3 Imposter Syndrome in the Writing Center: An Autoethnography of Tutoring as Mindfulness by Benjamin J. Villarreal

Keywords: Autoethnography, imposter syndrome, mindfulness, tutors, tutoring, writing centers

Introduction

When I first started to realize that the amount of stress I was feeling was not normal, it was because of a little bookmark I had picked up at a campus health fair. One side had a list of common signs of stress, and the other had a list of things to do to calm oneself.

I still remember two of the tips because I used them often. The first was timed breathing: breathe in for four seconds, hold for two, and breathe out for five. I did this a lot once I realized that when I felt stressed my breathing shortened. It helped, kind of. The second tip: when feeling stressed, list five things I’d accomplished recently. It also kind of worked.

Some Ways to Manage Stress

- Engage in timed breathing

- List a set number (e.g. 5) of recent accomplishments

The bookmark became a talisman that I used to keep my place in whatever I was reading at the time, so that whenever I would open the book and get to work, I saw it and remembered the tips it offered—in the middle of class, on the subway, on the couch. Eventually, I stuck it under the glass top of my desk, so the five tips would be there looking back at me if I started to become stressed while working. And I decided I could stop being stressed, because I had five tips to walk through—easy-peasy!

Unfortunately, I had yet to realize that “tips” for fighting stress only work once you have some idea about what the underlying causes are. Unfortunately, I had yet to realize that “tips” for fighting stress only work once you have some idea about what the underlying causes are. I had yet to notice, consciously, that my most stressed moments were when my bookmark was nowhere near me, when I was getting ready in the morning or trying to fall asleep at night. And I had yet to recognize that I often couldn’t sleep because I was having or on the verge of having panic attacks (lying in bed, short of breath, the room spinning), let alone that I had been having them in some form since high school, if not earlier.

What I eventually learned is that I am most prone to stress when I feel like I am not occupied enough. And this realization led me to finally visiting campus mental health services, from where my bookmark came. I realized this in August of the fourth year of my doctoral program at an Ivy League university. August was always rough. The summer session at the college where I was an adjunct was over, the Graduate Student Writing Center (GSWC, a pseudonym) where I was a writing advisor was closed, and the pool where I taught swim lessons cut my hours as summer camps came to an end. And while the financial strain of all that was stressful, it was nothing compared to the anxiety I felt that I was accomplishing nothing, that I did not belong, that I was an imposter.

That understanding came much, much later. That August, I thought I was just worried about money. I was driving my partner crazy with incessant pacing and hand-wringing, and I figured I needed some additional tips that weren’t on my bookmark. And that’s pretty much what I told the intake-therapist; I just wanted some new ideas for managing my stress. She must have thought that was quaint because I spent the next few months digging into the roots of my stress, discovering that tips for managing it wouldn’t mean anything if I didn’t know what was really causing my anxiety. A few years later, packing to leave school for a tenure-track position, I found the bookmark amidst the piles of papers and notes that had accumulated on my desk and chuckled at it before tossing it in the trash. Like everything else getting chucked rather than packed, I felt like I could let go of that way of thinking, that my mental health could be solved by a list of suggestions that could fit neatly on a bookmark. The root sources of my anxiety are the subject of another paper, but suffice it to say, the idea of just needing tips to deal with stress seems so silly to me now.

The purpose of this autoethnography is to reflect on and elucidate for others how the GSWC became a personal space for practicing mindfulness that ultimately fostered a sense of belonging in me (a Chicano and first-generation college graduate), which in turn helped me cope with imposter syndrome, the sense that I didn’t belong at the institution. Finally, this autoethnography interrogates the choices I eventually made as a coordinator, redesigning the space in an attempt to foster that same sense of mindfulness and belonging for other students who shared or seemed to experience the same anxieties I felt.

To do this, following a discussion of autoethnography and some relevant literature, this chapter is organized into three vignettes: the first a sort of prologue and the other two broken up into my time as a writing advisor and then coordinator at the GSWC, with analysis and interpretation of both. These sections should not be viewed as strictly chronological but as overlapping timelines of my work at the GSWC.

Autoethnography

That I have chosen autoethnography as a means of conveying my research only seems to inflate my imposter syndrome. Unaware that such an approach even existed or that it “counted” as academic writing when I was introduced to it as an option, it made me feel both elated and suspicious. I asked the same questions my students now ask—isn’t that just personal bias? How is that generalizable if it’s just your experience? How do you verify what’s been written?

I offer my students the answers I’ve come to with mentors and on my own. Autoethnography allows one to confront one’s own bias; the point is not to be generalizable but specific. And the autoethnography’s verified by its readers and whether they share that feeling and experience or can at least understand those feelings and experiences. The piece I go back to most often for this is Carolyn Ellis and Arthur P. Bochner’s “Autoethnography, Personal Narrative, Reflexivity: Researcher as Subject,” which they also write as a personal narrative, exploring the ideas the chapter addresses by writing about their conversations with one another, students, and colleagues about writing personal narratives as a method. It’s a wonderful piece that I find helpful and grounding whenever I’m feeling doubts about autoethnography.

What I don’t tell my students is that there are days when I don’t believe these answers. I experienced several of those days when writing this chapter: “Who cares about one privileged doctoral student’s anxiety? I shouldn’t have even approached this topic till I interviewed my colleagues ‘cause I bet I was the only one who felt like that! I’m just outing myself that I don’t really belong in the academy because a) I wrote a whole chapter about feeling that way so it’s probably true, and b) I’m doing non-generalizable narrative research that’s only recently begun to be taken seriously, and even then only by those who also do it!” But I don’t tell my students about these self-doubts. And that’s part of the larger problem this chapter hopes to address—acknowledging our imposter feelings. And that’s part of the larger problem this chapter hopes to address—acknowledging our imposter feelings.

Ellis and Bochner suggest autoethnography might be one way of accomplishing this, explaining, “By exploring a particular life, I hope to understand a way of life” (737). In the case of autoethnography, that “particular life” is the author’s own. Ellis and Bochner further explore variations on this, including the “literary autoethnography,” in which “the text focuses as much on examining a self autobiographically as on interpreting a culture for a nonnative audience” (740). In other words, such research is about the author trying to understand themselves and their place in a culture to better understand that culture.

“The goal,” Ellis and Bochner explain, “is to encourage compassion and promote dialogue” (748). They further note that the author, hopefully, can better understand themself, as such reflection should raise questions like, “What are the consequences my story produces? What kind of person does it shape me into? What new possibilities does it introduce for living my life?” (746) Sharing that understanding, the author creates a space where readers can also better understand as they enter the conversation around that experience. Concerns about generalizability are addressed by readers, as “they determine if [the narrative] speaks to them about their experience or about the lives of others they know” (751). In other words, while autoethnographies allow the author to better understand themselves within the culture they study, they hopefully also help readers understand those within the culture as well. While autoethnographies allow the author to better understand themselves within the culture they study, they hopefully also help readers understand those within the culture as well. Further, if readers are already steeped in the culture, hopefully the autoethnography validates their own experiences and offers other ways of interpreting those experiences.

For my part, I share my stories about imposter syndrome, graduate school, and writing centers in hopes that they resonate with others working in and around the same circles by offering them a new way of seeing those spaces. My own experiences in these spaces have been validated by those I have worked with in them, so by delving into my experiences here (rather than, say, interviewing others for their stories), I hope I can better understand how they, as well as others I work with in these spaces (e.g., colleagues and my own students), continue to influence me now.

Finally, as this was not a subject I planned on writing about as a doctoral student, I now rely primarily on my scattered journal entries and own memory as the primary means of reflection and interpretation. For that reason, this chapter is purposely written as my story in the GSWC and not the story of the GSWC. Though they are intertwined, the larger narrative would require more voices to tell—voices I am now, hopefully, better prepared to hear, having completed some of the work of interrogating my experiences. To this end, I have left out details of the GSWC, the people there and at Ivy University, deidentifying them as much as possible and weaving multiple people together where possible (in this regard, the pronoun “they” is used throughout as both a gender-neutral singular pronoun and a plural pronoun).

A Review of Relevant Literature

The seeds of this chapter were planted in small observations I made about myself and the GSWC starting from my first days as an advisor there. But just as I did not then have a name for imposter syndrome, I did not have a name for a lot of the ideas that were rattling around in my head. When I took over as coordinator after three years, I made reading as much writing center research as I had the time and budget for a priority. As a result, the research that led to me putting these ideas together is a mixed bag.

Perhaps fittingly, this is less a “literature review” and more a discussion of the research that helped me make sense of my experiences. Some were suggestions I stumbled upon in the WCENTER listserv; others were dropped in my lap like those in the call for papers for this piece. I went looking for research on imposter syndrome once I knew there was a name for what I was feeling. I begin with a broad discussion of imposter syndrome and then narrow my discussion to the ways marginalized students might be particularly affected by feelings of inadequacy. Finally, I discuss mindfulness and how it fits within discussions of writing center studies.

But first, a definition: in their landmark 1978 piece “The Imposter Phenomenon in High Achieving Women,” Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanne Ament Imes define what they call the “imposter phenomenon” as “an internal experience of intellectual phoniness” (241); Elizabeth Cox’s TED-Ed lesson “What is imposter syndrome and how can you combat it?” provides a quick look at Clance and Imes’ research, as well as more current research.

While Clance and Imes’ work looks at high-achieving women and the reasons for their perceived lack of qualifications, despite all evidence to the contrary, the imposter phenomenon has now been labeled a syndrome and is understood to be prevalent in academia. One of the most interesting parts of the article, however, is a footnote on the first page: “The question has been raised as to whether or not men experience this phenomenon…We have noticed the phenomenon in men who appear to be more in touch with their ‘feminine’ qualities’” (Clance and Imes 241).

But times have changed since 1978, and a quick search on The Chronicle of Higher Education shows a number of articles summarizing advice for addressing imposter syndrome and related issues, aimed not only at women but at men at multiple levels of academia (from students to faculty). One such piece, Sindhumathi Revuluri’s 2018 “How to Overcome Impostor Syndrome,” offers tips such as “Compare like to like” (meaning, for example, that a new graduate student shouldn’t compare themself to another who is about to graduate) and “Think about the factors that could contribute to feeling like an impostor.”

Elaborating on this second example, Revuluri cites the 2013 research study by Kevin Cokley et al., “An Examination of the Impact of Minority Status Stress and Impostor Feelings on the Mental Health of Diverse Ethnic Minority College Students.” Cokley et al. studied 240 ethnic minority college students, finding that while the degree to which different ethnic minority college students felt minority status stress and imposter feelings varied, “both significantly correlated with psychological distress and psychological well-being for all of the ethnic minority groups” (91). In other words, ethnic minority students are prone to imposter syndrome and may be more likely to experience mental health issues because of it.

Similarly, Georgann Cope-Watson and Andrea Smith Betts’ 2010 autoethnography “Confronting Otherness: An E-conversation between Doctoral Students Living with Imposter Syndrome” mines the researchers’ own emails as data. A key finding is that what is often perceived as “merely self-doubt” experienced by a few may be how imposter syndrome is traditionally minimized by the academy and society. By way of example, the researchers note that:

Parallel to the essentialist concept that assumes women are the family caregivers is the patriarchal concept that women will assume the role of primary caretaker of the family and the children. These “old norms” (Acker & Armenti, 2004, p. 18) operate in ways that make it difficult to be both a mother and an academic. Bell (1990) recognized that sex-role expectations of our culture frequently give women conflicting messages about achievement making it difficult to internalize success. (9)

Drawing on Clance and Imes, they conclude that women who cannot juggle both family and academia with “ease” (qtd. in Cope-Watson & Betts) end up feeling that they are not suited to being scholars. And while Cope-Watson and Betts write specifically about women, this does suggest that any scholar who does not meet familial or cultural expectations of success may feel that they must not belong.

For this reason, a key component in pushing back on imposter syndrome is mindfulness. A key component in pushing back on imposter syndrome is mindfulness. Jon Kabat-Zinn defines mindfulness as the “awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally.” Being able to reflect “non-judgmentally” on reasons for feelings of inadequacy (e.g., not meeting familial expectations), particularly in the here and now (e.g., expectations as a scholar), may lay bare the conflicting senses of identity contributing to imposter syndrome. As this relates to writing center studies, Jared Featherstone et al. describe the mindful writing advisor in the “The Mindful Tutor”:

In the writing center, a mindful tutor would notice when planning, fantasies, and commentary are compromising their attention and use an attentional anchor, such as the sensation of their feet touching the floor or the movement of their breath, to stay present and focused on the client’s words. When self-doubt arises, the mindful tutor acknowledges and accepts this mental pattern but does not let it interfere with the process of helping the client with a writing assignment. With this reduction of mental noise and ability to self-regulate attention, a tutor can remain focused on the collaboratively established goals of the writing center session.

The key takeaway here lies in that attention to the task in front of a tutor can help mitigate imposter syndrome they may feel during the session.

Early Days

By my second semester of doctoral work, I was adjuncting at a community college across town, then racing back for classes and work at the GSWC. And I was drowning in reading. I have never been a quick reader; even in my English Literature MA program, I languished behind my peers. I often felt like it was all I could do to finish the weekly reading in time for class, never mind having an interesting analysis to share. Even that was difficult; often, unable to finish whatever novel we were discussing before class began, I resorted to reading a plot summary so that it wouldn’t be obvious I hadn’t read the ending. I hated doing this, but I also didn’t really know what else to do or how else to keep up with the work. (I later learned I was reading “wrong” because I was trying to read everything, and my professors helped me develop better reading strategies.)

I felt that way again in my doctoral program. I drifted through that first semester, alternating between excitement about what I was learning but defeated to find out that I seemed to have learned it so much later than others, who were now two or three steps ahead of me. And it wasn’t just that they seemed to understand the material better than me; it was like their whole lives had brought them to this place, to this moment. The classroom was full of people who’d been on championship academic teams, published articles, poems, essays, and already had solid employment in our field. And this felt true even of the peers in my cohort, all of whom constantly spoke up in class with meaningful contributions, week after week. And here I was, some Chicano kid (I also soon realized I was one of the youngest people, if not the youngest, in my program), whose parents hadn’t graduated college, reading and writing about things my peers all seemed to know more about. And I felt this way despite that: my dad’s work had enabled me to attend private schools K-11; I’d worked multiple jobs to pay for college, applying for every scholarship I could; I was hired by my masters institution after graduation. Yet I didn’t feel remotely in same league as my peers.

A day or so before Christmas, I turned in my last assignment. My seminar professor had given the class an extension, first to the last day of exams, then Christmas Eve, then December 27th, and finally offering us an incomplete and a whole year to finish it. At first, I thought this was a joke, but when my peers chuckled not from humor but relief, I was worried. I looked at my own work, which I knew wasn’t amazing but was also, I thought, almost done. I’d certainly have it finished by the original due date. But the more time the professor gave us to work, the more I felt I had to work on it. All that extra time meant they expected that much better work, right?

I later learned that my program stressed the practice of the writing over the product. This became clear when another professor explained that their expectations for final papers on existing research were different from their expectations for new projects. But that first semester, I was distraught.

In a moment of frustration, anger, exhaustion, I don’t know what, I decided I wanted to be done with the project before Christmas. A couple of days in a row, with my other assignments finished, I left my desk only to attend campus holiday parties for the free food and to walk my dog. Once I had turned in the assignment, I had completed my last shift (I forget at which job), and I had nothing to do but celebrate until I went back to work in a week, I cried tears of relief and disappointment with myself. The first semester was over.

Writing Advisor

When I first applied to the GSWC, it was as an office assistant. I’d seen the job listed under work study positions and sent in my materials. I had been in my doctoral program less than a month and was still trying to cobble together a meaningful paycheck. I’d moved to school at the end of the summer and managed to find steady employment as a lifeguard and swim instructor. I’d been asked for an interview to teach English as an adjunct at a nearby university before moving, but they’d filled the job by the time I got there. Then summer camp ended, and my hours at the pool were cut.

So I was very excited when I went in to interview to be an office assistant and instead was offered a writing advisor position, for better pay. The supervisor saw that I had lots of writing center experience from my masters institution and that I’d helped revise our tutor handbook. Plus, I had an MA in English and was getting my doctorate in English Education; I would later learn that this was an anomaly. Ivy University had over 80 graduate programs across the disciplines, and the cross-section of writing advisors reflected this. The GSWC wasn’t housed in an academic department, and the coordinator’s job description was more administrative than research based. So, they were interested in what I would bring to the position given my experience and research interests.

Still, I was a little uncertain; aside from my MA peers, I’d only worked with maybe one or two graduate students, and whether that was once or over multiple sessions, I can’t remember. The supervisor reassured me that working with graduate students wasn’t all that different from working with undergrads: read their work with them; stick to higher-order concerns like rhetoric, structure, and organization; don’t edit, but listen for the kind of help they need. And if their concern lies outside of your field, say so.

I was still unsure, but largely speaking, I found they were right! The one major difference was that most grad students seemed to want to visit, with only a few coming, grudgingly, at their professor’s insistence. I went to several of the Saturday morning workshops on specific writing topics that other writing advisors ran as part of my training. I learned about concept mapping and the common features of academic writing across the graduate curricula. But aside from field/discipline-specific questions, I found I could help most writers who came in, especially once I really familiarized myself with APA style and formatting, having only ever used MLA in the past.

It helped, too, that I had a lot of down-time that first semester. Later I realized that the other advisors had their regulars, writers who came to see them at the same time and same day weekly or bi-weekly. As the new guy, I didn’t see many writers that first semester. Once or twice a shift, someone (usually who’d never been to the GSWC before) would have an appointment, and being the only free advisor, I’d work with them. Otherwise, the regular writers only came in when they knew they could work with their usual advisor. When not working, we were pretty much free to spend the time however we wanted, and this turned out to be kind of a blessing.

I used this time to catch up on my own work, play a mobile game when I couldn’t read anymore, or just doze off, often whether I wanted to or not; at the time, I wasn’t sleeping well or all that much. I was happy to be getting another paycheck, but I also felt like I wasn’t really earning it. In a given shift, one of my coworkers might see three or four writers to my one. My supervisor, to their credit, assured me those days were numbered once new writers visited and connected with me. Eventually, the supervisor also redirected some of their regulars to me, and I worked with some of those writers for years. But that first semester, I was worried they weren’t going to hire me back. Why pay someone you don’t seem to need?

When I first started working in the GSWC, I also realized that there was very little I knew about writing in other fields. When I first started working in the GSWC, I also realized that there was very little I knew about writing in other fields. My supervisor had warned me not to give advice on things I couldn’t, that my job wasn’t to be an expert in the writer’s field—that was the writer’s job. Mine was to help them develop or revise what they had already written or brainstorm new ideas they could write about. I got really used to saying, “That’s a question for your professor.”

Despite that, I quickly realized I could still help, even if only with sentence-level features. I was able to recognize when evidence was provided for a claim but failed to explain how it supported the claim; when a summary was missing vital details; when an introduction did not match the body.

The first time I heard the words “imposter syndrome” was in an Introduction to an Academic Writing workshop my supervisor ran. I was attending these workshops as all new advisors did so that our advice was more or less on the same page. While many attendees, myself included, expected a crash course in the “rules” of academic writing, there were too many programs and fields for those rules to be true even among half of the attendees. Instead, the workshop was more about strategies for the kind of writing that graduate school required—lots of it, done quickly and well.

When the coordinator jokingly defined imposter syndrome (I think, simply as, feeling like you don’t belong, will be found out, and shunned), it was like lightbulbs went on around the room. Around me, writers nervously chuckled and/or scribbled the words down in their notebooks. I immediately thought of my MA peers and feeling like I was just pretending I belonged there—sure that, at any moment, my professors were going to realize what a mistake they’d made admitting me. And I realized I felt the same way now in my doctoral program. Now I knew its name.

Eventually, somewhere during that first year, I started to figure out that I was helping graduate students, some of the brightest and most brilliant minds in the world, improve their writing. By the end of my first year, my supervisor invited me to our monthly workshops not as an advisor-in-training but to think about how I might lead the same presentations. In my second year, I was asked to co-present, and by the end of that year, I was leading them myself.

I’m not sure when I realized that I was not only presenting to twenty to thirty students from different programs and even different countries but that I had answers to their questions; when I responded to their questions, I felt like I’d arrived. Over the next few years, I was asked to give more presentations (including at student orientations, a conference for minority graduate school applicants, and a seminar in the library’s education think-tank).

At the same time, I felt more confident working with writers one-to-one. They brought in such fascinating research that I couldn’t help but be absorbed in it. And in helping them find their best way of presenting it, I learned about things like the social studies curricula of other countries, urban food deserts, and therapeutic interventions for movie characters with mental health issues. People started to recognize me: students, faculty, staff. They would stop me in the halls, on the sidewalk walking my dog, introduce me to whoever they were with. People knew me and knew I helped with writing.

Interpretations

I’d already known for a long time that teaching is one of the only things I do where I feel total presence on a regular basis. No matter what concerns, worries, and frustrations I’m feeling, usually within a few minutes of class starting, my attention and thoughts are on the students in front of me, on the material. I noticed this for the first time when I had to teach while knowing that after the class, my partner and I would be receiving life-changing news, the waiting for which had consumed our attention for a week or more. But once that class began I started in on the day’s lesson, it was like that anticipation was put on hold. I didn’t think, worry, or even consider it, so much so that when class ended, I suddenly remembered the news, and my heart was off racing again.

After a couple of years in the GSWC, I started to notice the same thing would often happen when regularly working with the same writer. After finding out how they were doing, what they were up to outside of work, and sharing the same, we would dive into their draft, and I was in it.

This was long before I knew about or understood mindfulness. Now, I look at my teaching, and particularly my writing advising, and see those moments as practicing a kind of mindfulness. Featherstone et al. describe “attentional anchors” as key to maintaining mindfulness during tutoring. For me, the attentional anchor was the writer’s work. What had once caused me to doubt my place became the thing that grounded me: being surrounded by the brilliant, inspirational work of my peers. But the same happened when working with groups of writers, as well.

I would go on to lead the Introduction to Academic Writing workshop (or some variation of it) myself dozens of times before leaving the GSWC, and it remains my favorite regular presentation. In many ways, I think adapting my supervisor’s version and then revising it for myself became the first act of writing this chapter. I still discussed things like reading strategies and basic citation and creating deadlines, but I also tried adding elements that would normalize the kind of self-doubt instilled by my imposter syndrome. Many of these additions were simply gifs and memes or jokes spoken aloud in between slides or when answering questions, but they seemed to get good responses (both in the moment and in evaluations). And whenever I brought up and described imposter syndrome, I saw the lightbulbs go on, eyes widen, nervous chuckles, and mad scribbling; I’d passed on the name of the thing. Knowing it makes it less scary.

And despite my own imposter syndrome, my work for the GSWC became a space that affirmed my own belonging. By working mindfully with other writers, I could see them grow as scholars, which affirmed for me that I did indeed belong there among them. And despite my own imposter syndrome, my work for the GSWC became a space that affirmed my own belonging. By working mindfully with other writers, I could see them grow as scholars, which affirmed for me that I did indeed belong there among them. And this newfound confidence spilled into my other work, my teaching and my research, so much so that I even defended my dissertation in the GSWC. I also didn’t want to monopolize that feeling; I wanted to share it. But I’m no longer sure that sharing it should have been my goal or that it was my place to do so.

Coordinator

The summer before the fourth year of my doctoral work, I was promoted to the position of coordinator of the GSWC at Ivy University. I was excited but also immensely stressed about the coming fall. Despite how far I felt I’d come in terms of my work and belonging, the imposter syndrome returned. I felt like I wasn’t really the best person for the job—just the only person there to do it. That August, I finally went to campus mental health services. It helped, almost immediately, to just talk about the things that worried me so, and to have them validated. And by mid-fall, I felt like I was seeing academic stress in a whole new light; I knew, too, that I wasn’t the only one feeling it. And this revelation about my own academic stress added to my desire to make the GSWC not just a space where I felt safe and affirmed in my work but where the rest of the staff and visiting writers did too.

From even my first days as a writing advisor at the GSWC, one of my immediate concerns was space. I’d come from a writing center where tutoring occurred almost entirely in open spaces. There were cubicles at the back of the room, but most of the tutors, myself included, preferred discussing writers’ work at the coffee table or the large desks. When I arrived at the GSWC, I quickly saw that each advisor had an office that was unofficially theirs, shared with another advisor on alternating shifts. Not wanting to throw off the harmony, I took the only unoccupied room. It had a table and chairs, but it also served as a storage room, with wire shelves on two walls. And the room was small enough that if someone entered without taking off their bag first, they were likely to get caught on something: the door, a shelf, a chair. Because one of my concerns as a new coordinator was space, I turned to the literature on writing center studies. One of the first books I picked up was Jackie Grutsch McKinney’s Peripheral Visions for Writing Centers.

Grutsch McKinney’s work blew my mind (so much so that I’m still a little mortified by how I gushed when I later met her at the Conference on College Composition and Communication). One of the first things Grutsch McKinney challenges is the narrative of writing centers as comfortable spaces. While I understood her point when I first read the book, our center felt so far on the other side of the continuum that I worried visitors were embarrassed to be there; closed doors and hushed tones were the norm. The story the space told, as Grutsch McKinney puts it (21), was that the center was clinical, and remediation was something that should take place behind closed doors. When we tried 15-minute walk-ins in the library (in other words, when we brought tutoring to students), no one talked to us in public. I knew I wanted to redesign the space in response to this, but I also didn’t want to ignore Grutsch McKinney’s warnings around the “cozy home” (20). Importantly, she pushes back on some of the writing center’s most time-honored stories, such as: “writing centers are comfortable, iconoclastic places where all students go to get one-to-one tutoring on their writing” (6). In doing so, she argues not only that such stories limit what writing centers can be but that some users may want or need their writing center to be something different.

Equipped with Grutsch McKinney’s lens for analysis, I looked to the advisors, my supervisor, faculty, and writers at my university for what story the GSWC told. Grutsch McKinney’s book pointed me to James A. Inman’s “Designing Multiliteracy Centers: A Zoning Approach,” which demonstrates what writing centers can borrow from city design by breaking the space into “zones” dependent on what users will do in them. Like Grutsch McKinney, Inman pushes back on the narrative that writing centers need “round tables, art, plants, couches, and coffee pots” (Grutsch McKinney 21) without consideration for what purpose they serve.

Inman concludes with a “methodology” for “designing center spaces”:

- Make a list of important uses of your center;

- Review a blueprint or floorplan of your center, and make decisions about what uses should be supported where;

- Present your plan to stakeholders, soliciting support and ideas for revision;

- Once a final plan has been approved, implement it consistently; and

- Keep an eye out for necessary revisions to the plan, which should also be approved by stakeholders. (28)

Combining Grutsch McKinney’s ideas with Inman’s, I knew that going forward, what I didn’t want was for visitors to the GSWC to feel embarrassed to be there. That became the root of our redesign. Grutsch McKinney and Inman offer reasons for rethinking how writing centers design their space in order to better serve their users, including those users with imposter syndrome.

In addition to physically redesigning the space, I also wanted to change and add to the programming and retrain the staff. My hope was that all of this would make the GSWC a space where writers didn’t feel bad about visiting and staff felt like they were growing while helping their clients grow. The easiest of these was training; the majority of the staff had actually graduated and left right before I took on the coordinator role, which meant I got to hire and train a new staff almost from scratch. I learned that we nearly always got more applications than we could take on, so I was able to not only hire experienced writing advisors but people who were invested in the work of helping others too (without divulging individual advisors’ programs, many were from helping and educational fields).

Questions for Discussion

- Discuss the features of your most satisfying tutoring experiences.

- In what ways might a writing center’s space and layout factor into positive tutoring experiences?

We discussed the features of the most satisfying advising experiences (in which both advisor and writer seemed to get a lot from the session) and how to redesign the GSWC and our protocols to create space for more sessions that would be satisfying in the same ways. This included an end to closed-door sessions; we also got rid of extra stuff that had accumulated in the various offices: fake plants, unnecessary shelving, extra desks and chairs. We tried to turn the “waiting area” into a space that encouraged conversation over tense silence by opening it up: again getting rid of unneeded stuff, adding a coffee pot, and painting one wall with blackboard paint. We used this blackboard wall for meetings, but also added regular prompts where writers could share their feelings about writing, what they were working on, etc. Because doors were no longer closed and the waiting area had more space, it became a hang-out spot where writing advisors and students checked in with one another between sessions. But we also kept a small table in the corner of the waiting area where someone could work quietly, away from the couch and coffee maker, if they wanted; here we also put up magnetic poetry, and eventually, it became commonplace to find a writing advisor sitting there contemplating word choices on a slow day. We also added new programming to address specific concerns, such as how writers could direct their sessions. It didn’t happen overnight, but the GSWC changed a lot that year.

One of the things that made me happiest was coming in on Friday afternoons. I often didn’t need to be in on Fridays; it was our slowest day to begin with, and we often had cancellations or no-shows. If I did go in, it was usually just before or after visiting my partner who worked in the campus library, a 5-minute walk away. When I did, I would frequently be greeted by excited conversation and laughter heard down the hall, the writing advisors hanging out in the waiting area, sitting on the couch, chairs, even on the floor, some lingering even after their shifts had ended. Sometimes, they would be laughing or commiserating over something said by a politician, a meeting with an advisor gone poorly, or stress about schoolwork. Regardless, this always made me happy.

We tried hosting a Scrabble night, hoping to bring in some new faces. No one showed up. But the staff and I sat around eating the snacks we’d ordered, playing a giant game of Scrabble on the floor. Somewhere in there, we began to realize that we were a group of hardcore tabletop gamers, and I’m not talking Clue or Monopoly. Thus began plans for our first staff game night at a local board game bar, which also began the GSWC’s obsession with The Resistance (Eskridge), a game in which players form a guerrilla organization and try to take down a dystopian state. The catch in this game is that some of the players are double-agents, trying to sabotage the resistance (literal imposters). Each round is a game of finger-pointing, clever lies, and general frustration. But they loved it. (They also loved a weird children’s game called Unicorn Glitterluck, but I’m not going to touch that.)

For months after, the staff referenced the rounds we’d played. They immediately began planning our next staff game night, which became a once-a-semester occurrence, usually around finals. We also started holding our monthly meetings off campus, the advisors taking turns leading them, in hopes that both would create space for ideas that might not come to light otherwise. A few of us who were already working on our dissertations even formed our own writing group, taking turns sharing sections and then meeting to discuss them, or just meeting and all writing silently but together. The GSWC became its own little academic support group. I felt like I’d played a part in bringing the group together by creating a space I had needed but that hadn’t existed when I first started working in the GSWC.

Interpretations

One of the things I realized when working with graduate writers was that many (if not most) seemed to be as full of self-doubt (if not more) as me. Somewhere along the line, I realized my own imposter syndrome couldn’t just be addressed by helping other graduate students feeling the same way. My imposter syndrome went back to my earliest days of grad school (probably undergrad too), though I didn’t know it then, of course. But in trying to interrogate my imposter syndrome and how it influenced me then as well as continues to influence me now, I have to acknowledge that I may have created a pitfall for myself: did I create a writing center space in which the staff and writers felt like they belonged (combating their potential imposter syndrome) or did I create a writing center space in which I felt I belonged? These questions were something I was concerned with even then. And now that concern has grown.

Question for Discussion

- Do you feel a sense of belonging in your writing center?

But these changes seemed to work. After redesigning the GSWC, walk-ins became so popular that we often had to turn people away. Writers stopped asking to close the doors; conversations started and ended in the previously silent waiting area; writing advisors started asking each other for help. The feedback we received on anonymous surveys of individual sessions and evaluations of workshops (which I checked weekly with an almost obsessive concern) largely suggested that the main critique was that we didn’t have enough availability.

However, I won’t claim there’s a causation or even a correlation between our redesign and the increased usage and positive feedback; there are simply too many other factors to consider, from changes in funding, our university as a whole, global events that found their way into writers’ work, or even just an increased social media presence by the office that housed us. What I will say is that the changes in the community made me feel like I had accomplished something — like I had made a writing space that people wanted to visit and where they felt affirmed as writers and scholars, as opposed to leaving the center embarrassed.

Did I still make the GSWC a “comfy space” despite Grutsch McKinney’s warnings? Well, I did add a coffee maker, put up less abstract art, and throw out fake plants, but we were kind of stuck with the soft couch and round tables. The people, though, were different. Sure, we added a blackboard covered in affirmational messages that staff and writers added to and doodled on, but would the old staff have used it? One of the things that seems absent from Grutsch McKinney’s chapter on writing center spaces is the staff as “users” of writing centers. While, of course, the visiting writers are our key pedagogical concern, many tutors are also students. Shouldn’t we consider what’s best for them as well?

In their piece “Opening Closed Doors: A Rationale for Creating a Safe Space for Tutors Struggling with Mental Health Concerns or Illnesses,” Hillary Degner et al. argue for just that: “centers have ethical obligations to 1.) create environments where tutors, as well as students, grow and 2.) recognize mental health concerns or illnesses as part of the status quo, and not as conditions that are abnormal.” They urge the importance of staff training in recognizing mental health concerns both in themselves and among visiting writers, as well as knowledge of campus services.

The GSWC wanted to start such initiatives, but I was not fully able to begin implementing them before my time as coordinator ended. We discussed these matters in staff meetings, and I endeavored to make clear that their mental health was just as important as the writers they worked with — and that they should let me know if they were feeling overwhelmed. That some took me up on this, asking if someone else could take their sessions on difficult days or if we could discuss a particular session that they felt had not gone well, suggests not only that it was important to have those conversations but that staff felt comfortable doing so.

I now realize, however, that I often did this to the detriment of my own well-being, such as taking on another advisor’s sessions when I was already feeling overwhelmed. My therapist at that time helped me see this, and it was around this time that it became clear that more formal mental health awareness training (as opposed to just conversations during staff meetings) was necessary.

Though Degner et al. mention the importance of such training in 2015, back then, I was mostly unaware of where to get it. I knew of a colleague at another writing center who held a kind of social work-based training for their staff, and we tried but were unable to piggyback on this. And unfortunately, like many of the plans I had for myself and the GSWC, it fell by the wayside due to lack of time and other seemingly more immediate concerns.

Taking this back to the question of whether I created a space in which the staff and writers could feel a sense of belonging or just a space in which I felt I belonged, I suspect it was a little bit of both. That evaluations of not just my work but the staff’s were so consistently positive, that open conversations were happening for seemingly the first time, suggest to me that my efforts were well-received. But I’m not sure I didn’t just create a space that worked for me that happened to work for others as well. In short, I was not, as Beth Daniels puts it, “careful of literacy narratives that make us feel good” (qtd. in Grutsch McKinney 25).

Conclusions

I accepted a tenure-track position at my MA alma mater still all-but-dissertation (ABD), thanks to a loan-for-service state program for minority doctoral students that my alma mater had sponsored me for. This in itself — that I did not go through the stressful academic job hunt so many of my friends faced — was another source of imposter syndrome. To battle the feeling of imposter syndrome, I had to constantly remind myself (and be reminded by others) that I had been through a stressful period too: not only had applying for the loan-for-service program been difficult, but I had to apply for it at least three times before receiving it.

So when I discussed the possibility of leaving graduate school to start a job as a tenure-track professor with my advisors, it was with trepidation. The plan was to finish my dissertation and defend that fall, anyway, but working full-time in a new job as an academic while finishing the project seemed like a bit much. Wouldn’t it be safer to stick around, wrap things up, and let “the real world” hold off for a year? My advisors politely, and rightly, disagreed, gently kicking me out of the nest.

I moved late that summer, just a few days before the start of the fall semester. And the combination of starting a job I didn’t feel like I deserved, both because I hadn’t yet completed my doctorate and because I’d been offered a job that hadn’t required the stress-inducing application and hiring process I knew my peers had or would struggle through, should have brought back my imposter syndrome in force. It didn’t. Thankfully, completing a dissertation while working full-time leaves one less time to overthink things, and I graduated the following May. And while I wish this were a victory narrative, that’s hardly the case.

There were no anime lines to demonstrate that I’d powered up beyond such self-doubt, no freeze-frame as I triumphantly pumped a fist in the air holding my diploma as proof that I did, in fact, belong after all. Sadly, it doesn’t work like that, as much as I like to imagine taking over as coordinator and hiring a new staff was like my own personal team-building montage set to an upbeat 80s pop song. If anything, the imposter syndrome isn’t even different now. I’m still struck with moments of self-doubt: that I tricked my way into my job, that my colleagues who were once my professors are giving one another knowing glances when I speak up in department meetings. The difference is that I’m better at recognizing those moments of self-doubt through mindfulness, spotting them trying to sneak in, and non-judgmentally confronting them. I also know that to do this I need to take care of myself; if I don’t get enough sleep, food, or exercise, the moments last longer. I write strictly for the purpose of checking in with myself, of being mindful. And I’m back in therapy.

Unsurprisingly, when I was asked to submit this chapter, the imposter syndrome hit me like a dodge ball to the gut. When I initially read about the call for papers on this topic, it was so near the deadline that I gave it little thought beyond, “I’ve been working on something like that,” before submitting. As such, in many ways, writing this has been one of the more difficult tasks of my academic career thus far. I originally proposed it as a Tutor Column, but the editors asked me to expand it into a chapter for this digital edited collection. The task was daunting, if only because what was initially conceived as a 1500-word reflection on the practice of tutoring as validating was now intended—as part of an edited collection—to be more than four times that length, requiring more research and much more introspection. And while the words themselves flowed fairly easily, returning to the work has been panic-inducing.

Receiving the e-mail from the editor a few months after submission (and again with each round of review) felt like the bill had come due, like I was finally going to pay for my crimes against the academy — premeditated perjury of qualifications. Perhaps it hit me so strongly because I was expecting it. I was about half-way through my first year as a tenure-track faculty member with my doctorate in hand (no longer ABD), and I felt like I was just waiting to be found out.

I thought:

“Am I representing this feeling accurately?”

“Is that what really happened or just what I remember?”

“What if my privilege as a male academic renders my experiences as a Chicano academic meaningless?”

“So many people definitely have it way worse than me! What if they think I’m appropriating their imposter syndrome for my own gain? Am I?!”

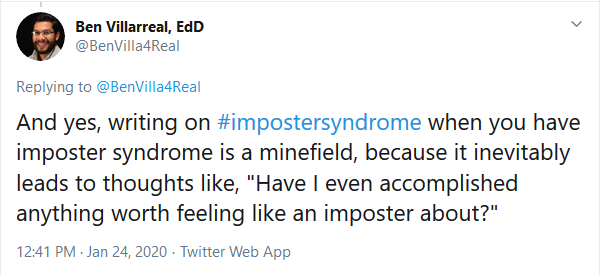

And even if I can often answer these questions for myself (some just by returning to the methods of autoethnography), there’s the inevitable “What if I don’t even have imposter syndrome, and I’m just vaguely unconfident in my accomplishments?” This, too, can spiral quickly into “Have I even accomplished anything worth feeling like an imposter about?” (@BenVilla4Real)

On the days these thoughts have gotten the better of me, at best I’ve not been able to even look at this chapter, and at worst, I’ve strongly considered just pulling it, writing the editors and saying, “Thank you but I’ve decided not to publish at this time.” But the thought of having to write that email is enough to stop me from doing it.

Thankfully, when these feelings started to resurface at the beginning of another academic year (August, again), I recognized the sense of anxiety that came with them and got myself back into therapy, which I had left when I moved and put off because I felt pretty well-adjusted. (Just writing that now makes me roll my eyes.)

Over the next few months, I started unpacking my imposter syndrome, realizing it was a source of a lot of my anxiety and not just another way my anxiety manifested like I had assumed. Further, while some of my imposter syndrome could be seen as class-related (and I’m sure it is), just as much, if not more, is likely rooted in my Chicano-identity. I see this more concretely in light of Cokley et al.’s research. But that journey of realization could be its own autoethnography.

So when my gut told me to politely but immediately decline the offer to submit this chapter, I was able to hold that thought and take it to my therapist, who promptly suggested I check out Brené Brown’s The Gifts of Imperfection. My therapist suggested that my imposter syndrome in this instance was urging me to decline because of my fear of making myself vulnerable. Sharing this story might be helpful, might connect me to others who can relate — meaning I’m not an imposter but one of many who feel this way.

Reading Brown’s work has helped me write this, so much so, I wish I had discovered her sooner. Much of what Brown writes about relates directly to imposter syndrome, and her chapter on perfectionism is very relatable and helped me remember that as I write my autoethnography I’m writing to no one’s experience but my own and that doing so authentically requires I acknowledge that I’m not perfect. Trying to pretend otherwise is where imposter syndrome starts to grow (56-57).

In their book, The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy, Maggie Berg and Barbara K. Seeber adapt Brown’s ideas into a definition of academic shame:

Academic shame is the intensely painful feeling or experience of believing that we aren’t as smart or capable as our colleagues, that our scholarship and teaching isn’t as good as that of our colleagues, that our comments in a meeting or at a speaker event aren’t as rigorous as that of our colleagues, and therefore we are unworthy of belonging to the community of great minds. (87)

Neither Berg and Seeber or Brown refer to this as “imposter syndrome,” but its roots are the same — the fear that one is not enough.

Brown argues that mindfulness is key in managing this kind of perfectionism (60), something I felt woefully unpracticed in. But now I realize I did take time for this during my doctorate, and these memories echoed back to me: I had a yoga instructor who included short meditation into their practice; a mentoring teacher who began our class with “Writing for Full Presence” (C. Brown) and who gave us a chance to gather our thoughts and emotions before jumping into discussion of the material; and most importantly, my work in the GSWC, in which my constant affirmations that a writer’s work was never perfect but always in progress, and that that was okay. And now, those bookmark tips do kind of help: the breathing helps when I notice my shortened breaths, and listing recent accomplishments keeps me from feeling like I haven’t occupied my time.

The point of sharing this is to show that facing imposter syndrome, like all mental health (and all health, really), is an ongoing process. Mine did not go away when I graduated, just as working in the GSWC didn’t take it all away. But working there mindfully and supporting others with many of the same doubts was a start in my own support system, even if, for better or worse, I didn’t realize it at the time. This is not to say that working at a writing center will help everyone (or even that working at my writing center helped everyone), only that it helped me, so much so that I cannot imagine having completed my doctorate without it.

Near the completion of the first draft of this chapter, I was asked to again step in to run a writing center, this time, the first one ever where I worked. I felt confident and qualified to do so, more so than when I took over at the GSWC, perhaps because of this work. Without interrogating my choices as coordinator here, I might have gone into that new center determined to recreate the GSWC — ill-advised not just because of what I have learned since then (both about myself and writing center administration) but because of differences in who I am trying to serve. At the GSWC, I tried to make it a space for the tutors I worked alongside, reconciling what I had needed as a tutor with what they were telling or showing me they needed; it would have been wrong to simply take that and expect the new tutors I managed and trained to need or even want the same things. For that reason, I’m glad this chapter evolved beyond the scope of my initial plans — to simply reflect on the ways that helping graduate writers with their writing affirmed that I belonged there among them. Reflecting on how tutoring as a mindful practice led to my sense of belonging has given me a model for trying to make sure other graduate student tutors feel like they belong, as well.

Imposter syndrome, along with other mental health concerns, will likely continue to prevail in academia, and reflecting on my own has, I think, given me a new way of understanding these concerns. Further, sharing my experience — as difficult as writing this has been — is necessary in breaking down barriers that serve as the foundation for such self-doubt; while research like that done by Degner et al. is indeed necessary, so are individual stories that “encourage compassion and promote dialogue” (Ellis and Bochner 748). My hope is that this chapter accomplishes that in some small degree, so that we might all see writing centers as places of mindfulness for those who visit and work there.

Works Cited

@BenVilla4Real (Benjamin J. Villarreal). “And yes, writing on #impostersyndrome when you have imposter syndrome is a minefield…” Twitter, 24 Jan. 2020. https://twitter.com/BenVilla4Real/status/1220793750751858688?s=20

Berg, Maggie, and Barbara K. Seeber. The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy. U of Toronto P, 2016.

Brown, Brené. The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You’re Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are. Hazelden, 2010.

—. “The Power of Vulnerability.” TED Talks, June 2010. https://www.ted.com/talks/brene_brown_the_power_of_vulnerability

Brown, Courtney. “Write to Learn: The Power of Personal Writing.” CPET, 15 August 2020. https://cpet.tc.columbia.edu/news-press/write-to-learn-the-power-of-personal-writing

Clance, Pauline Rose, and Suzanne Ament Imes. “The Imposter Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention.” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, vol. 15, no. 3, 1978, pp. 241-247. APA PsycArticles, doi:10.1037/h0086006.

Cokley, Kevin, et al. “An Examination of the Impact of Minority Status Stress and Impostor Feelings on the Mental Health of Diverse Ethnic Minority College Students.” Journal of Multicultural Counseling & Development, vol. 41, no. 2, Apr. 2013, pp. 82–95. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2013.00029.x.

Cope-Watson, Georgann, and Andrea Smith Betts. “Confronting Otherness: An E-Conversation Between Doctoral Students Living with the Imposter Syndrome.” Canadian Journal for New Scholars in Education/Revue canadienne des jeunes chercheures et chercheurs en education, vol. 3, no. 1, June 2010, pp. 1-13. https://cdm.ucalgary.ca/index.php/cjnse/article/view/30474

Cox, Elizabeth. “What is imposter syndrome and how can you combat it?” TED Talks, August 2018. https://www.ted.com/talks/elizabeth_cox_what_is_imposter_syndrome_and_how_can_you_combat_it

Degner, Hillary, et. al. “Opening Closed Doors: A Rationale For Creating A Safe Space For Tutors Struggling With Mental Health Concerns of Illnesses.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2015. http://www.praxisuwc.com/degner-et-al-131/

Ellis, Carolyn, and Arthur P. Bochner. “Autoethnography, Personal Narrative, Reflexivity: Researcher as Subject.” The Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed., edited by N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln, Sage, 2000, pp. 733-68.

Eskridge, Don. The Resistance. 2009. http://indieboardsandcards.com/index.php/our-games/the-resistance/

Featherstone, Jared, et al. “The Mindful Tutor.” How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019. https://wlnjournal.org/digitaleditedcollection1/Featherstoneetal.html

Inman, James A. “Designing Multiliteracy Centers: A Zoning Approach.” Mulitliteracy Centers: Writing Center Work, New Media, and Multimodal Rhetoric, edited by David M. Sheridan and James A. Inman, Hampton Press, 2010, pp. 19-32.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. “Jon Kabat-Zinn: Defining Mindfulness.” Mindful.org, 11 January 2017. http://www.mindful.org/jon-kabat-zinn-defining-mindfulness/

McKinney, Jackie Grutsch. Peripheral Visions for Writing Centers. UP of Colorado, 2013.

Revuluri, Sindhumathi. “How to Overcome Impostor Syndrome.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 4 Oct. 2018. https://www.chronicle.com/article/How-to-Overcome-Impostor/244700