it ultimately helped you deal with your trauma on a deep level.

Tchotchkes: Yiddish term for a small group of items that are decorative and/or otherwise disposable.

How to care for ourselves when this happens: From Lauren: This reminds me of the idea of vicarious traumatization, or the act of being traumatized by prolonged exposure to other people who are traumatized. This often occurs with therapists or emergency service workers, who are taught that their first priority is to the person they are responsible for rather than to themselves. Similarly, in our “professional” settings, we’re taught to think of ourselves as workers, consultants whose job it is to help the client, our writers. But what happens when we put ourselves aside in favor of caring for the other person?

Okay: From Elise: I remember this time very distinctly because I saw those smiles and stares as invitations to talk with you about your mom and your grief. While many people were avoiding you or giving you a “sympathy stare,” this is when our relationship began to evolve into a very close friendship.

Window-facing table: From Rachel: I now affectionately call this my “grief table” in the center.

We acknowledge here that public vulnerability comes more easily to us than to some of our colleagues and friends of color. There are many types of vulnerabilities; some vulnerabilities we all experience through individual life moments, but different embodied identities may also present vulnerabilities due to discrimination, harassment, prejudice, and other forms of violence. Two of us (Elise and Lauren) are members of the LGBTQ+ community, and Lauren is disabled; these identities do affect when, and if, we can be vulnerable in certain situations, just as our privileged identities that we have as white people make us less vulnerable.

From Lauren: It’s also worth noting here that the standards of professionalism are rooted in sexist, racist, neurotypical, and ableist notions of emotional distance, and that instances where we show vulnerability (often coded as a feminine act) are seen as not fitting for the workplace.

We draw from the work of writing center scholars like Harry Denny et al. and Karen Rowan and Laura Greenfield, who claim in their own ways that writing centers can be third spaces where issues of race, gender, sexuality, language, class, and ability are meaningfully enmeshed in writing center conversations. We believe that writing centers, because of this liminal, third-space existence, are also spaces for those conversations to turn toward a social justice orientation.

It is the onus of the non-marginalized populations to create a safe enough space for these consultants to feel willing and able to discuss their vulnerabilities openly.

For more discussion on care-based practices within university contexts, see the Two-Year College Association-Pacific Northwest’s 2019 newsletter, which outlines and discusses applications of trauma-informed values within institutional settings.

From Rachel: Fortunately or not, for many of us, like Lauren and me, the writing center is often the space we’re in when alerted to bad or troubling news. The space then becomes filled with the (sometimes hidden) emotions of people experiencing this news.

From Elise: What I love about this is that you did get a job that values your vulnerability and trauma work. You get to be yourself there, be vulnerable in an academic space, and the students and faculty are better there for it.

From Lauren: Here I use healing in a broad sense, recognizing the complexity and weight of the term. Many people prefer not to use “healing,” because it suggests that the vulnerability is a wound or a weakness to be covered up and disappeared, rather than something natural we use to learn and grow. I appreciate the idea of healing (-ing, not -ed) as a process rather than a state of being, however, and use the term to describe the interactions that we have with vulnerabilities and the process we go through to accept, work through, and live with these emotions.

From Elise: I certainly feel this, especially in this piece I wrote about sexual harassment and bisexuality a few years ago.

Larry Nassar is an American convicted serial rapist and sex offender, former USA Gymnastics national team doctor, former osteopathic physician, and former professor at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine.

For more information, visit https://www.michiganradio.org/post/timeline-long-history-abuse-dr-larry-nassar

From Rachel: Haven’t all of us graduate students seen some shit (some more than others, perhaps)?

From Lauren: The three of us also write about the specific act of crying in a forthcoming book chapter called “Crybabies in the Writing Center: Storying Affect and Emotion.” In it, we discuss crying as the same kind of vulnerable act we are calling for here, but also consider how crying comes with specific and complex power dynamics (who is crying and to whom?). But ultimately, crying, like many other forms of emotional vulnerability, presents opportunities to discuss social justice literacy, to form relationships and communities, and to reflect deeply on the emotions within our writing processes.

"MSU is committed to creating and maintaining an inclusive community in which students, faculty, and staff can work together in an atmosphere free from all forms of discrimination and harassment. File a Report Now."

For more information, visit this link: https://oie.msu.edu/

From Rachel: I think you’re right in that many times people disregard negative feelings in times of misery, grief, and discomfort to instead seek out “positive vibes” in an attempt to feel better, but I’m really glad you pushed against this and sat in your discomfort and sadness for a little while. I think it ultimately helped you deal with your trauma on a deep level.

Yiddish term for a small group of items that are decorative and/or otherwise disposable.

From Lauren: This reminds me of the idea of vicarious traumatization, or the act of being traumatized by prolonged exposure to other people who are traumatized. This often occurs with therapists or emergency service workers, who are taught that their first priority is to the person they are responsible for rather than to themselves. Similarly, in our “professional” settings, we’re taught to think of ourselves as workers, consultants whose job it is to help the client, our writers. But what happens when we put ourselves aside in favor of caring for the other person?

From Elise: I remember this time very distinctly because I saw those smiles and stares as invitations to talk with you about your mom and your grief. While many people were avoiding you or giving you a “sympathy stare,” this is when our relationship began to evolve into a very close friendship.

From Rachel: I now affectionately call this my “grief table” in the center.